· 13 min read

We may all be made of stars, but that doesn’t mean we all spread light in the darkness when it comes to effective and economically viable climate solutions. Kahneman’s Nobel-prize winning work in cognitive science along with many others, captured in Kahneman’s excellent book Thinking, Fast and Slow, helps us understand our own biases to a certain extent, and helps us spot others’ biases more easily.

Policy makers, decision makers and influencers on the core climate action file, where we will be investing trillions in transformation in the coming years and decades, need to have clearer eyes than the average person on the street. They need to work harder to understand their own biases and blind spots, and also ensure that they work with teams and advisors who have different biases and blind spots to ensure that groupthink doesn’t lead them down an unfortunate path.

The things we do and don’t know and the things we refuse to know are top of mind for me as I look through a glass darkly into the future, trying to articulate where aviation, marine shipping, hydrogen and the like will go. I see clear evidence of cognitive biases in multiple fields among senior and influential people.

And, of course, I’m subject to biases as well. This is not just about other people, but about my failings as well. For example, I live in one of the most densely populated area codes in North America, perhaps the most densely populated. Sixteen condo buildings of twenty or more stories are visible from my home office window. British Columbia has the highest penetration of electric vehicles of any state or province in North America. Bike share is everywhere. The two primary car shares have hybrid-electric and now fully electric cars with Zerocar’s new Tesla Model 3 service. Vancouver’s transit is second only to Singapore’s of the places I’ve lived, and the Skytrain continues to have by far the best views of any light rail system in the world. I’ve driven perhaps once in the past year, walking everywhere, using bikeshare regularly and occasionally taking transit.

When I write about vehicle-to-grid and vehicle-to-home technologies, my starting assumption is multi-unit residential buildings in denser urban areas, not detached suburban homes. That’s a more useful frame, as even in the suburban sprawl of the US, 20% of the inhabitants live in multi-unit residential buildings. In Asia, it’s 90%, and there are a lot more people in Asia. I am accidentally an outlier among North American transformation strategists, which means my biases are more aligned with the conditions in the rest of the world. By contrast, many of the people I interact with are affluent people, often thought leaders, who have 2- or 3-car garages with EVs parked in them and solar panels on their roof tops, and who start with the assumption of detached homes and hence consider V2H and V2G as obvious choices, even if they would likely never agree to vehicle-to-grid arrangements because they would pay vastly less.

For a clearer external frame on this, only 0.8% of the world’s population lives in detached homes in America’s sprawling suburbs. Frequently it seems like much more as those detached homes get far too much airtime both in popular media and in climate solution circles.

