The power of creative thinking to unlock green finance for cities!

· 10 min read

Traditionally, local governments (LGs) have viewed their role only as providers of public infrastructure and civic amenities. But in the present context, where cities have cemented their status as disproportionate contributors to climate change and are responsible for a staggering 75 percent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, LGs can no longer continue to function in a business-as-usual scenario.

With cities under tremendous pressure to achieve climate targets towards becoming carbon-neutral by 2050, LGs have often tended to adopt a conservative approach, channeling their limited resources on measures that fall directly within their purview. However, given that the bulk of GHG emissions come from privately-owned assets in the built environment (existing and new residential and commercial buildings) and transportation (cars, motorcycles, etc.) sectors, LGs will need to step up and widen their scope to effect high-impact changes across the public and private sectors.

So, how can LGs lead the change? Firstly, by expanding their mandate to encompass a visionary and long-term approach to climate mitigation and adaptation. Secondly, by recalibrating their role: from being ‘providers’ of essential services to becoming ‘enablers’ of holistic and well-planned solutions across the public and private sectors. And, lastly, by overcoming a historical reluctance to borrow from financial institutions (FIs) in order to invest in impactful projects and measures to meet their decarbonization goals.

As the world unites to take decisive and meaningful action on the climate crisis at COP28, this article demonstrates how cities around the globe are thinking out of the box to mobilize green finance by accessing creative financial mechanisms to support at-scale implementation of low-carbon solutions.

Green cities can open pathways to funnel resources into decarbonizing key sectors. However, the implementation of green measures – either in the form of climate-smart infrastructure and service delivery or through enabling policy changes – requires investment.

