What does Bill Gates’ favorite energy guru, Vaclav Smil, get wrong?

· 10 min read

A few days after Earth Day this year, my fellow Canadian Vaclav Smil had an extended interview published in the New York Times Magazine about him, his new book and his dyspeptic views on the necessary decarbonization transformation we are accelerating through. Smil was familiar to me due to being one of Bill Gates’ favorite thinkers, asserting that he’s read most of Smil’s 39 previous books. My focus on Gates and his influences was due to his tremendous, and mostly ill-advised, efforts around climate action, including Breakthrough Energy Ventures and his own companies such as Terrapower.

Gates receives nothing but praise from me for the work that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation does on global disease prevention and eradication. That field is one of the three that Gates’ and I overlap at least slightly in, as I helped build the world’s most sophisticated pandemic management solution in the late 2000s in the aftermath of SARS. I appreciate deeply the work that the foundation, funded with Gates’ billions and guided by the Gates’, is doing globally. His efforts through COVID-19 have been stellar, and sadly maligned.

However, this article isn’t about that. This is about another area where Gates’ and I overlap, climate solutions. I’ve been publishing stories about Bill Gates’ engagement in this space for years, and I’ve been deeply perplexed as to why he gets disease so right and climate action so wrong. I’ve published on his investments in the air-carbon-capture-to-fuel boondoggle Carbon Engineering and the useless industrial component Heliogen. I’ve published on his lobbying of Congress to extend federal subsidies for nuclear to small nuclear reactors based on his long investment in Terrapower. I’ve published on his funding of research into solar geoengineering. My assessments are almost entirely negative. With the exception of Breakthrough’s more recent investment in a redox flow battery company, my take is that he’s squandered his efforts and money to little effect. He could do much better than he has.

So the question is, why? He’s a deeply strategic and brilliant man who can afford to surround himself with solid advice. Why does he keep getting it wrong? Well, a lot of the roads lead to Winnipeg, Manitoba. Yes, much of Gates’ climate solutions investments are shaped by Vaclav Smil’s analyses.

I haven’t read all of Smil’s books, but I did analyse his primary publication on the energy transition to gain a perspective on why Gates keeps getting it wrong on solutions to the most important issue of the 21st Century. To be clear, I’m not casting aside all — or even much — of Smil’s work and analysis, just a subset of his perspective on energy, especially around renewables. From my perspective, he gets a few things wrong which leads him to incorrect conclusions. And his influence means that people like Gates end up wasting money. That’s a challenge. Neither Smil nor Gates are climate change deniers in any sense of the word. This is a discussion of solutions.