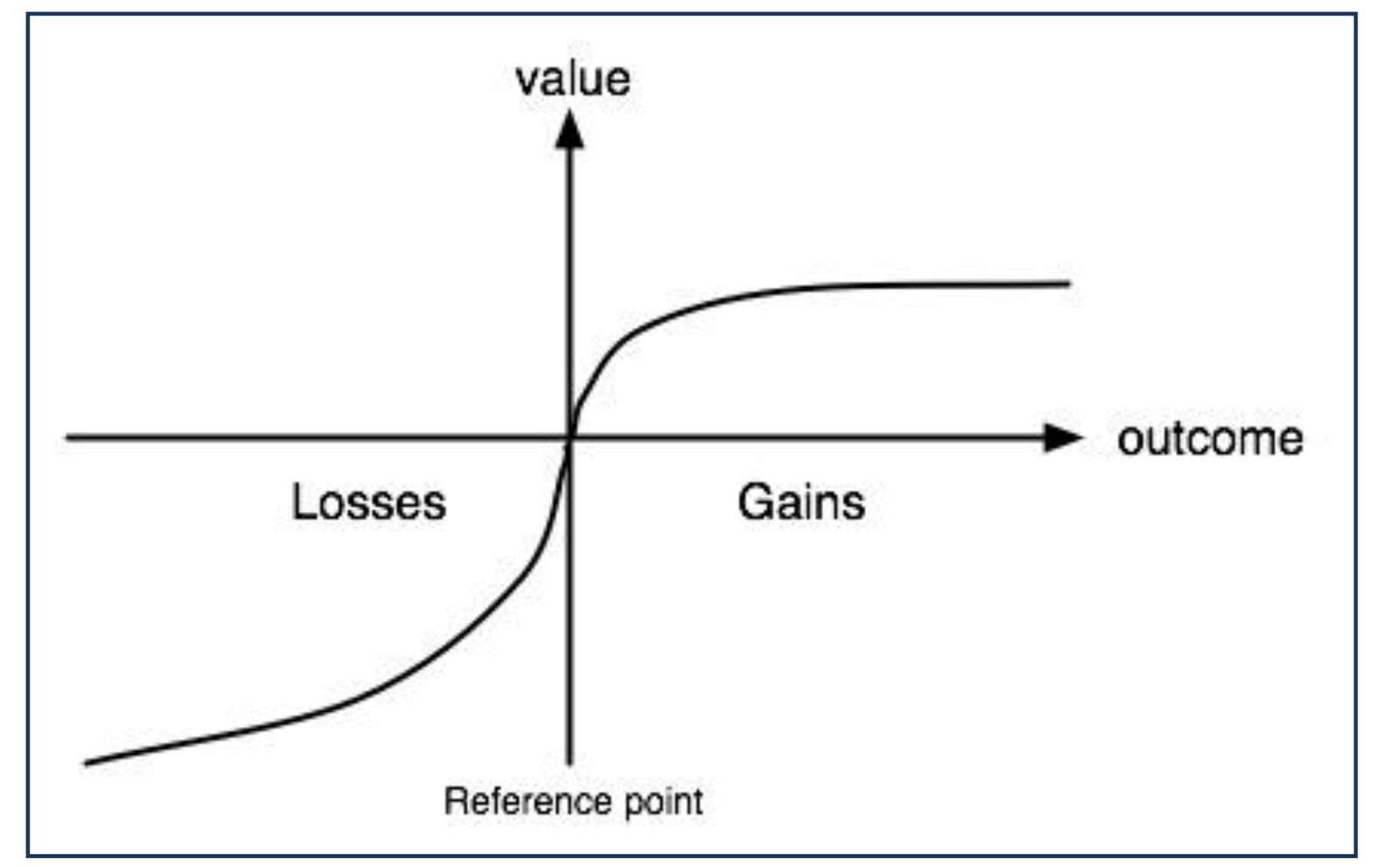

One of the other biases vehicle-to-grid advocates often get wrong is Kahneman’s prospect theory, for which he won the Nobel Prize.

Cognitively, humans fear loss much more than they value gain. For vehicle-to-grid, that means that they fear loss of range and loss of the money that is sunk into charging their vehicle more than they value the potential money that they might earn from a utility. This discontinuity would mean that utilities would have to pay much more to the vehicle owners than the electricity is worth to overcome the loss aversion. An 80 kWh EV that sells 10 kWh back to the grid at $0.30 per kWh would make less than the price of a good cup of coffee, making the economic transaction and required hardware and handshakes bafflingly unlikely. The odds of detached home owners valuing three-quarters of a cup of coffee more than potential range loss are very low. It’s an interesting technology, but it runs into a brick wall of human nature. Vehicle-to-home is more likely, but once again it’s vastly overstated as a value proposition by many simply because they live in detached homes and as a result think it’s much more common than it is. Advocates assert that utilities will pay many dollars per kWh in the most demanding periods, but that still equates to only dozens or a couple of hundred dollars per year, insufficient to overcome loss aversion for most people unless they don’t get the choice and are automatically opted in.