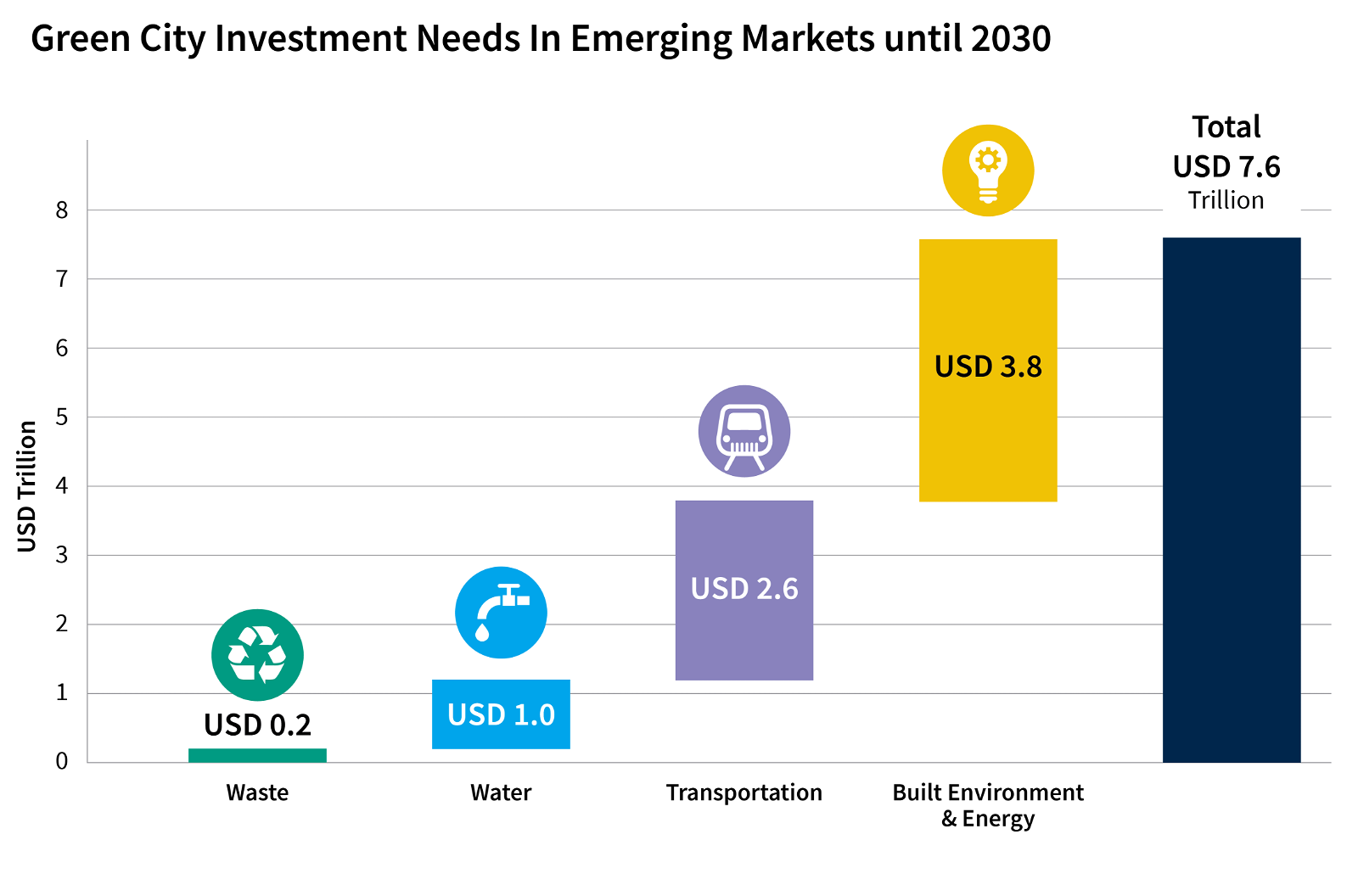

IFC, the private sector arm of the World Bank, estimates that cities in emerging markets represent a USD 7.6 trillion green investment need between 2023 and 2030.

Source: IFC

Green investments can rewire the way cities function by decoupling economic growth from negative environmental consequences. For example, recently, Cape Town Mayor Geordin Hill-Lewis announced that the city would design, build and operate a solar PV plant with battery storage to the tune of 1.2 billion Rand (US$65 million) to reduce reliance on Eskom, the state-owned utility company which is the largest producer of electricity in South Africa. This project will help Cape Town increase profitability, ensure reliable electricity supply and help reduce GHG emissions.

As evidenced, the business case for investing in the greening of cities are manifold:

