Procurement of Innovation and the green transition, two allies

· 19 min read

In Europe, public expenditure on works, goods and services constitutes approximately 14% of the EU's GDP, which corresponds to approximately 1.9 trillion euros per year, 500 billion of which are allocated at the EU level. This amount is a potential to be exploited to stimulate the demand for innovative, green and digital solutions to accelerate the transition by strengthening the competitiveness of European industry, in particular of small innovative companies, writes Ivo Locatelli [1], Senior Expert of the European Commission, in this article that also illustrates the main initiatives of DG GROW (European Commission) on the subject.

The second edition of the “European Innovation Procurement Awards" (EUIPA) 2022 has been launched, building on the first edition’s success, to recognise the efforts done by public and private buyers to promote and implement innovation and green procurement across Europe.

Arvea Marieni, one of illuminem’s Energy Voices, is a high-level expert for the European Innovation Council (EIC) and was the rapporteur and a member of the jury for the category strategy of the EUIPA 2021. In addition to this, she contributes – in dialogue with the Commission - to the definition and uptake of climate and environmental KPIs for public procurement, focusing on BIM and Digital Twins in public works to improve value for public money, quality of the public estate and for the sustainable competitiveness of industry.

Public procurement is the purchase by governments and state-owned enterprises of goods, services, and works. It accounts for a significant amount of total (central and sub-central) government expenditure and is possibly the largest spending item of the State together with salaries and pensions. Public demand is particularly important in sectors such as transport and mobility, education, office equipment, construction, health, and defence.

In the EU27, government expenditure on works, goods and services represents around 14% of EU GDP, accounting roughly for 1.9 trillion euros annually – 500 billion of which are published at EU level representing 3.5% of the GDP. This is an untapped potential to stimulate the demand for innovative solutions, notably for innovative small businesses.

The 2014 public procurement directives adjusted the public procurement framework to the needs of public buyers and economic operators arising from technological developments, economic trends and increased societal focus on sustainable public spending. Public procurement rules are no longer only concerned with the tender process (“how to buy”) – they provide scope for incentives on the outcome (“what to buy”), taking into account objectives such as green, innovation, social.

The centrality of public procurement is indisputable. In several economic sectors, public buyers are the predominant players on the demand side. These sectors generate a high value-added and impact significantly on the upstream fabric. At the same time, these sectors are at the heart of key societal challenges such as an ageing society and welfare, building an EU defence and sovereignty, green and digital transformation, etc.

The public sector and innovation suppliers could grasp this opportunity to offer new and often undiscovered avenues to provide better and more efficient public services making use of new technologies or solutions to face those societal challenges.

Relations between public procurement and innovation can be very broad and encompass different dimensions. Public services in need of new solutions are users of innovation and benefit from it; moreover, the public sector contributes by influencing innovation. Finally, innovation can be applied to how public procurement itself is organised and run by public administration.

Procuring innovation is public procurement aimed at purchasing innovative solutions. Innovative solutions may be new or highly improved products and services, but also new ways of working and organizing. In short, a public buyer describing its need in a functional manner and not a detailed one would leave space for innovative solutions from the market. This leaves room for businesses and researchers to develop innovative products, services or processes (or a combination of all of those) to meet those needs. Therefore, the public buyer, instead of buying off-the-shelf, acts as an early adopter and buys a product, service or process that is new to the market and contains substantially novel characteristics. Procuring innovation early in the development process can contribute to speeding up the diffusion of innovation in the market.

On the business side, innovation activities vary greatly in their nature from firm to firm. Some firms engage in well-defined innovation projects, such as the development and placing in the market of a new product, whereas others primarily make continuous improvements to their products, processes and operations.

The advantages of innovation procurement are manifold: addressing an arising need, accelerating the diffusion of innovation in the market, boosting the economic recovery, the green and digital transitions and the resilience of the EU, modernising public services, helping start-ups and innovative firms, delivering higher quality public service on an optimal budget.

Two other dimensions are worth noting. First, public procurement of innovation is essential for the public administration to carry out its core functions as it is so enabled to deliver services to citizens or business. Everywhere budgetary constraints point public administration towards identifying solutions to maintain and improve the delivery of public services using fewer resources, while addressing new societal challenges and public goals. In this respect, and looking at it from the perspective of public use of the results, public procurement of innovation seems to have an advantage to other policy tools available to promote innovation (grants, subsidies and tax incentives). In fact, in the case of procurement of innovation the outcome remains available to the public for use by citizens.

