Route17 (IV/IV) – The mobilizing private capital equation

· 11 min read

Join us at Terra Tuscany from September 2-4 for a transformative three-day event with world-class sustainability experts. This event empowers your business through practical strategies and collaborative opportunities in an immersive, barrier-free environment. Act fast to secure your spot—tickets are limited! Request your ticket at Terra Tuscany

This is part four of a four-part series on mobilizing private capital. You can find part one here, part two here, and part three here.

This is the fourth and last article in a series we have written about the takeaways from a symposium hosted by Route17 and Dimensional Fund Advisors in September 2023: an invite-only group of approximately 60 representatives from a range of sectors – government, development banks, asset owners, asset managers, banks, academia, and thinktanks – to discuss blended finance and how to scale it.

In the first article, we discussed the “why” of blended finance – closing the $4.2 trillion annual funding gap for SDGs and climate – and introduced the “Mobilizing Private Capital Equation,” the analytical framework developed by Route17 to guide the day’s discussions.

In this framework, we liken the desired output – private capital flowing towards SDGs – to music coming from an amplifier with four dials that can all be turned up or down. The output then is a function of four variables: (1) the supply of bankable projects, (2) the risk mitigation capital and instruments that are used, (3) the links between the development banks (DFIs and MDBs) and the private sector investors and, finally, (4) the orientation of private investors towards this kind of investing.

The four break-out groups in the symposium each discussed one of these dials, and their findings were documented in our previous articles: the first article referenced above discusses the supply of bankable projects (“Bankability”); the second article discusses how risk mitigation capital is used (“Concessionality”); the third discusses the links between DFIs and the private sector (“Marketplace”). This final article covers the last dial: the orientation of private investors towards blended finance (“Mobilization”).

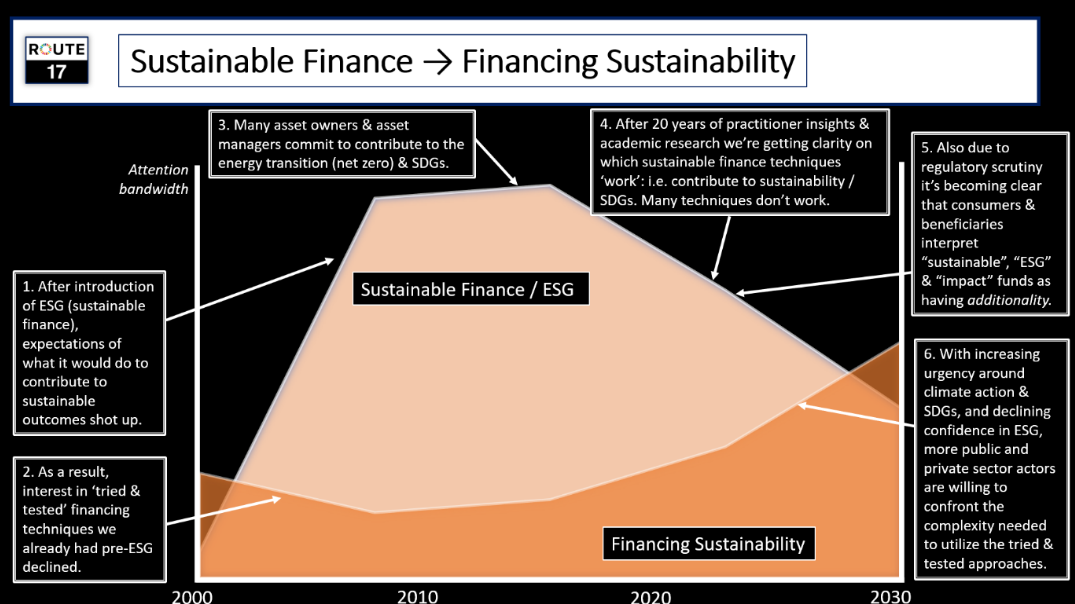

The discussion in this fourth break-out group was prefaced by a discussion about the slide below. With this graph, we demonstrate that many have had high expectations of what sustainable finance (ESG) practices would do to generate “impact” – in other words, contributing to the financing of sustainability initiatives. We also argue that many sustainable finance practices don’t, in fact, generate impact. ESG integration is a good example of this. While integrating ESG factors into investment decision-making can have benefits, enabling real-world outcomes that otherwise would not happen doesn’t appear to be one of them.

