illuminem guide to the Compliance Carbon Market (CCM)

· 9 min read

This article is part of illuminem's Carbon Academy, the ultimate free and comprehensive guide on key carbon concepts

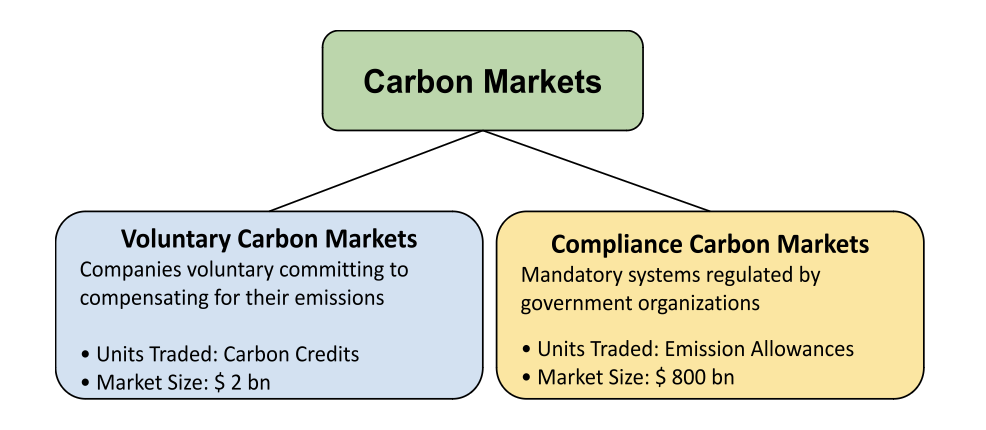

The Carbon Market consists of two primary segments: Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) and Compliance Carbon Market (CCM). We dealt with Voluntary Carbon markets here. In this article, we dive deeper into the CCM, dividing our discussion into 6 distinct sections:

There are at least four main differences between the VCM and the CCM

The infographic below helps visualize all these points:

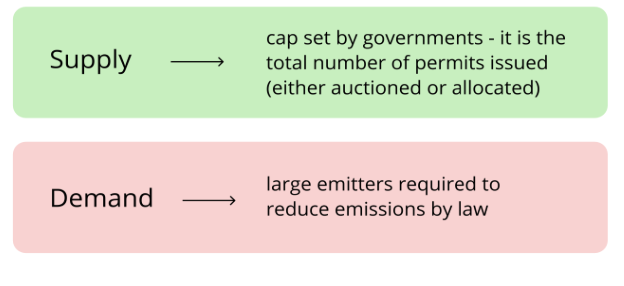

As shown in the infographic below, most Compliance Markets work on a cap-and-trade basis:

The governmental body identifies specific sectors characterized by high carbon intensity and substantial CO2 emissions. It establishes a cap on the overall permissible emissions, which is the maximum amount of greenhouse gasses that can be released by all covered entities. A cap or limit is set on the total amount of specific greenhouse gasses that can be emitted.

Industries covered by the cap can take two approaches to comply:

They can implement measures within their own operations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions directly from their activities. This could involve adopting cleaner technologies, improving energy efficiency, modifying production processes, or utilizing renewable energy sources.

They can buy carbon emission allowances/permits

Permits are distributed among these covered entities, representing the right to emit a certain amount of greenhouse gasses. An EU Allowance, for instance, grants the right to emit 1 ton of carbon dioxide during a specified period.

The government issues a limited number of emission allowances in accordance with this cap. The total number of allowances allocated is designed to decrease in a way that allows carbon price to go up, and incentivize alternative decarbonization measures. Whilst in the first year the government body will issue a given amount of allowances, in the second year it will reduce its number. An entity must surrender enough allowances to cover its emissions production on a yearly basis, otherwise fines are imposed. Companies can buy and sell allowances from – and to – each other. They can trade surplus or deficit of carbon allowances up to total cap every year. If a company has 50 units and emits 100, it has the option to acquire buy units or allowances from companies that have achieved faster reductions and possess a surplus. In this sense, buying carbon allowances is a way for entities under the scheme to exceed their own carbon budget. If an entity reduces its emissions, it can keep the spare allowances to cover its future needs or sell them to another party that is short of allowances.

Established in 2005, the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) is the main Compliance Carbon Market globally. It regulates around 11 thousand installations across different sectors from heat and power generation to energy intensive industry sectors, and stands as the largest cap-and-trade program, addressing more than 40% of the European Union's greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as of 2020. The cap undergoes an annual reduction of 2% and the current cost per tonne of CO2 is around 80 euros. The graph below shows the cap’s annual decrease and illustrates the proportion of allowances that are either given for free or auctioned (see also below on this point):

Other Compliance Markets include:

Understanding how agents can engage in this market involves explaining how allowances are allocated to them. There are two options for emissions allowance distribution:

Organically, the CCM, like every market, has:

Let’s go through these aspects separately.