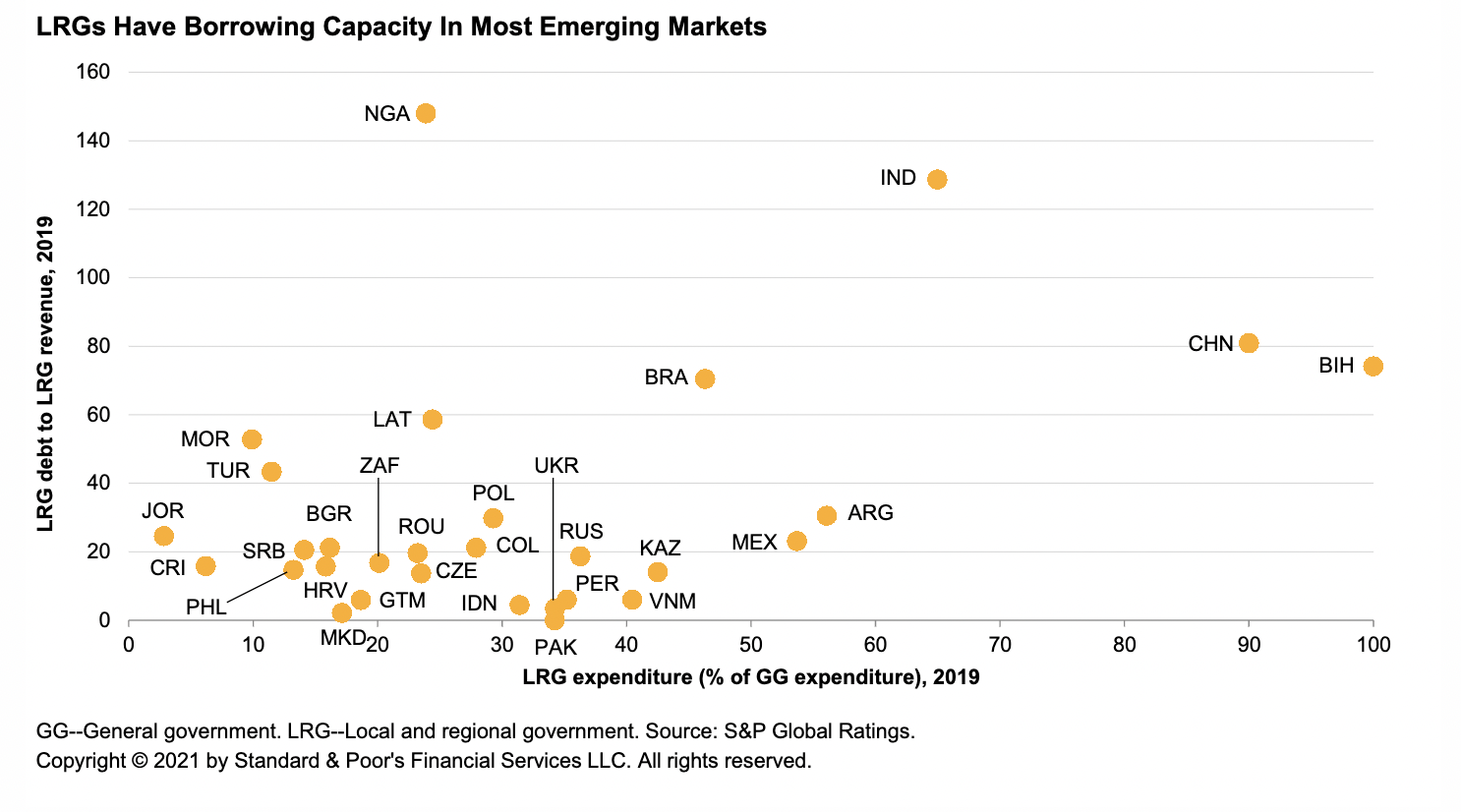

Even in markets where subnational entities are in a position to borrow, creditworthy LGs are often hesitant to borrow, due to regulatory hurdles, economic uncertainty and the unavailability of proven market-based financing instruments.

Source: S&P Global

With international climate change targets at risk of failing, the need to leverage green finance has crossed the line from a “nice-to-have” to an urgent call to action. Cities can actively bridge the urban climate investment gap by exploring innovative ideas for municipal financing options and mobilization through indirect or private sector resources.

Cities can leverage and benefit from partnerships with the private sector to action big-ticket measures and/or those with revenue generation or cost savings potential. Here are three examples:

1. Climate Performance-based Loans or Bonds

Performance-based financing can help cities access lower-cost debt to finance municipal investment projects and receive financial benefits from meeting targets. Also known as sustainable-linked loans or bonds, these on-balance sheet debt instruments focus on key performance indicators (KPIs), such as reductions in GHG emissions, and rely on robust datasets to measure progress. Unlike other types of sustainable finance instruments, these performance-based instruments do not impose restrictions on how the funds are to be used.

The examples below demonstrate the promise of this innovative financial instrument:

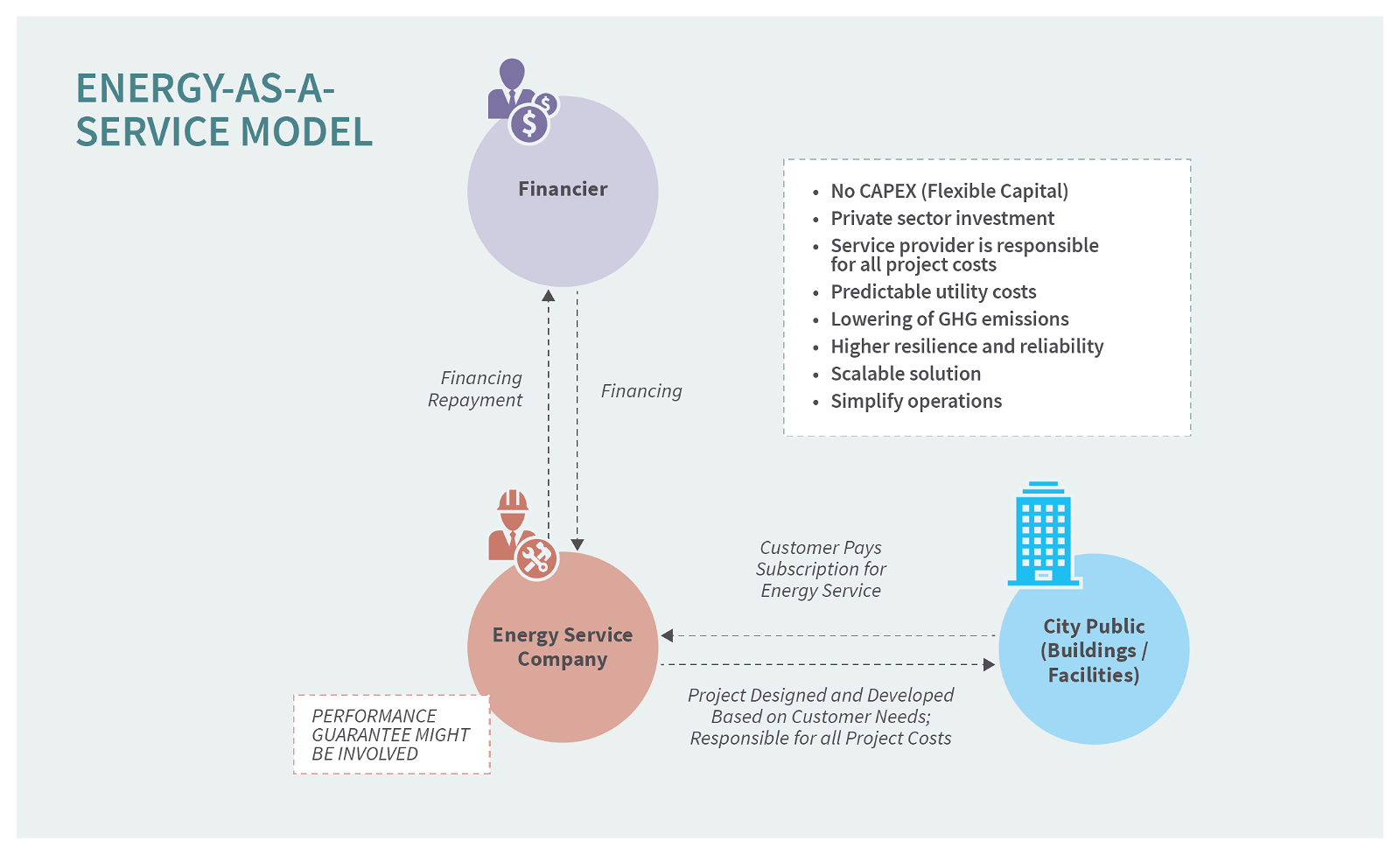

2. Energy-as-a-service/energy performance contracts

A form of the “as-a-service” business model, an energy performance contract (EPC) enables funding of energy efficiency upgrades from the corresponding energy cost reductions. Under an EPC arrangement, an external organization, typically called an Energy Service Company (ESCO), implements an energy efficiency project and uses the stream of income from the cost savings to repay the project costs. An off-balance sheet financing option, cities can take advantage of this model to reduce their carbon footprint without having to incur upfront costs or utilize public funds. Potential areas of application include energy and water efficiency technology upgrades, low carbon heating and cooling, rooftop solar, public lighting, and electric vehicles, among others.

EPCs are increasing in popularity and garnering the attention of LGs in North America, Europe, Asia Pacific, Latin America, as well as the Middle East and Africa.