As academia, regulators, clients, and investors reach similar conclusions about sustainable finance, more investors are embracing established financing methods like blended finance. While these approaches may be complex and involve collaboration with public or philanthropic entities, they often lead to tangible impact.

We refer to this shift in orientation as “Sustainable Finance to Financing Sustainability.” We believe this shift needs to happen across the financial sector, with asset owners in particular, for investors to play a more active role in the blended finance marketplace (see our previous article) and contribute larger amounts of capital to transactions that generate real, additional impact. And we do see the shift happening.

So, if this shift is, in fact, happening, why is this dial in our framework—the orientation of private investors towards financing sustainability—still considered a barrier?

Well, because the shift is not happening fast enough, certain dynamics are keeping the brakes on. Our discussion during the break-out group focused on identifying these dynamics so investors can take their foot off the brake pedal and shift it to the accelerator.

We identified two categories of constraints, or “sub-dials,” if you will: (1) technical and tangible constraints and (2) behavioral and organizational constraints.

We caveat the analysis below by pointing out that much of the discussion in this break-out group revolved around investments into emerging markets (“EM”) – this is where the participants believed the heavy lifting is needed.

The participants listed many technical issues that need to be addressed in considering blended finance investments and that could be dealbreakers in many situations.

Pricing/benchmarking: Information on how deals are priced and lack of clarity on what asset class returns or benchmarks they should be compared to (e.g., infrastructure).

Ratings: many institutional investors require a rating from e.g., S&P or Moody’s, but blended finance transactions don’t usually come with ratings. Some institutional investors consider internally generated ratings, but developing these is hard work. Often, the minimum rating required is BBB- but many blended finance deals fall below this if they have an (internal) rating.

Risk information: the best source of information on risk aspects of blended finance transactions, such as default and recovery rates, is the GEMs database (kept by the Global Emerging Markets Risk Database Consortium), most of which was not accessible to institutional investors until recently. This should help assess the risks more precisely and remove some of the ‘perceived risk’ that many in the group believed to be a barrier.

Government support: it was observed that until ten years ago, institutional investors weren’t investing in renewable energy in Europe, and they only started doing this because of years of public sector support through subsidies, which can also be considered a form of blended finance. In other words, if we want to achieve the same for EM, it will require similar support through subsidies and/or providing concessional capital for blended finance investments.

Currency risk: Many blended finance investments involve payments in EM currencies, which comes with currency risk. It was pointed out that this risk can often (but not always) be overcome through hedging, albeit at a certain cost, which needs to be factored into the investment case.

Availability: most asset owners depend on asset managers to provide investment opportunities, yet investments in EM, let alone blended finance, are not commonly offered by asset managers. The flip side of this is that asset managers are rarely asked about these opportunities; one investment advisor in the group who works with many UK pension schemes commented, “I have never been asked about this kind of investment.”

Cost: Given the small market size and the complexity of transactions, hiring staff or mandating a manager to focus on this kind of investment can be costly.

Ticket size: the minimum ticket (required size of the investment) is often USD 50m, and in some cases can be much higher; usually, there are also constraints in concentration because asset owners don’t want to be the largest investor in an investment or fund. Effectively, this means the minimum fund size is USD 500m-1bn, and there are still relatively few blended finance funds or vehicles of this size. More generally, it was observed that the well-structured funds, track records, fee profiles, and processes around sourcing and structuring deals that institutional investors look for only come with substantial volume in a market or asset class; blended finance does not have these features yet.

Legal & Regulatory: institutional investors look for stable legal and regulatory regimes in the countries where they invest. However, these are often weaker in EM, especially in relevant but developing sectors such as renewable energy.

ESG data & exclusions: many institutional investors require ESG data for their sustainability due diligence on investments; however, ESG data is lacking for many EM and blended finance projects, which can preclude these investments. In addition, some countries that require funding to meet SDGs or fund climate mitigation or adaptation projects are on investors’ exclusion lists driven by ESG concerns (e.g., human rights), again making any investment impossible, no matter how impactful or attractive financially.

Liquidity / lock-ups: Blended finance funds tend to finance less liquid investments and often have relatively long ‘lock-ups’ (meaning that investors can’t withdraw their money for long periods of time), which is typically not aligned with institutional investor requirements.

