Route17 (II/IV): the mobilizing private capital equation

· 8 min read

This is part two of a four-part series on mobilizing private capital. You can find part one here, part three here, and part four here.

This is the second in a series of articles we are writing about the takeaways from a symposium that Route17 and Dimensional Fund Advisors hosted in September 2023: an invite-only group of approximately 60 representatives from a range of sectors – government, development banks, asset owners, asset managers, investment and commercial banks, academia and thinktanks – to discuss blended finance.

In the first article, we discussed the “why” of blended finance – closing the $4 trillion annual funding gap for SDGs and climate – and we introduced the “Mobilizing Private Capital Equation”, the analytical framework that Route17 developed to organize the day’s discussions around.

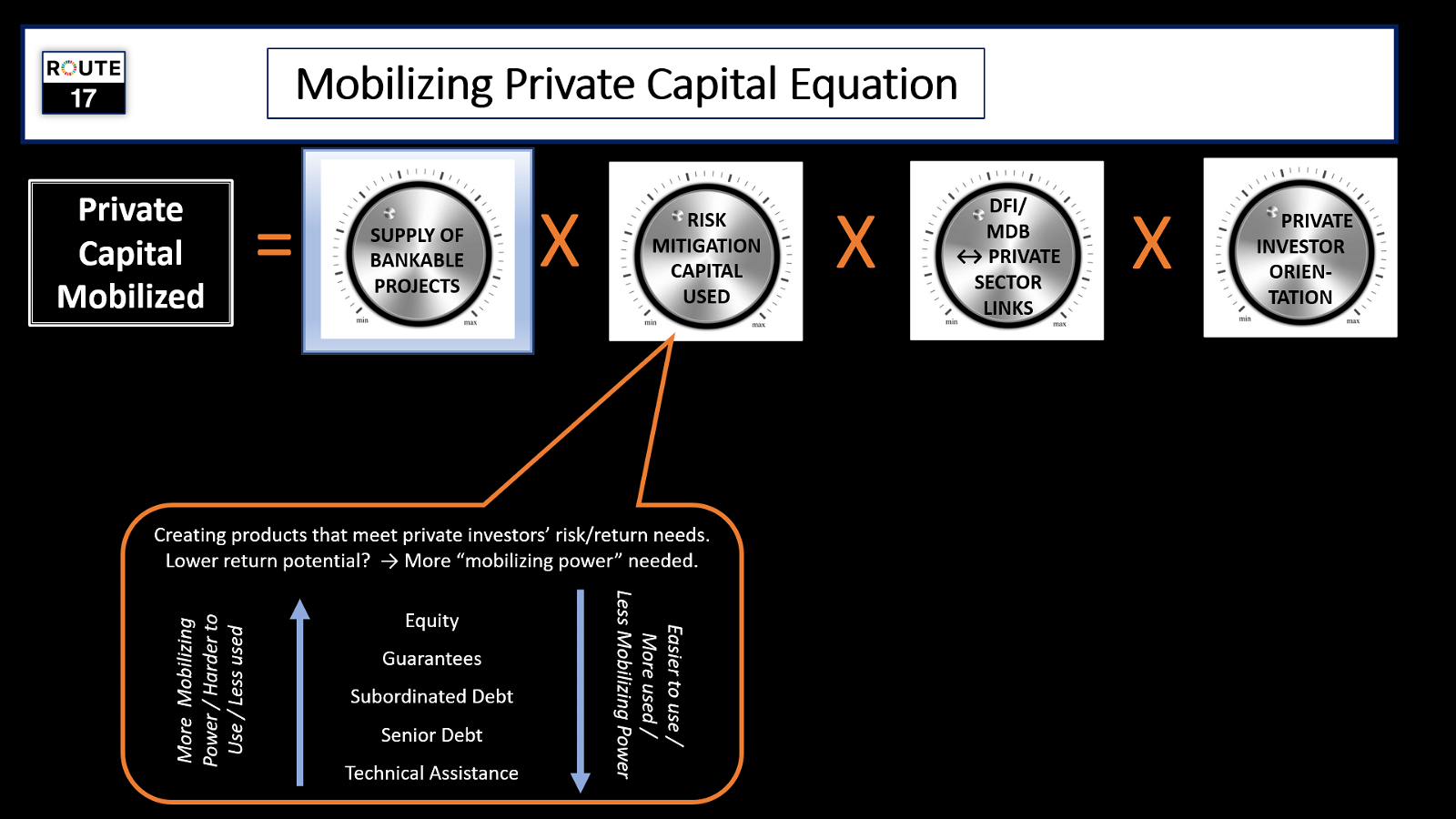

Building on the music analogy we used in our series of articles Blended Finance is Like Music, we liken the desired output – the amount of private capital mobilized – to music coming from an amplifier that has four dials, that can all be turned up or down. If one or more are turned to zero, no sound comes out at all. The more the four dials are turned up, the more sound comes out.

This can also be likened to a mathematical equation, where the outcome (the level of private capital flowing towards SDGs) is a function of four variables: (1) the supply of bankable projects, (2) the risk mitigation capital that is used, (3) the links between the development banks (DFIs and MDBs) and the private sector investors and, finally, (4) the orientation of private investors towards this kind of investing.

The four break-out groups in the symposium each discussed one of the barriers; the first article, that can be found here, described the take-aways from the discussion in the first group, about Supply of Bankable Projects: “Bankability”.

This article describes the takeaways from the second group, on Risk Mitigation Capital Used, or in other words, “Concessionality”. Future articles will discuss the third and fourth barriers (“Marketplace” and “Mobilization”).