Source: IFC

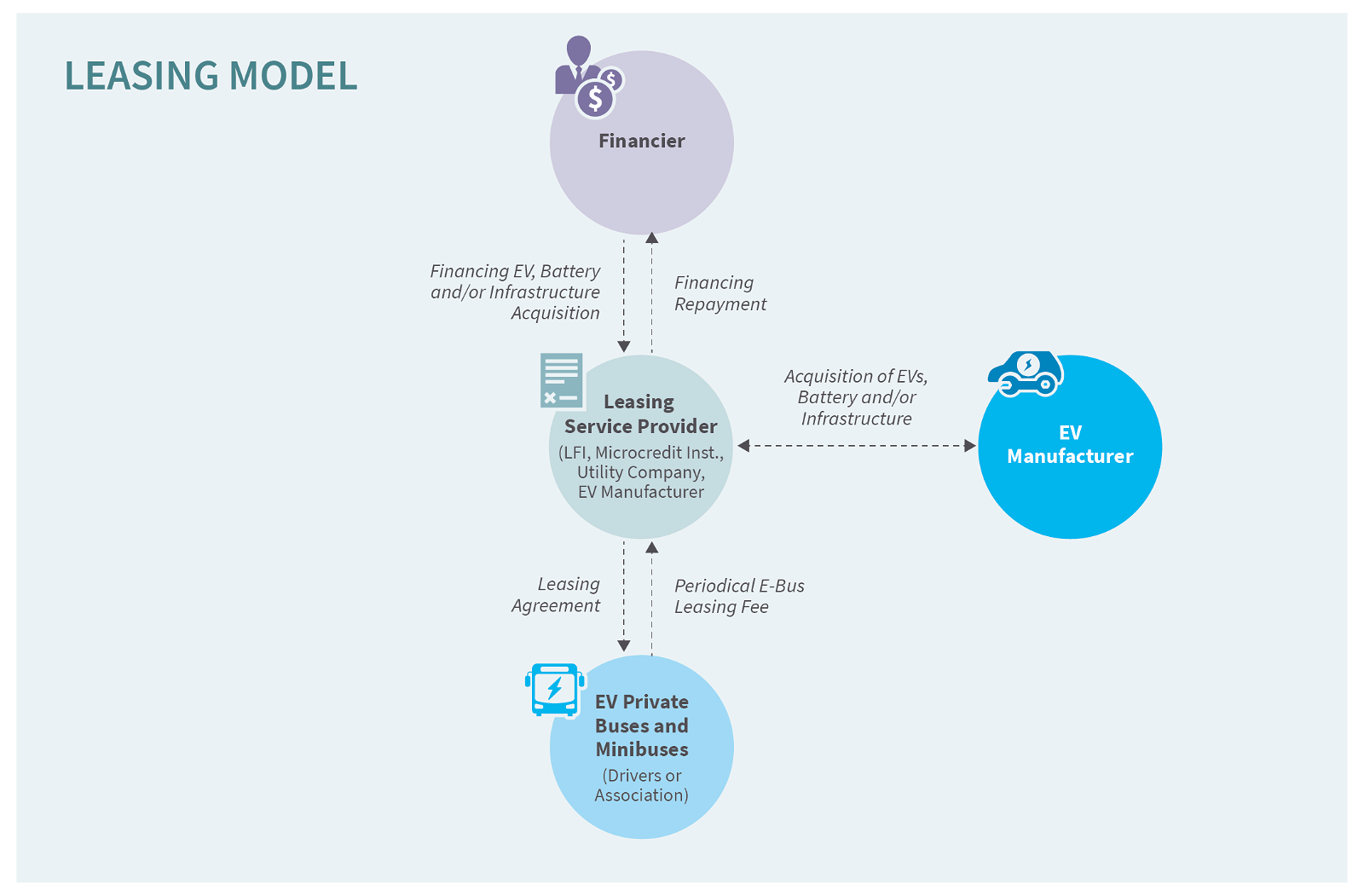

3. Finance for e-bus and taxi fleets

Though electric buses comprise only about 13 percent of the total global bus fleet, they are the fastest-growing electric vehicle segment over the past five years. LGs can encourage and promote the use of electric vehicles (EVs) in the public transportation sector by supporting the acquisition and operation of privately owned electric buses, minibuses, and taxis.

Leasing is a well-established approach to vehicle financing that is also applicable to EVs. Instead of paying the total cost upfront, the vehicle operator agrees to pay the entity a specific monthly amount for an agreed period for the use of an EV or e-bus. At the end of the lease agreement, the operator could have the option to either return or buy the e-bus. The leasing service covers the full EV package, including the vehicle, battery, and/or charging infrastructure.