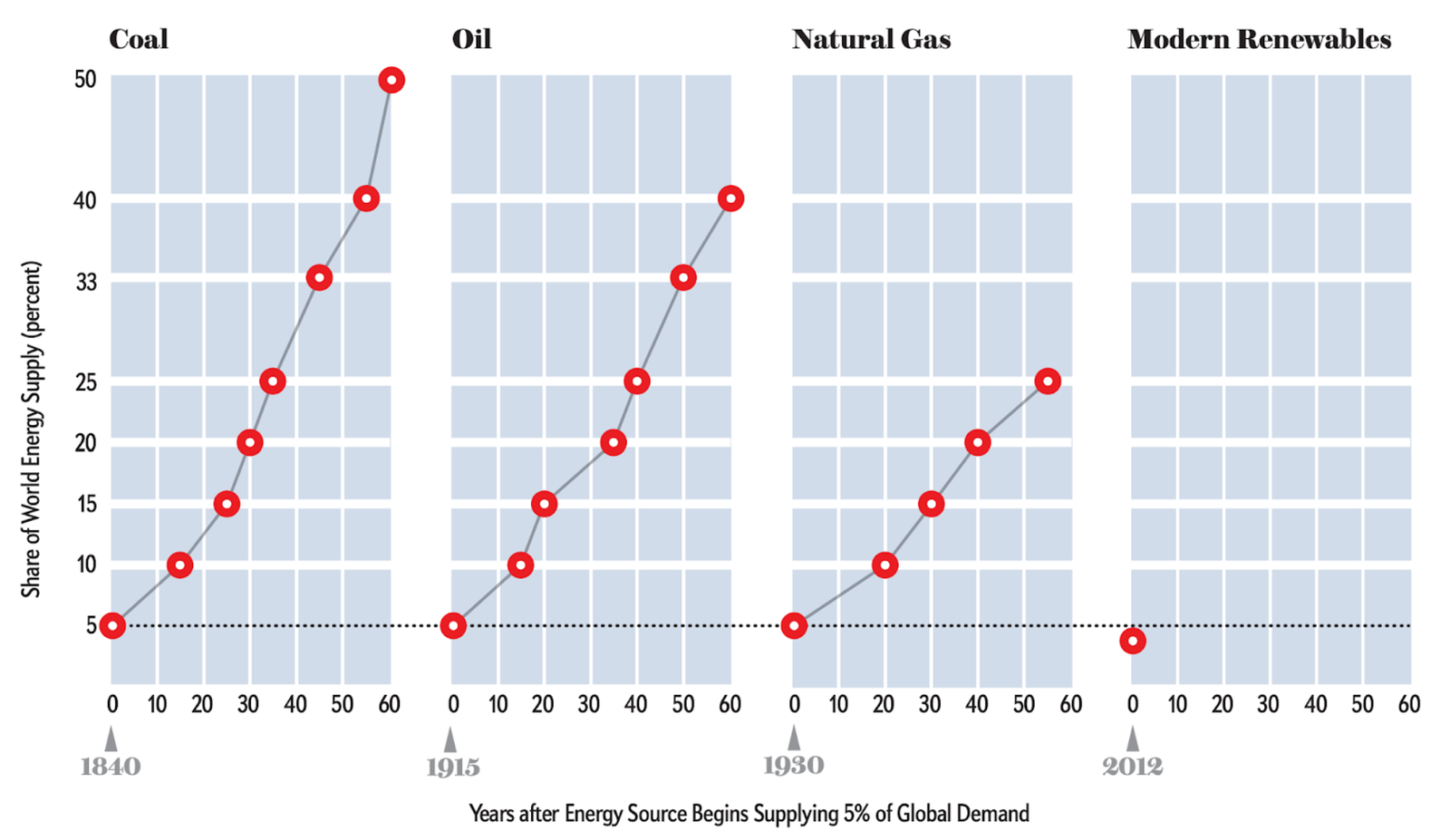

First, that energy transitions take a long time, 50–60 years. Second, that the dominant transition right now is to natural gas from coal. Third, that renewables represent a small portion of overall energy supply, so it’s going to take 50–60 years for them to become the dominant form of energy, especially as hydro is a mostly tapped out resource with only remote, and hence much more expensive, sites left to develop.

Are any of those assertions incorrect? Well, yes, in at least three ways, Smil gets it wrong.