And people in the US have 3 other biases which come clearly through when I speak to them and read what they write and publish. First, the US has the least reliable grid among developed countries, with over 4 hours of outages per customer per year on average, compared to under 15 minutes per year in Germany and Denmark. Second, many American electrical utilities are among the most grasping and greedy, and among the ones with the worst customer service in the world. Third, Americans have a dysfunctional myth of rugged individualism. This leads many of them to assume that taking a suburban home completely off-grid, or at least loading it up with expensive storage, makes rational sense, and that the desire to do so is common. It isn’t economically rational, isn’t an effective climate change strategy, and globally this perspective is deeply unusual. There are aspects of the availability bias here, the cognitive bias where what easily springs to mind is assumed to be much more statistically common than it really is.

When I write about building integrated solar panels, especially the nonsensical and recurrent idea of solar windows, it’s in context of vast global urbanization, with urban windows that are not remotely aligned to the sun but to the street grid, windows which are frequently in shade from other buildings, and large building energy requirements that can’t even begin to be met from deeply inefficient, poorly aligned, shaded, transparent solar panels. Of course, there are lots of windows in suburban sprawl in the US, but the suburbs are mostly low-rises with fewer windows, and as noted, suburban US buildings are a tiny fraction of global building stock.

When I talk with thought leaders such as Mark Z. Jacobson or Bill Nussey, both stronger advocates of distributed solar than I am, or in Nussey’s case provide feedback on a late draft of his book, Freeing Energy, I’m doing it in context of massive and dense urbanization and the much denser urban patterns that exist around the world than they are used to. Like many Americans, they live in detached homes, and of course both have solar panels on their large roofs. It’s very easy for them to think, unless they engage Kahneman’s system two slow thinking and look at external data, as both do, that rooftop solar will be much more dominant than it can be. This doesn’t make their work problematic, but it can skew it, especially their initial thinking on subjects. However, I’m just as subject to undervaluing rooftop solar because the examples immediately available to me — high-density, low-insolation Vancouver — don’t make it a reasonable choice.

While I’m a strong advocate of electric vehicles, I’m also someone who has been carless — this time — for a decade, and during that time lived in Toronto, São Paulo, Singapore, Calgary, and Vancouver, cities with vastly different patterns of urbanization and sprawl. I’ve lived with the downsides of being carless in the deeply car-centric city of Calgary, and the downsides of owning and driving a car in Toronto’s rush hour and around downtown in general. I’ve had a single day which would make an urban transit nerd glow with happiness, taking six separate modes of transportation, from bike share to subways to car shares to walking on different legs of my journey. As such, I’m struck by the naiveté of people at both ends of the spectrum, the ones who think everyone will go car free, and the ones who think electric cars are far more of a climate solution than they are.