While in the Voluntary Carbon Market demand is free and unregulated, in the CCM it is constrained by law. The infographic below illustrates the actors and components making up supply and demand:

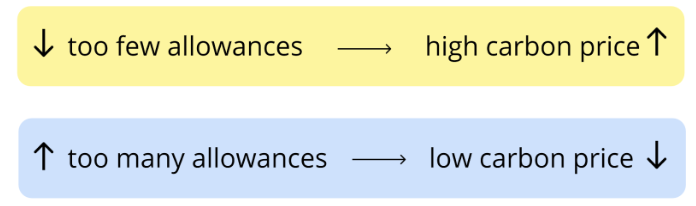

The actual price is determined by the number of allowances on the market:

Ideally, prices should go up but the aim is to strike a balance between too low and too high prices.

Indeed, IF

The CCM is not exempt from problems. Here's a breakdown of the challenges that the CCM faces in achieving its full potential:

Carbon leakage refers to the situation where businesses move their production to regions with less stringent environmental regulations or lower carbon prices. By doing that, they can avoid paying for their carbon emissions.

The Carbon Border Adjustment (CBA) is a policy tool designed to address concerns related to carbon leakage and the competitiveness of domestic industries in the face of varying carbon prices between different regions or countries. The concept involves imposing a charge on the carbon content of imported goods to ensure that they face a similar carbon cost as domestically produced goods, thereby preventing companies from relocating production to regions with lower environmental standards. A CBA is designed to prevent a competitive disadvantage for domestic industries that are subject to carbon pricing mechanisms by ensuring that imported goods face a similar carbon cost.

There has been an issue of oversupply of allowances in the CCM, which has led to low prices. There are two main reasons behind this oversupply: low penalties and unambitious cap

Low Penalties: The reduced demand for permits stems from the fact that covered entities may not face significant economic penalties for exceeding the cap. The cost of failing to comply with the CAP limit is relatively inexpensive (as low as 100 Euros per excess ton of C02 produced over the cap).

Unambitious Cap: Oversupply can build up if the emissions cap is unambitious. If, collectively, the covered entities emit less than the total cap allows, there is an oversupply of permits in the market. If compliance with the cap is easily achievable through internal measures, the economic incentive to purchase additional permits diminishes. In other words, covered entities prioritize cost-effective internal strategies rather than incurring expenses to buy permits. These measures can involve operational efficiencies, lower energy consumption, and overall reduced carbon intensity.

A high cap implies that covered entities have more flexibility and may not face significant challenges in meeting the cap through internal emission reductions. With a less stringent cap, there may be limited economic incentives for covered entities to invest in expensive emission reduction measures.

As a result, they may not actively seek additional permits in the market because they can meet their emission targets without the need for external allowances.

With more permits available than needed, the market price for permits tends to decrease. This makes permits more affordable for those entities that may still choose to buy them rather than relying solely on internal emission reduction measures.

The EU adopted two solutions:

Compliance Carbon Markets (CCM) present a mixed bag of advantages and disadvantages. Two main flaws stand out within these markets: the oversupply of emission allowance and the impossibility of investing in carbon removal technologies. On the positive side, buying and surrendering allowances in a cap-and-trade system provides an alternative to using carbon offset credits for claiming emission reductions. This approach does not incur quality issues often shown in the Voluntary Carbon Market, like the absence of additionality.

A convergence between Voluntary and Compliance Carbon Markets might help address the CCM limitations, opening its doors to carbon removal projects. Carbon markets are becoming increasingly interlinked, especially as governments promote increasing participation in Voluntary Markets. This integration of market frameworks holds promise for bolstering efficiency, credibility, and liquidity.

In conclusion, Compliance Carbon Markets (CCM) offer a robust mechanism to mitigate climate change by providing structured frameworks for emission reduction efforts. This dynamic drives up the price of carbon allowances, effectively internalizing the social cost of carbon and making it less economically advantageous to pollute.

Are you a sustainability professional? Please subscribe to our weekly CSO Newsletter and Carbon Newsletter

Glen Jordan

Sustainable Lifestyle · Sustainable Living

illuminem briefings

Architecture · Carbon Capture & Storage

illuminem briefings

Labor Rights · Climate Change

Financial Times

Carbon Market · Public Governance

GB News

Carbon · Sustainable Mobility

The Independent

Effects · Climate Change