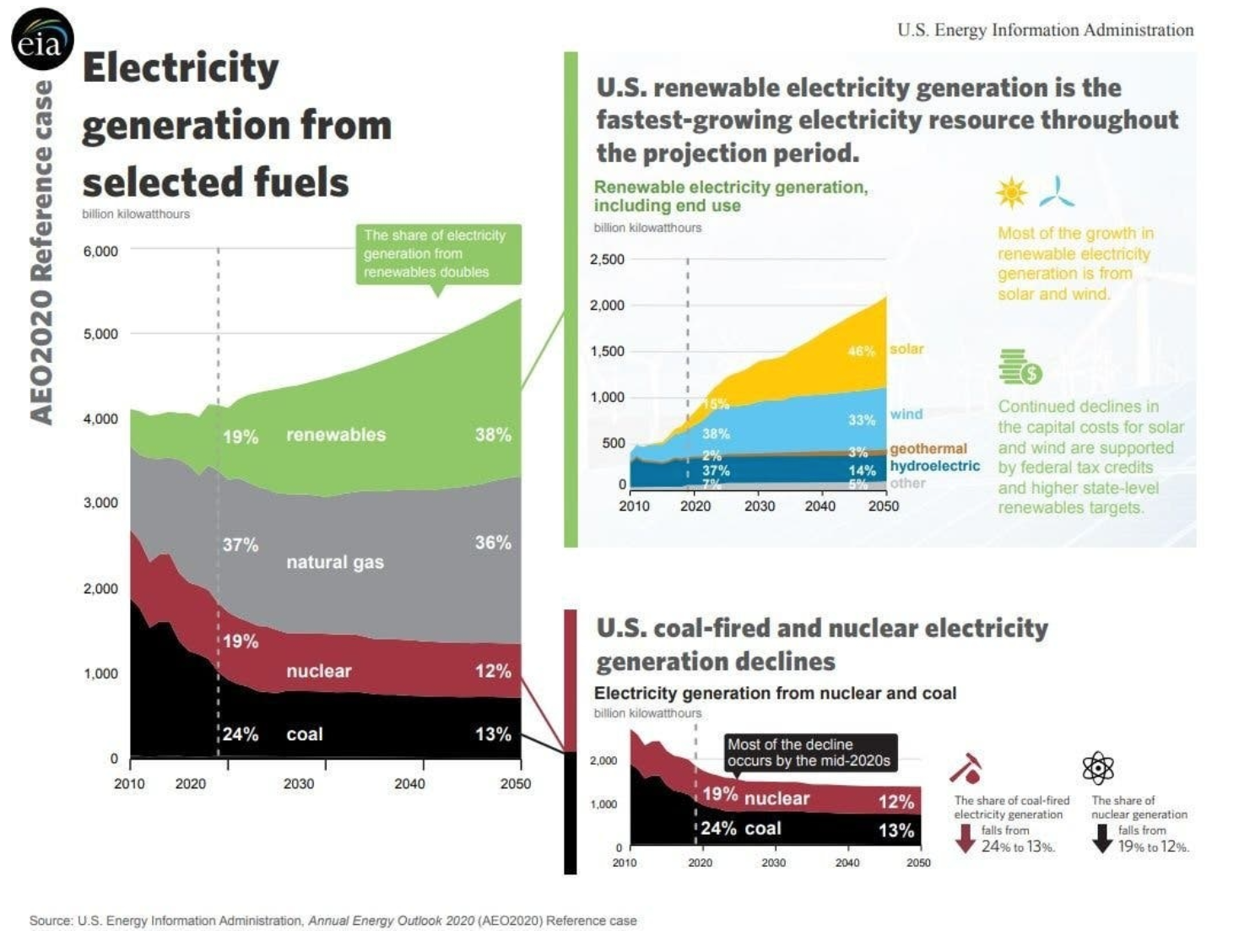

Its growth rate has already slowed while renewables have accelerated. 2019 saw massive bankruptcies sweeping the gas sector as fracking proved to be an expensive, debt-laden, revenue-light pipe dream. Foreclosures and even seizing of property was becoming the norm. Then COVID-19 put a global damper on all energy demand, but natural gas was hit hard as well. The Saudi Arabian and Russian price war on oil is aimed as much at North American producers as any, and this year is seeing massively more bankruptcies, shutdowns, and mergers in the oil and gas sector. But the bloom was off those stocks already, starting in about 2015, about a decade after coal stocks started getting hit.