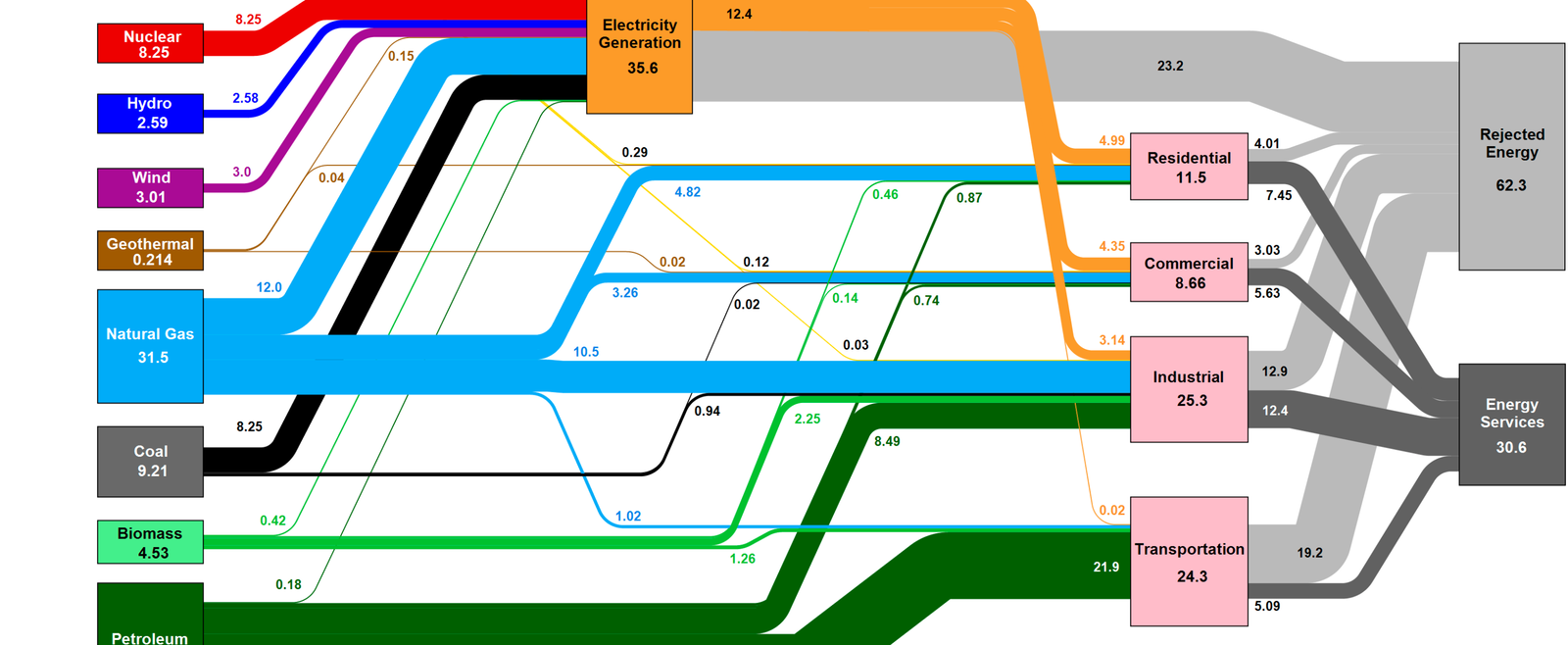

A number of people who should know better seem to be unaware that our society throws away two-thirds of primary energy, people including Vaclav Smil it seems, who recently published another book and was interviewed on his deeply and inaccurately pessimistic book by New York Times Magazine. I assessed Smil’s take on renewables, and when there was zero mention of rejected energy or the much greater efficiency of all electrified energy services provided with renewable electricity, went looking for any reference in any of his works to it. Nothing. Nada. Zip. This is one of 3 major gaps for Smil, so his perspectives should be taken with a grain of salt.

I constantly run into people in discussions — investors, VCs, technologists, economists — who are dealing with the transformation to a low-carbon future who don’t know this. My Short List of Climate Actions That Will Work gets attacked regularly because I exclude efficiency as a top line item. Electrifying everything and using renewable electricity comes with a 50% efficiency bonus, vastly more than any other efficiency gains possible. This seems obvious to me because I’ve internalized this perspective, but Smil and others are still living in a world where all the energy in primary energy sources has to be replaced. As I wrote a couple of years ago, building efficiency is overrated and more of an economic concern, and we should be looking at embodied carbon much more seriously. This doesn’t mean efficiency in existing buildings doesn’t have a part to play, but low-hanging fruit insulation typically suffices, and heat pumps add much more climate value.

Similarly, grid storage is a major topic these days, and I speak to energy experts globally pretty much every week these days. And yet virtually all of them are unaware that pumped hydro storage is by far the largest source of grid storage today, that it’s by far the biggest under-construction storage technology today, that China is building far more pumped hydro than any other country in the world, that it’s not an environmental problem, that it doesn’t take much water, that there are 100 times the resource in convenient locations as is required globally, and that it is a 100+ year infrastructure asset. This includes major energy investors with billions to spend, and who need to be guided to spend that money wisely. Thankfully, I’m now speaking to investor groups with hundreds of millions to hundreds of billions to invest around the world fairly regularly, so I am assisting the right people to overcome this blind spot. (A major pumped hydro development win is still under wraps pending more negotiations, so watch this space).