Secondly, it is interesting to see how businesses perceive the technological push impressed by the State via public procurement. The Executive Opinion Survey of the World Economic Forum [2] includes an indicator of demand conditions for innovative products. This is proxied by business perception of government procurement of advanced technology products (graph 1). Data suggest that in Israel and the US, the State is seen as a source of innovation for the rest of the economy (via defence and NASA in the US), or in China in relation to the political/economic model of the country. However, in the EU, business does not seem consider public procurement as an engine of innovation.

![Graph 1: Business perception of government procurement of advanced technology products. Source: Source: own elaboration from World Economic Forum data [3]](https://illuminem.b-cdn.net/articlebody/4679b2c30a3c42e4d58e754c6a0175d3cc8cfa8c.png)

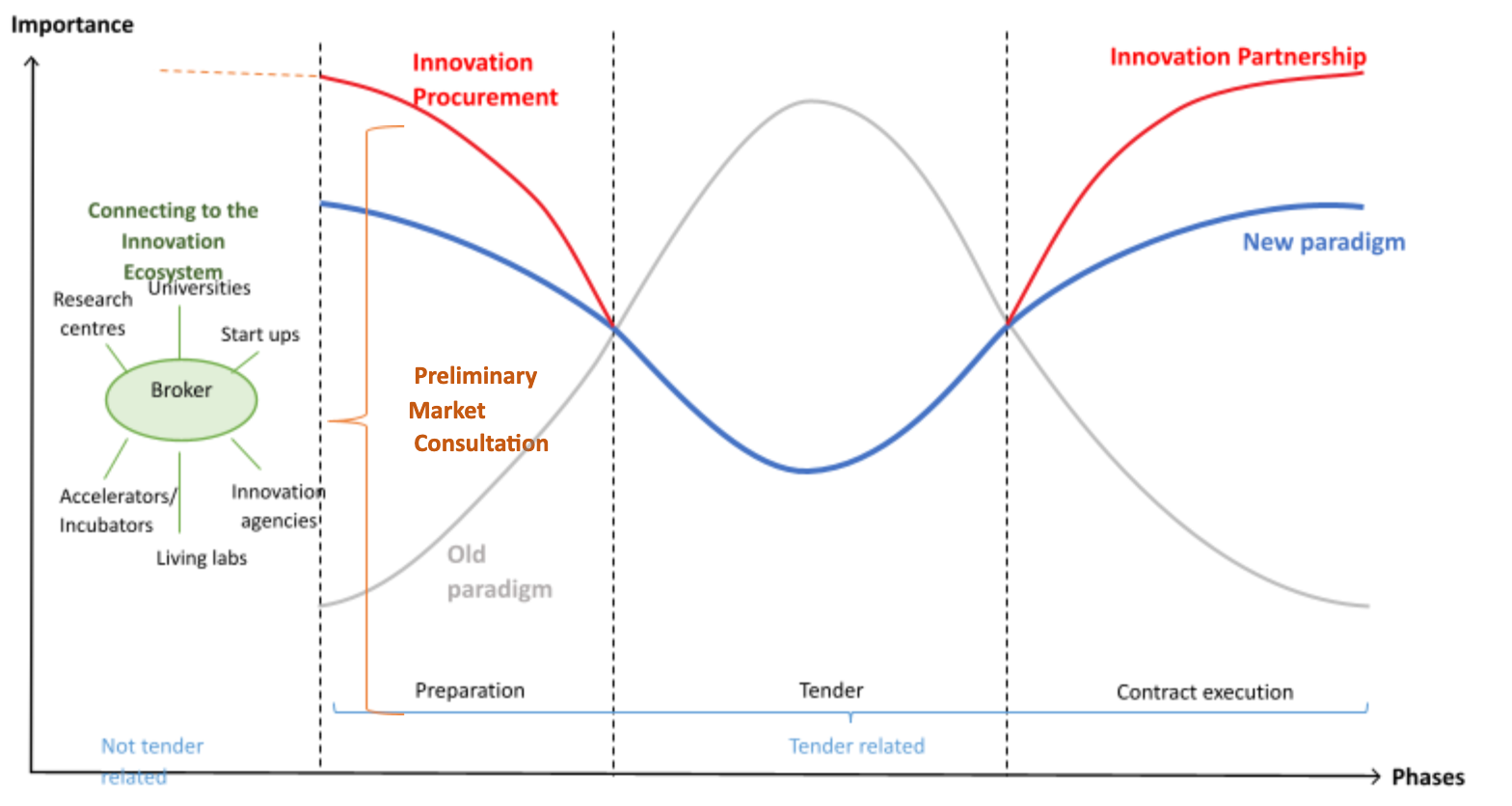

Procurement is often seen as a transactional and administrative rather than a strategic activity. To overcome this tension, a change of paradigm and focus has become necessary. Firstly, the focus is to shift from a paradigm centred on (control of) legal compliance of the tender procedure to outcome-based procurement (while obviously respecting the legality of the procedure and adherence to the principles of fair competition transparency, non-discrimination, etc.). Secondly, the change of paradigm is reflected in which phase to place the effort of the procurement process. In the new model, more attention is to be given to preparation and contract execution, than to the tender phase (see graph 2 below). Thirdly, public procurement is not to be understood as a linear process, but rather as loop, with the evaluation feeding future procurement projects.

Early engagement with suppliers has been historically considered a risky activity in terms of corruption. However, too formal relations and too little contact in pre-tender preparation with the suppliers increase possible difficulties. So, engaging with the suppliers in tender preparation is a de-risking element. In fact, buyers who have carried out a thorough market consultation report a lower level of legal challenges.

When dealing with procurement of innovation, the preparation phase becomes even more important. The Innovation Partnership (IP) requires stronger care in the execution phase than a traditional procedure. The IP allows buying in one go the R&D (research and development) / innovation and the resulting innovative goods or services. This implies that the solution is developed during the contractual relationship between the buyer and the supplier [4]. This is needed since the public procurement process itself does not provide an optimum environment for the development of innovation, the latter requiring enhanced flexibility, cooperation between parties and negotiation.