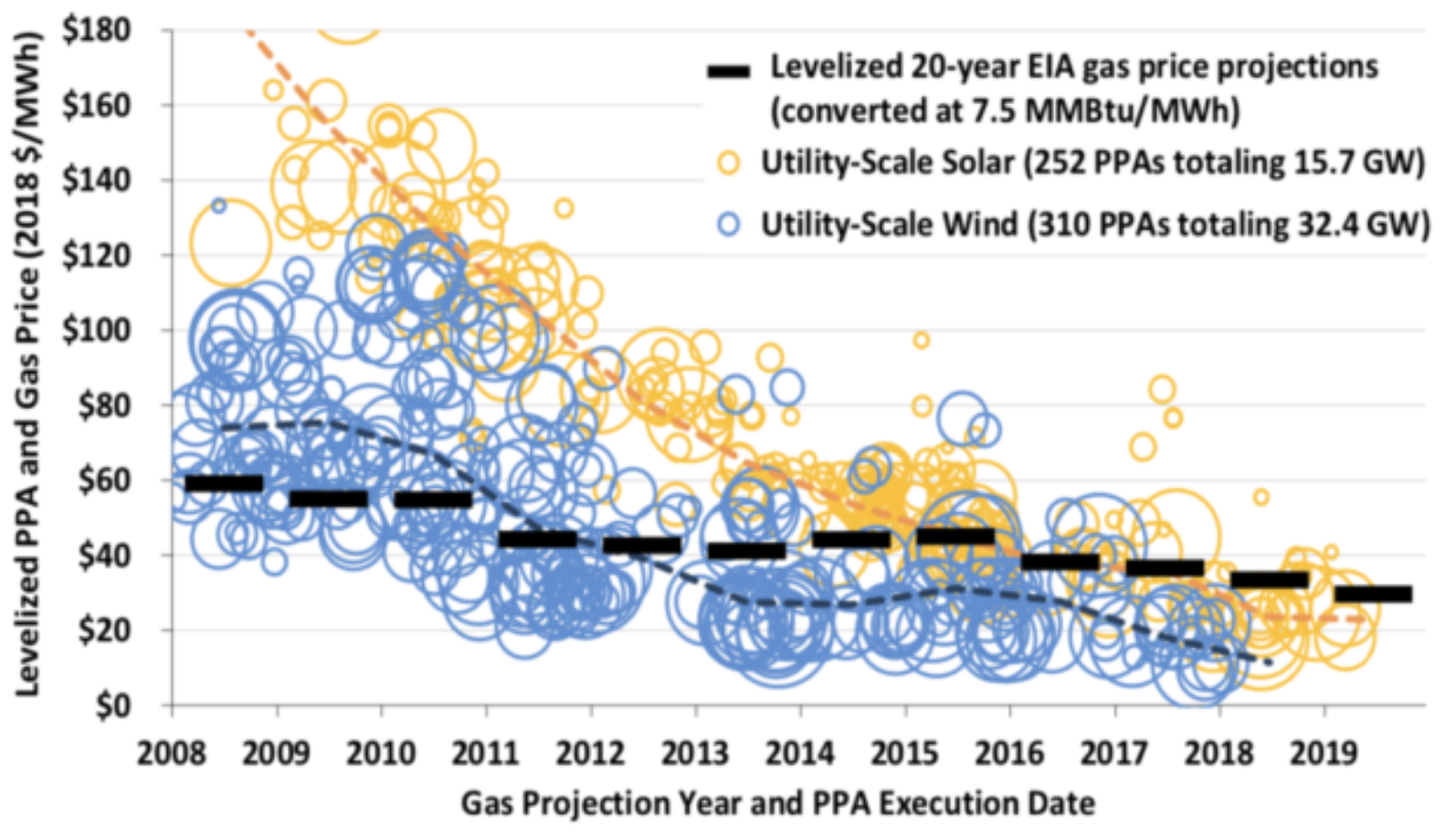

This was before the recent Russian invasion of Ukraine, and hence acceleration away from natural gas and toward renewables in most of the world. Globally, the transition to natural gas is stalling and being displaced by even cheaper renewables. There will be no great transition to natural gas as Smil seems to think. Instead, there was a mini-transition from coal to natural gas, and now both are being displaced. Capacity factors for gas plants are starting to drop already. In the US and in many other markets, wind and solar PPAs are coming in well under natural gas PPAs, and it’s hard to justify a 20-year commitment to spending more on electricity when you could be spending less.

Smil is silent on the subject, which is a glaring oversight. I’ve searched for Smil commenting on energy flows or rejected energy with no results, and the paper cited where he lays out his thesis that renewables won’t cut it ignores this entirely.

See that huge gray box on the upper right, the biggest box on this chart? That’s all the primary energy that gets thrown away due to losses in conversion to useful forms of energy, in distribution or in use. The vast majority of that is waste heat from burning fossil fuels.

Why is this important? Well, it’s important because we don’t have to replace all of the primary energy we use today, we have to replace the energy used productively in energy services as efficiently as possible.

Smil seems to ignore the electrification of everything which is running in lockstep with the growth of renewables. Electric buses are already cutting into oil demand to the tune of hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil a day. Heat pumps are a massive growth market displacing gas furnaces and less efficient air conditions globally, with one of the world leaders, Daikin, building a megafactory for them in Texas.