Similarly to urban sprawl, Americans assume that the rest of the world’s regulatory structure for hydro is as dysfunctional as theirs, so it can’t be easily built anywhere else either. As such, they are making investment decisions in the absence of critical knowledge. That doesn’t, by the way, mean that they would make substantially different decisions, but that they are operating in ignorance of data which would shape their choices, and hence are making sub-optimal ones.

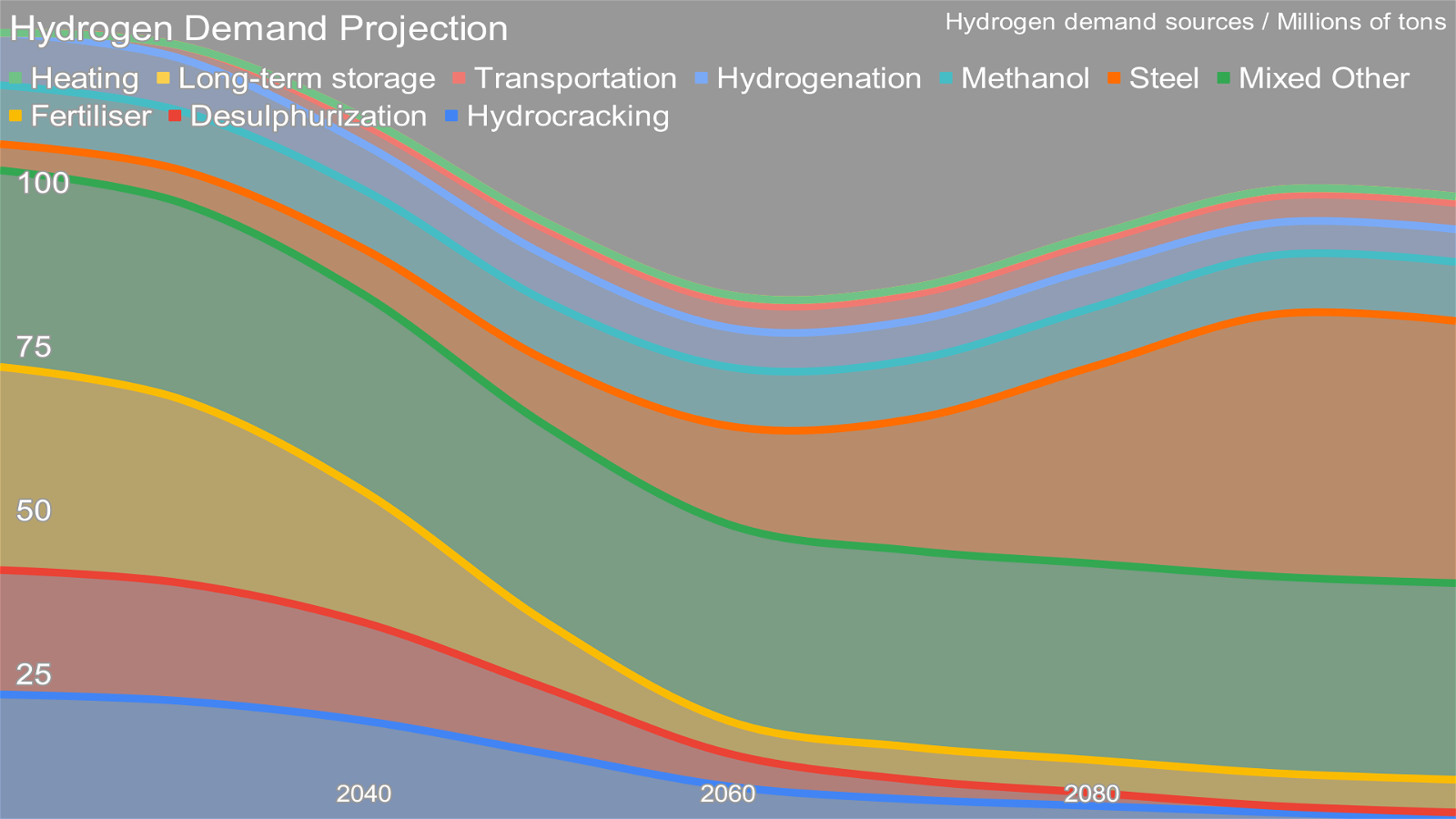

When I speak to Paul Martin, a chemical processing engineer with 30+ years of hydrogen experience, and a founder of the Hydrogen Science Coalition, he refers to people having ‘burner boxes’ on their heads. This refers to people who work with liquid or gaseous fuels today who are stuck inside the paradigm of burning things for heat. This could be natural gas generation utilities, or industrial concerns, or transportation policy makers and analysts. But their bias due to long familiarity is that the only energy that counts is energy that you light a match to. This is a deeply false proposition, and one that’s very damaging to useful discourse.

That’s shaping the thinking of governments and corporations around hydrogen right now, as a pervasive belief is that natural gas, diesel, Jet A-1, and other fuels must be replaced by something that burns, and hydrogen is the only clean-ish candidate. The EU’s energy policies are leaning on hydrogen in the absence of any particularly rational reason for this. I’ve recently published a report on the skewed energy policies that Europe and European corporations are promoting in northern Africa, and the biases are clear.

Certainly when it comes to hydrogen, there are people who became pot-committed to hydrogen for road transportation sometime in the past couple of decades, and just can’t let it go. Whether they work for Ballard, or just think fuel cell vehicles are neat, their biases shine through when you speak to them. They just can’t accept that hydrogen is inefficient, ineffective, and expensive. I’m sure that I’ll have the usual suspects and more chiming in with comments on this article. Their confirmation bias — Kahneman writes of this in Thinking, Fast and Slow of course, and I’ve spoken to cognitive scientists like John Cook, famous for Skeptical Science and Cranky Uncle vs Climate Change about it — prevents their acceptance of data which contradicts their preconceptions, and means that they vastly over rely on weak data that supports their preconceptions.