Source: IFC

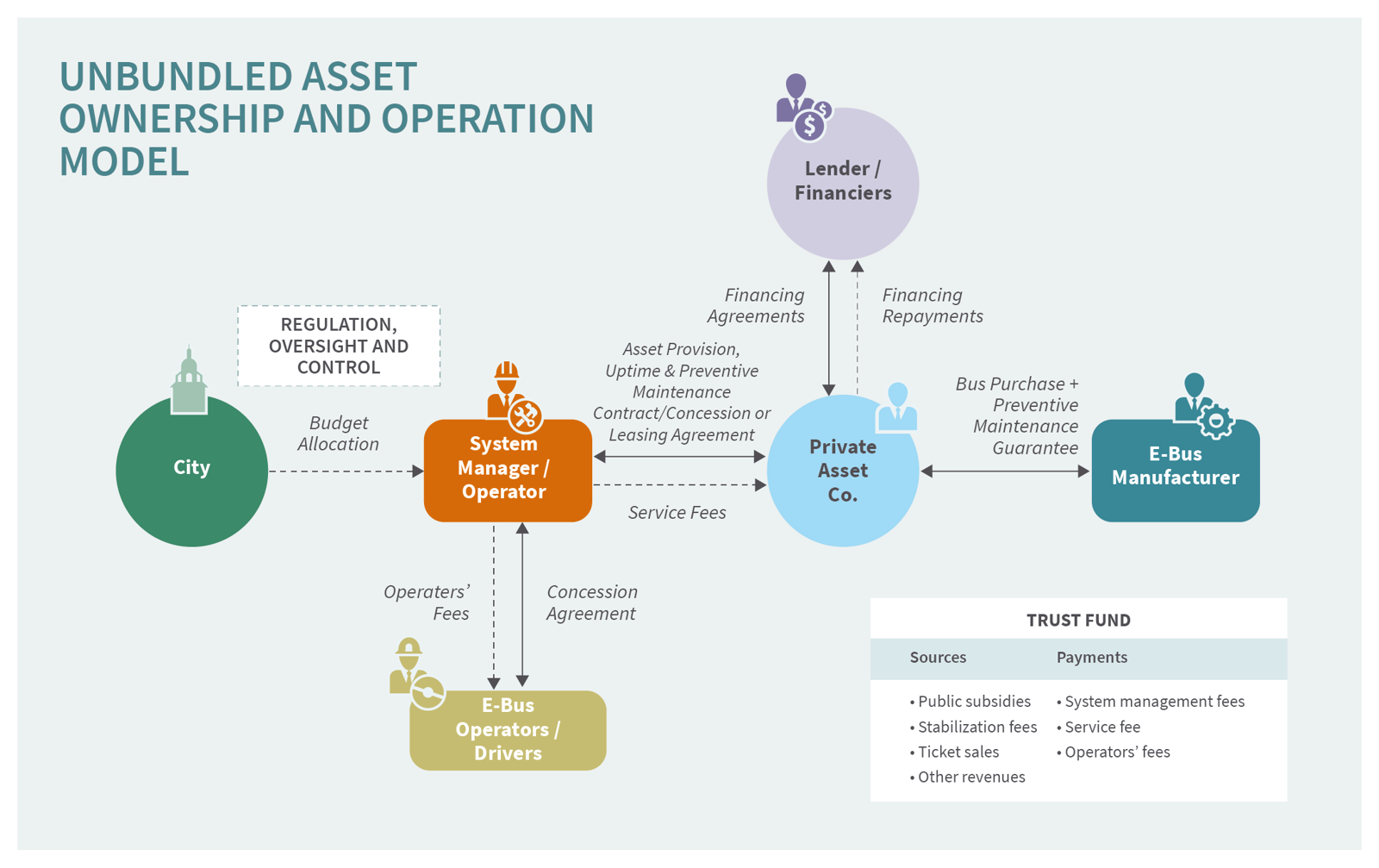

Unbundled asset models, where asset ownership and operation are handled by different parties, have also emerged as successful models for overcoming risks and high upfront costs associated with switching to e-buses. In such unbundled models, an asset company (or companies), which can be private or public sector-led, procures and owns e-buses that are made available to operators under a fleet provision agreement with the transit authority covering fleet provisioning, maintenance and supervision responsibilities.