The participants in this discussion also listed several constraints that are more organizational or behavioral and, therefore, tend to be less visible than the technical constraints listed above.

Misalignment: many institutional investors commit to impact investing, e.g., to contribute to SDGs or Paris goals, which implies a substantial focus on EM, private markets, and blended finance. However, too few follow up on their commitments by aligning goals and organization, ensuring their staff have the connections, capabilities, and mandates to make EM and blended finance investments.

Mandate: as a result of the previous point, it is also often unclear within asset owner or asset manager organizations which team should take on potential blended finance deals.

Focus on “impact” or “finance”? Some in the group felt there should be more emphasis on the impact, or ‘additionality,’ of blended finance investments, as this would allow investors to see that making these investments would go a long way in meeting their impact commitments. Others felt that emphasis should be mostly on the financial or technical requirements; the thinking was that we should simply try to harness global capital flows by creating investments that meet institutional investment requirements. In this context, there was also the recommendation to do more ‘blind audition’ investing, in other words, to remove references to EM, impact, or SDGs; the thinking was that institutional investors would be more likely to consider them like any other investment and that we avoid preconceptions about (perceived) risk or sub-par returns in EM or blended finance investments.

Asset owners as first movers: It was observed that asset owners tend not to be first movers as new asset classes are created. Principals on the asset owner side need to have the capability to assess, understand, and risk-manage these investments, and this can take a long time to build up.

ESG staff tied up elsewhere: ESG staff within asset owner or asset manager organizations are often considered the logical entry point for blended finance investment opportunities or even as potential advocates and initiators of this kind of investing within their organization. In reality, it was observed that ESG staff spend most of their time doing TCFD reporting, collecting data on CO2 emissions, or taking care of SFDR disclosures. “If I told my boss I’d like to spend one day a week on this kind of investment, that would be very difficult”; “for ESG people it’s a ‘nice to do,’ not a ‘must do’”; “the reporting burden is so vast and doesn’t leave time to engage with development banks, even if our leadership would probably be interested in blended finance”; were some of the comments made.

Reflecting on the day’s discussions and the barriers and constraints identified, not only in this fourth break-out group but in all discussion groups of the symposium, we can’t deny that the challenges to mobilizing more private capital are daunting. Also, there are no simple solutions to many of the identified constraints.

At the same time, we feel confident that, with this group of 60 representatives from across the spectrum of relevant actors, we’ve managed to both reaffirm the strong case for blended finance as well as confirm that our Route17 Mobilizing Private Capital Equation framework identifies and analyzes the knobs we need to turn to dial up the flow of capital.

It effectively also validates an earlier series of articles authored by Route17, “Blended Finance is Like Music.” In these six articles, we discuss what Governments, Asset Owners, Foundations, Development Banks, ESG Professionals, and Asset Managers can do to overcome the barriers to blended finance identified in this symposium.

While we emphasize in these articles that all these actors should move proactively and not play the waiting game, we also firmly believe that government’s role here is crucial: they are the only actors on our list that can put their finger on the scale for each of the four dials in our framework – they can increase the availability of investable projects; as shareholders, they can direct development banks to use the blending toolbox more and more effectively; they have awesome convening power to bring together parties and help build a marketplace; and they can rethink sustainable finance regulations to accelerate the shift from “Sustainable Finance to Financing Sustainability.”

But this is certainly not letting the finance and investment sectors off the hook. So, we’d like to end this series by quoting Bill Gates in his book How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: “The amount of money invested in getting to net zero … will need to ramp up dramatically and for the long haul. To me, this means that governments and multilateral banks will need to find much better ways to tap private capital. … It’ll be tricky to mix public and private money on such a large scale, but it’s essential. We need our best minds in finance working on this problem.”

With this, we fervently agree, and this is also the reason that we established Route17: to work with governments, multilateral banks, and the best minds in finance to solve this problem.

Yes, it’s tricky. But it’s essential.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Charlene Norman

Sustainable Business · Sustainable Finance

illuminem

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

Eco Business

Sustainable Finance · Public Governance

Responsible Investor

Sustainable Finance · ESG

Sustainable Views

Sustainable Finance · Adaptation

illuminem

Corporate Sustainability · Sustainable Business