Similar to hydrogen fuel cell advocates are those who see nuclear energy as a much bigger solution, or perhaps even the only viable solution, to decarbonizing energy. As I’ve written before about people like Bill Gates and Michael Shellenberger, they reached this pro-nuclear conclusion in the early to mid 2000s, when it was truly uncertain whether wind and solar could scale, be reliable on grids and be cost effective. They haven’t updated their priors on the subject. As a result, they ignore — in Shellenberger’s case actively and intentionally — empirical reality from the past dozen years that show clearly that nuclear is, at best, something which might be useful for the last 5% to 20% of electrical generation, not 50% to 80%. Many people are holding onto perspectives that they reached often decades ago, and for a variety of reasons are not updating their data sets and analyses.

Finally, for at least this brief listing, is the odd perspective that countries can get fossil fuels from anywhere, but that electricity is difficult to trade across borders and risky. HVDC and other transmission is not conceptually or economically different than pipelines except that it’s vastly cheaper to move electrons than to push molecules. Electricity is just energy, and no harder to hedge than fossil fuels, and renewables just generate electricity that can be moved across continent+ scale grids. Yet for some reason people keep telling me that electricity transmission across borders is too risky and difficult to hedge, despite events like the natural gas freezing failures in Texas in February of 2021, the massive natural gas price volatility that crippled Europe in the winter, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and Fukushima’s disruption of nuclear generation globally. We can trade eggs, grain, coal, steel, iPhones, and everything else across borders without concern, but electricity transmission is somehow a step too far.

My awareness of the blindspots and biases in others does not prevent me from having my own cognitive lapses. However, I work hard to overcome them. I engage system two thinking by digging into the underlying numbers and doing calculations personally, and I find external perspectives and data to extend and challenge my thinking. And, of course, as I publish regularly, people challenge my blindspots and biases constantly, something for which I’m grateful.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.