Source: IFC

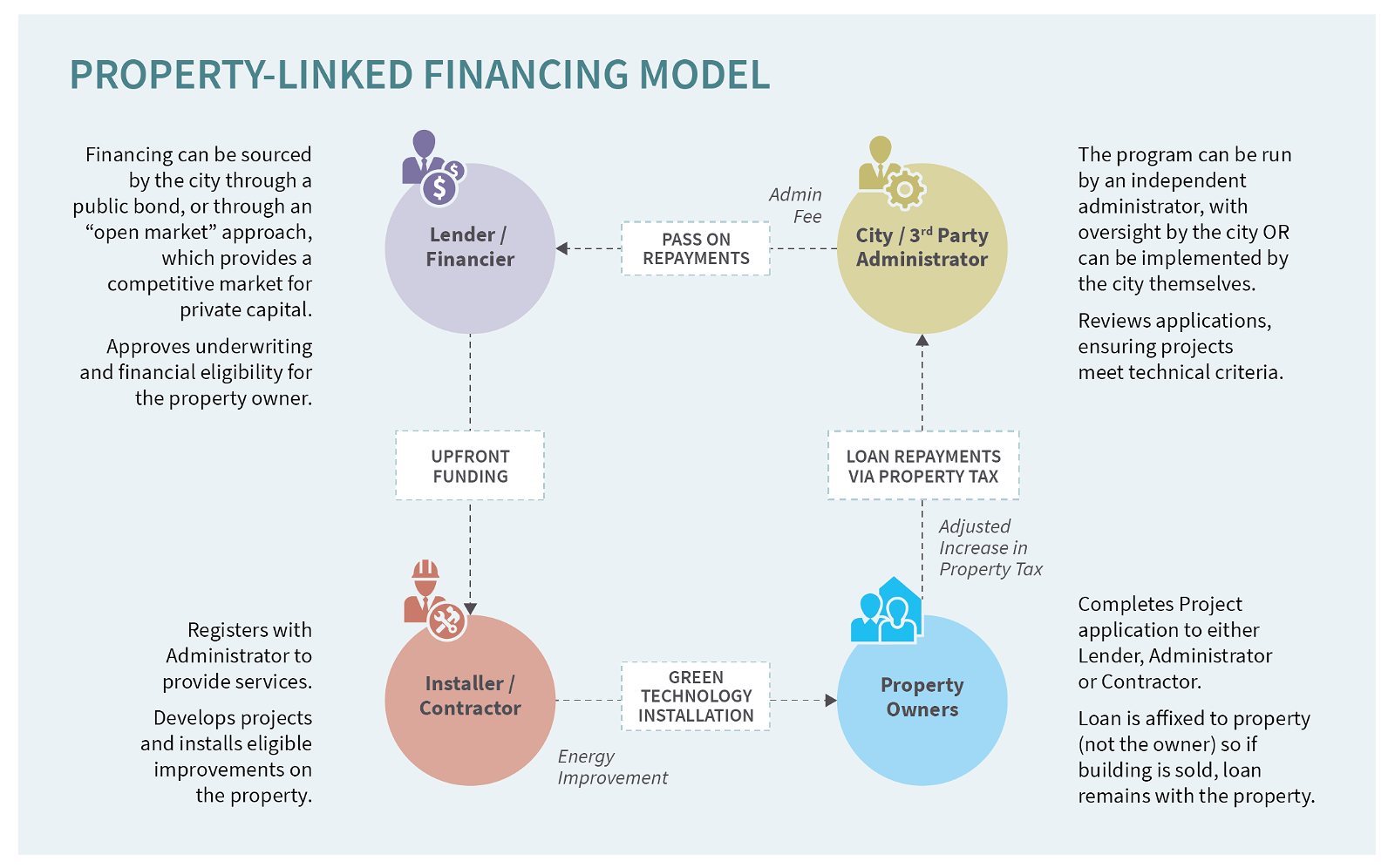

To accelerate decarbonization of privately owned assets, LGs can play an enabling role in structuring a mechanism like property-linked financing (PLF) that facilitates the implementation of EE upgrades for buildings. LGs can also play a regulatory role in building climate-smart communities by nudging local financial intermediaries and upgrading urban policies.

1. Property-linked financing

Known as Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) in some countries, PLF supports the long-term funding of EE upgrades of residential and commercial buildings. Set up as an assessment through a building’s property tax, the borrowing acts like a lien against the property, where the loan is attached to the building and not to the owner.