The discussions in this group focused on the barriers to increasing the ‘leverage ratio’: the multiplier of concessional capital, that is to say: how many private sector dollars can be mobilized for each dollar of public or philanthropic capital made available. The group also delved into the possible role of widely available risk data to increase the efficiency of scarce concessional capital. Finally, it asked the question of why guarantees are used relatively rarely and what could be done to have MDBs and DFIs deploy these instruments more often (we’ll refer to MDBs and DFIs as “development banks” throughout this article).

The majority view was that the public sector is unlikely to materially increase the pie of concessional capital they make available, given the prevailing economic and fiscal pressures. All the more reason, therefore, to take a harder look at increasing the efficiency of the concessional capital that is available, and at what would motivate the providers of such concessional capital to do so.

Development banks were established and organized to efficiently raise large amount of funds at competitive rates via capital markets, based on their high credit ratings derived from the paid-in and callable capital on the balance sheet coming from their sovereign shareholders. This is important blending and leverage in itself for sustainable development.

But at a transaction level, development banks often achieve lower than average (less than 1) leverage in their private capital mobilization since they are primarily incentivized to deploy capital, and not to achieve high multiplier ratios in engaging private sector capital. This is an important takeaway from the discussion: by incentivizing their staff differently, development banks could in a relatively simple manner mobilize a significantly higher amount of private capital to work for them.

It was also recognized that not all concessional capital is created equally. In the pecking order of concessional capital, the most highly prized is the first-loss equity tranche. The more first-loss equity gets provided, the higher the leverage that can be accomplished: the more private capital that can be brought in. Also, more and more philanthropic capital is entering this space. But foundations often get hit up by development banks to prop up their own concessional capital needs, especially in climate and energy transition, even though some development banks themselves have access to ample sovereign donor funds that can be tapped for concessional capital.

Some private sector voices argued that foundations appear to have become the more sophisticated investors in blended finance compared to development banks, in light of different incentives to make and move markets. Sometimes, different development banks can also undercut each other: with too few bankable deals going around, they all wish to pile into the same deals at the most favorable conditions. More coordination between development banks would therefore be desirable, and more work on creating their own bankable deals (as was also observed in our first break-out group).

Another observation was that development banks often “originate to hold”, versus “originate to distribute” which – while understandable based on how they are incentivized – is not conducive to bringing more private capital towards sustainable development projects. In other words, development banks should do more “moving” than “storage” of development financing.

Generally, there is an observable trend that concessional capital is moving away from pure grants toward repayable grants (i.e., interest-free loans, to enable re-deployment of the grants so returned), and often toward structures that seek some modicum of return. This is often obscured by concessional capital getting pooled from different sources and with different characteristics.

Generally, the conclusion was that development banks are providing the most effective blending tools – with higher mobilizing power – least, and the least effective blending tools – with lower mobilizing power – most. As observed above, reversing this requires updating incentives, as well as better education on deploying those more effective tools (that also tend to be more complex), and finally a clearer mandate from governments (development banks’ shareholders) to accept higher levels of risk on their balance sheets.

Turning to the possible role of widely available risk data to increase the efficiency of scarce concessional capital, the consensus was that the public release of granular data on delinquency and default in emerging markets transactions, currently held for the benefit of development banks only in the GEMS risk database, would make a major difference for the private sector investors when they assess relevant risk factors and try to size concessional tranches efficiently. Currently, risk data is not available or incomplete, and hence concessional tranches get sized conservatively (i.e., inefficiently) and based on mere rules of thumb.

This Global Emerging Markets Risk Management database, managed by EIB and IFC, holds a treasure trove of several decades’ worth of comprehensive emerging markets risk data, by sector and market. It was generally felt that GEMS is a public good that should have been made available to private sector investors a long time ago. The release has been worked on for several years, and the break-out group noted that it might finally see the light of the day in 2024, which would be welcomed.

It was also recommended that development banks should have different KPIs. Despite the ubiquitous Non-Disclosure Agreements, there should be disclosure clauses for certain key metrics of projects. Ex ante assessments often get done meticulously, but often they are not evaluated against ex post outcomes. The feedback loop to learn from successes and failures is often inadequate.

Lastly, on the topic of guarantees, according to OECD rules on Official Development Assistance (“ODA”), guarantees are counted as ODA when they are called upon and paid out, not when issued. This is a major disincentive for the public sector, including development banks, to use guarantees more often. However, it was noted that certain government agencies (such as USAID and SIDA) form the proverbial exception to this rule.

Global templated off-take guarantees have been designed but failed to gain traction or did not get implemented. As a consequence, guarantees, if and when issued, are usually highly bespoke, which is not efficient for the market as a whole and its participants. Foundations are often asked for guarantees, but because they are non-rated entities, they would have to be fully cash-collateralized which, again, is not efficient and therefore not used.

In sum, under the header of “concessionality” there are a number of barriers that need addressing, but as the group discussion summarized here shows, these are barriers that can be overcome.

But there are more bottlenecks and our next articles in this series will therefore focus on the third and fourth dials in our framework: Links between MDBs/DFIs and the Private Sector (“Marketplace”) and Private Investor Orientation (“Mobilization”).

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Michael Wright

Agriculture · Environmental Sustainability

Vincent Ruinet

Power Grid · Power & Utilities

illuminem

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

World Economic Forum

Carbon Removal · Sustainable Investment

UNEP FI

Circularity · Sustainable Investment

Financial Times

Oil & Gas · Sustainable Investment