Understanding carbon offsets: between criteria and challenges

· 7 min read

This article is part of illuminem's Carbon Academy, the ultimate free and comprehensive guide on key carbon concepts

Carbon offsets are crucial elements of the carbon market. They provide a company or organization with the opportunity to compensate for their carbon emissions, allowing them to invest in projects that reduce or remove an equivalent amount of CO2 from the air. Emissions produced in one place can thus be balanced out by carbon reduction or removal activities somewhere else. Investing in these projects enables companies to obtain carbon credits, each one of which represents one metric ton of CO2 that has been either avoided or removed from the atmosphere.

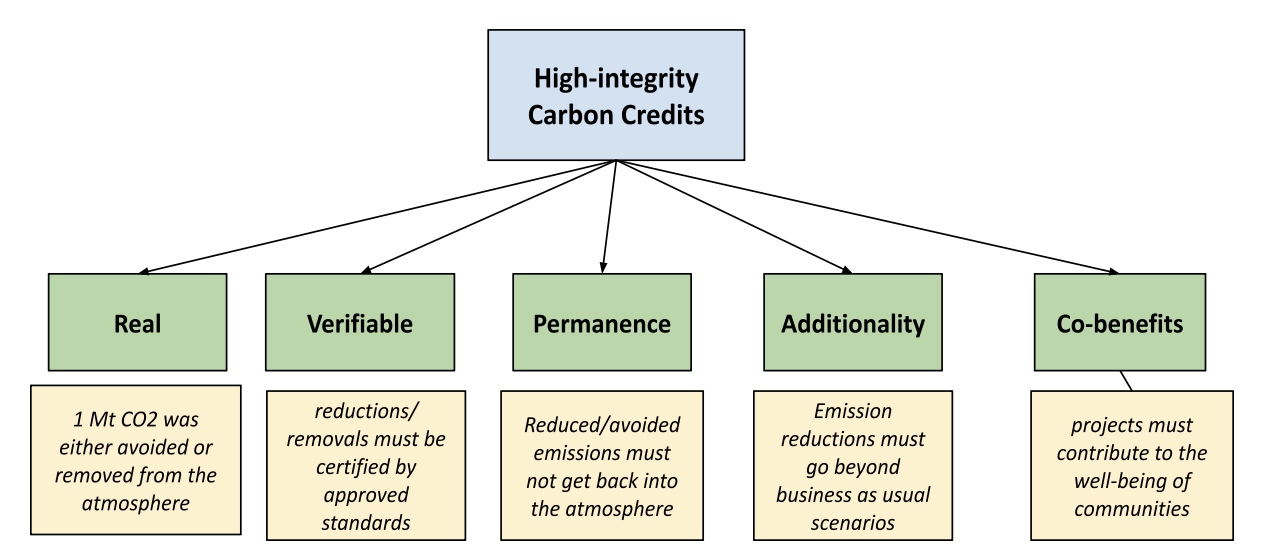

Investing in the right carbon offset project is not without its challenges, with the main one being the selection of high-integrity carbon projects. In the following section, we explore the key principles that should guide the selection of high-quality carbon credits.

There are 5 main criteria to consider when buying carbon credits:

Implementing all these parameters is easier said than done. Each individual project comes with a specific set of problems and considerations. For example, gauging CO2 emission reduction/removal in nature-based projects proves considerably more difficult than in a renewable energy project: while in the former, offsets have to be quantified across a highly diverse and diffuse landscape, in the latter they can be measured from a single source emission point, such as a wind farm. Challenges also extend to project oversight: a forestry project is more difficult to maintain than it is a wind farm, since trees can be destroyed by pests and fire, or be subject to other weather conditions. On the other hand, although these considerations may indicate that nature-based projects pose greater challenges, they nevertheless provide a distinctive advantage through their robust impact on sustainable development.

Time makes it even more difficult to put the above-mentioned criteria in practice. For instance, projects that were once considered additional may no longer be so after a certain period. Furthermore, verifying additionality can prove challenging since it presupposes the ability to directly observe the counterfactual world in which the offsetting activity was not performed.

The challenges associated with carbon credit criteria also revolve around the entities responsible for issuing and verifying these credits. Currently, major players in this spectrum include well-known agencies such as GoldStandard and Verra. However, relying solely on credits verified by these agencies does not always reflect on the quality of the credits being purchased. The market experienced a wave of media backlash, with an investigation by The Guardian suggesting that a significant portion of carbon credits issued by Verra could be 'phantom credits' (for an alternative perspective on The Guardian’s article check here). While this is not to be underestimated, we should stress that this was more of a systemic problem, particularly associated with faulty baselining practices within forestry projects. At any rate, the risk that the issuance of worthless credits may extend beyond a single case can potentially set in motion a vicious circle, whereby the acquisition of erroneous credits leads to reputational challenges for both issuers and buyers.

A commercial conflict also runs through the standards-setting landscape. Standards bodies primarily generate revenue through issuance fees, receiving a fraction for each carbon credit they issue. Consequently, there is an inherent incentive to set lower standards in order to encourage a higher influx of credits and increase revenues. The lack of clear directives on where to set these standards poses a significant risk in this regard. This risk is particularly pronounced in the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM), as opposed to the Compliance Carbon Market (CCM), where the absence of a central regulatory authority contributes to a more decentralized and dynamic ecosystem of intermediaries.

These considerations highlight some of the flaws within carbon markets, underscoring the substantial room for improvement in achieving more effective solutions. Despite these flaws, carbon credits stand out as one of the most effective measures to accelerate climate action: not only do they provide the only market-based solution to emission reductions, but also represent the only existing system that prevents polluters from continuing to emit at no cost. Furthermore, it stands as the only system in place today that is able to scale up CDR technologies at a reasonable rate. The focus should thus not be on discarding carbon credits as such but rather on enhancing the use we make of them.

In this regard, a few key solutions emerge as particularly desirable towards enhancing the Carbon Market, especially the Voluntary Carbon Market:

By implementing these solutions, the VCM can create a resilient framework for assessing the credibility of carbon offset projects, instilling confidence in stakeholders and aligning its practices more closely with established market standards.

This brief article has outlined the essential criteria for evaluating carbon credits before making a purchase. It has also shed light on some of the flaws within carbon markets (with emphasis on the VCM), such as the absence of clear and consistent standards and the lack of incentives and regulations, emphasizing the need for future measures. Despite these challenges, carbon credits remain powerful tools to tackle climate change, and their purchase can significantly contribute to broader sustainability efforts.

Are you a sustainability professional? Please subscribe to our weekly CSO Newsletter and Carbon Newsletter

illuminem briefings

Architecture · Carbon Capture & Storage

illuminem briefings

Carbon Market · Public Governance

illuminem briefings

Carbon · Environmental Sustainability

Inside Climate News

Carbon · Public Governance

Interesting Engineering

Carbon Capture & Storage · Architecture

Carbon Herald

Carbon Capture & Storage · Maritime