Source: IFC

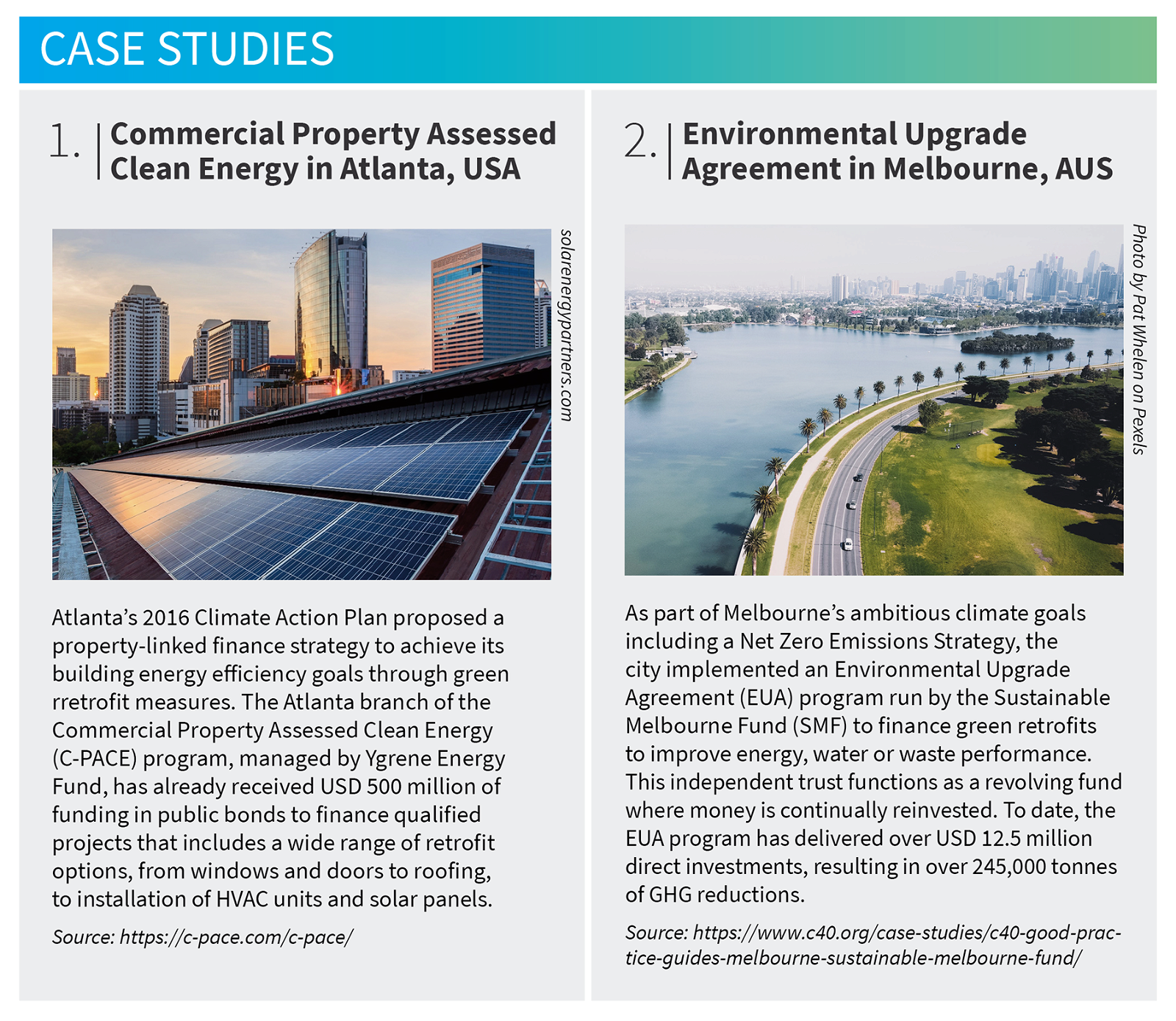

PLF covers the high upfront costs of deep energy retrofits and yields immediate payback, which incentivizes owners to opt for the most effective measures. Moreover, since it is difficult for cities to regulate existing buildings, a program like PLF provides the perfect framework to support cities’ decarbonization goals. The LGs of Atlanta, USA and Melbourne, Australia are successfully implementing PLF to carry out at-scale city-wide decarbonization efforts:

2. Nudging local financial intermediaries

LGs can also play an enabling role that focuses on regulations and incentives for local financial intermediaries (FIs) to facilitate decarbonization efforts in the private transportation and the built environment sectors. By supporting FIs to promote initiatives such as offering tax incentives for EV purchases or mobilizing the provision of green mortgages (i.e. loans reserved for houses meeting certain environmental criteria) or solar home equity loans, LGs can encourage citizens to adopt an environment-friendly lifestyle.

Key aspects of this mechanism include:

3. Innovative planning and policy upgrades

The urban infrastructure, which includes residential and commercial buildings, private and public transport networks, water and electricity networks, and service delivery systems, determines cities’ energy use and carbon emissions. Convening cross-cutting planning strategies and formulating policy innovations are instrumental to ensuring green urban development, and LGs can leverage market and policy tools to drive value creation. Here are a few examples:

A thriving mixed-use neighbourhood in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. Image credit: Prashant Kapoor/IFC

If the climate battle is to be won in our cities, the onus rests squarely on whether regulatory policies and finance can align. As COP28 brings diverse stakeholders together, it's important to recognize that the greening of cities is in everyone's best interest. By exploring creative ideas around climate finance mechanisms, LGs can facilitate robust collaborations that bring together the public and private sectors with a shared objective: enabling green investment pathways to decarbonize and rebuild climate-smart cities, transforming them into thriving communities.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Subscribe to our COP28 newsletter here to get comprehensive coverage of the world's largest climate conference delivered straight to your inbox.

This article is featured in illuminem's Thought Leadership series on COP28 proudly powered by Tikehau Capital.

illuminem briefings

Pollution · Nature

illuminem briefings

Pollution · Cities

illuminem briefings

Cities · Sustainable Living

Euronews

Pollution · Cities

CNN

Pollution · Cities

Politico

Carbon · Pollution