Primary energy demand is going to shrink, not grow. Electricity is vastly more efficient to distribute and is vastly more efficient to transform into useful electricity services. That’s why everything is already trending there. And solid state electronics are making formerly energy gulping electrical appliances and making them vastly more efficient as well, with LED lights being only the most obvious example.

Because Smil misses the shrinking scale of the problem, he overstates it.

Smil doesn’t seem to understand renewable economies of scale, or to weight it sufficiently if he does. This is understandable, as few people have direct experience of horizontal scaling aka scaling by numbers — building more smaller things in parallel — and most energy analysts who were experienced dominantly with vertical scaling — making individual generation units bigger — got it wrong too. Look at IEA’s long history of failed projections on wind and solar growth over the past 20 years, something that they are finally starting to get right. People who like nuclear energy tend to think of the number of wind turbines and solar panels as a weakness, but it’s actually a massive strength.

My direct experience with this comes from the computer industry I spent much of my career in. Massive mainframes were outcompeted by lots of small computers running in parallel, and small computers plummeted in price while mainframes remained very expensive.

There is about 840 gigawatts (GW) of nameplate capacity of wind energy right now globally. The average wind turbine is between 2.0 and 2.5 megawatts (MW) in nameplate capacity, as new ones are almost always bigger and often much bigger. That means that there are about 350,000 wind turbines that have been built, and it means that there are over a million wind turbine blades turning today. Similarly, there’s about 700 GW of solar capacity globally. The average solar panel is about 200 Watts in capacity, so that’s about 3 billion solar panels installed already.

With those big numbers come massive economies of scale in manufacturing, massive economies of scale in distribution, and massive economies of scale in construction. The vast majority of innovation that’s caused plummeting costs of wind and solar are due to economies of scale, not technical innovation, although that’s been beneficial as well.

I published an analysis last year on the natural experiment in China of how this plays out. It showed that for the decade from 2010 to 2020, both wind and solar fastly outbuilt nuclear. Renewables are vastly more scalable than legacy forms of generation, and Smil misses that entirely.

That analysis was sufficiently compelling that one of the world’s foremost academics of infrastructure projects, Professor Bent Flyvbjerg, Chair of Major Programme Management at Oxford University's Saïd Business School, is including it in a chapter of his book to be published in 2023. His focus is on increasing speed and decreasing risk with modularity instead of megaprojects, and China’s natural experiment was strongly illustrative of his previous research and findings. A key point Flyvbjerg focuses on is Wright’s Law aka the efficiency curve. That’s a well-known and constantly revalidated finding that every doubling of manufacturing of items leads to 20% to 28% cost reductions per item.

Wind and solars’ hundreds of thousands and billions of items continue to make costs plummet for them, something Smil seems unaware of.

Side note: for those hoping that this will be to small modular reactors’ benefit, no it won’t. They forego the advantages of vertical scaling required for thermal generation to be inexpensive, the reason why most nuclear plants are closer to a GW in capacity than not

What’s the result of all of this? Accelerating demand for renewables, slowing or declining demand for natural gas, and declining primary energy demand coming soon to an energy market near you.

While I agree with Smil that it will take “a long time,” my assertion is that by 2050, we’ll be 90% of the way to 100% renewables. Further, it’s entirely possible to be 90% of the way there by 2040 if we put our backs into it. In other words, Smil is off by a factor of two or more in his timeline projections. I don’t agree with Professor Mark Z. Jacobson of Stanford, best known for his regular publication of updates to 100% renewables by 2050, now covering 143 countries, about everything either, and have discussed this with him in, but he’s far more right than Smil is.

And as a result, people like Bill Gates throw away their money on the wrong investments: small nuclear, air carbon capture, and solar geoengineering. Gates and others should listen to Mark Z. Jacobson more, and Smil less.

Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem nor of their employers.

A version of this article is also published in CleanTechnica.

illuminem briefings

Carbon · Environmental Sustainability

illuminem briefings

Carbon Regulations · Public Governance

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

Politico

Climate Change · Agriculture

UN News

Effects · Climate Change

Financial Times

Carbon Market · Public Governance