Taking the politics out of climate change

· 5 min read

💡 This article is featured in The Definitive Reading List: illuminem’s Recommended Sustainability Classics

“97% of scientists … have now put that to rest. They’ve acknowledged the planet is warming and human activity is contributing to it”.

Barack Obama booms these words at the start of a video titled “Senator Ted Cruz is a Climate Change Denier.” If that wasn’t convincing enough, “97% OF SCIENTISTS AGREE” takes up the screen 18 seconds in. Senator Cruz is labeled a “CLIMATE CHANGE DENIER” and “RADICAL AND DANGEROUS.” The video couldn’t make its point any more powerfully.

It could. The reasons why apply not only to this video but also to similar messages are given in other forms. At least six high-profile studies were published between 2004 and 2012 highlighting the scientific consensus on global warming;1 the 2006 Academy Award-winning documentary An Inconvenient Truth paints a similar picture. Yet, public understanding of climate change hasn’t improved. In 2003, a Gallup poll found that 61% of people believed that climate change is man-made rather than natural; by 2013 this had dropped to 57%. Of course, this data isn’t conclusive, because we don’t know the counterfactual – what it would have been without those studies and movie – but there hasn’t been the epiphany we’d have hoped for.

A leading explanation is the cultural cognition hypothesis. People respond to a message based not on the evidence behind it but on the cultural identity it signifies. The problem with the video ridiculing Cruz is that it made climate change an issue not just of science but of politics, suggesting that liberals believe in it and conservatives don’t. A Republican viewer might think he needs to be a skeptic if he wants to call himself a proper Republican, irrespective of what the science says. An Inconvenient Truth was also loaded with evidence, yet because it was about Al Gore, it politicised the topic. Climate change then becomes less about “What do you believe?” and more about “What group do you belong to?”

The cultural cognition hypothesis means we can’t think about facts, data, and evidence in a vacuum. Data is never just data; we don’t evaluate it only on its quality but by whether it supports “them” or “us.” Similarly, we support or oppose conclusions not based on the evidence behind them, but whether they’re the sort of things “people like them” or “people like us” tend to say. As a result, to create more informed, smarter-thinking societies, public messaging needs to disentangle evidence from identity.

One step is to resist the temptation to ridicule opponents, such as laughing at Republicans for ignoring an apparent 97% scientific consensus. While doing so might give a short-term dopamine hit, it makes it much harder for the other side to focus on the evidence. One otherwise informative article was entitled “A Tutorial On ESG Investing In The Oil And Gas Industry For Mr. Pence And His Friends.” In addition to slighting the intended audience by suggesting they needed a tutorial but others don’t, it also politicised the issue, implying that true Republicans should be anti-sustainability. A leading sustainability practitioner wrote “I don't know about you, but when I see the likes of Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, Greg Abbott, Mike Pence, and Elon Musk railing against ‘ESG’, I know ESG must be doing something right.” But the criterion for the success of ESG is whether it creates long-term value for shareholders and society, not whether it riles conservatives.

A second, and more positive, action is to ensure that important messages are given by people with a different political stance (or no stance at all), such as a conservative highlighting global warming or a doctor explaining what America’s Affordable Health Choices Act in fact proposed. In June 2021, Republican Representative John Curtis launched a Conservative Climate Caucus to encourage his party to take climate change seriously. It was backed by nearly a third of the Republicans in the House of Representatives.

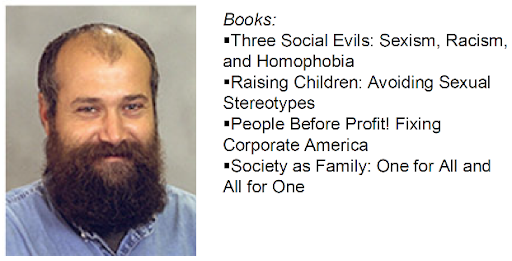

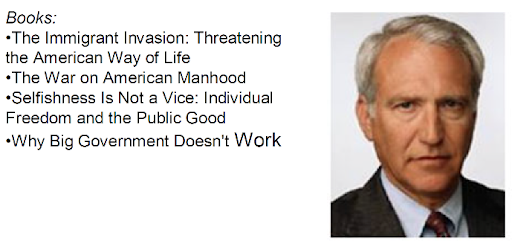

A study by the Yale Law School’s Cultural Cognition Project investigated mandatory vaccination against the human papillomavirus (HPV).2 As we’d expect, right-wing subjects were more likely to oppose vaccination than their left-wing counterparts. Particularly interesting was a second experiment where, before giving their views, people first read arguments on both sides from experts whose profiles would likely be identified as left- or right-wing:

When the person at the top gave the pro-vaccination case and the right-wing guru opposed it, the gulf between the views of right-and left-wing participants widened. If instead the right-wing advocate defended vaccination and the left-wing commentator opposed it, polarisation shrunk.

A third approach is to shift the focus from problems to solutions. People are more willing to acknowledge the disease if they agree with the cure. Another study found that right-wing participants were more willing to accept that climate change is a serious threat if the remedy is geoengineering – launching solar reflectors, injecting aerosol particulates into the stratosphere, and capturing carbon to store it in deep geological formations – rather than regulation. This solution links climate change to cultural meanings of human ingenuity and industrial innovation, which resonate with free marketers and help them view climate action as an opportunity, not just a threat.

This article is extracted from “May Contain Lies: How Stories, Statistics, and Studies Exploit Our Biases – And What We Can Do About It” (Penguin Random House, 2024). illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Kahan, Dan M. (2015): “Climate-Science Communication and the Measurement Problem.” Advances in Political Psychology 36, 1-43.

Kahan, Dan M., Donald Braman, Geoffrey L. Ohen, John Gastil and Paul Slovic (2010): “Who Fears the HPV Vaccine, Who Doesn’t, and Why? An Experimental Study of the Mechanisms of Cultural Cognition.” Law and Human Behavior 34, 501-516.

illuminem briefings

Labor Rights · Climate Change

illuminem briefings

Architecture · Carbon Capture & Storage

Barnabé Colin

Biodiversity · Nature

Euronews

Degrowth · Public Governance

Politico

Public Governance · Climate Change

Mongabay

Climate Change · Environmental Rights