The relation with innovation ecosystems is crucial for this procurement, as they are the main source of innovation in a rapidly transforming world. Although it may not be easy to bring together start-ups and public purchasers who tend to speak different languages, it is necessary for buyers to be able to anticipate the future and know who generates value. Industries are changing very quickly and there is a risk in not engaging with the market; a buyer who does not understand the market is inevitably more vulnerable to the seller. Preliminary market consultation provides buyers with essential insights on what the market is ready to offer within the buyer’s budget and timeframe. Consequently, it is a pillar for drafting the appropriate technical specifications, for the negotiation, and choosing the most appropriate procurement approach and procedure to purchase innovation via procurement.

By connecting to the innovation ecosystem, buyers can identify and interact with key innovators, such as academics, research centres, living labs, start-ups and innovative companies, accelerators and incubators, brokers or even crowd-solving problems platforms or citizens themselves to propose solutions to urban/educational/ etc. challenges. Also, organising hackathons can help with generating ideas to solve real-life problems.

The buyers’ relation with the ecosystem is not necessarily tender related, but rather a continuous/regular communication between public authorities, service providers and innovators. An intermediate body – the broker – could certainly facilitate the job of the public buyer in diffusing knowledge created in the ecosystem. The degree to which the public sector can interact with private and other actors of the innovation ecosystem is a key component of the public sector’s innovation capacity. This may require a management change and a revisited approach towards innovation, and procurement itself. Considering innovation ecosystems only close to business environment is a false myth. The ecosystem may be led by the government itself for sectors that are more naturally driven by public institutions (healthcare, defence, etc.). So, dynamic public administration and science links are in need just as much as science-industry ones.

Procurement of innovation may turn into developing something new. In 2016 electric articulated buses were not available. In this context, Rennes Metropole in France launched an innovation partnership to develop a 100 % electric articulated bus, and to adjust standard electric buses to the operating methods of its transport network.

Procuring innovation may also imply replacing the existing solution with something completely different. The Ministry of Health in Portugal wanted to optimise the operation of the car fleet. Instead of buying new cars, it decided to buy a digital platform where the information related to the use of the car fleet (vehicles, routes) would be centralised. The platform resulted in a reduced number of vehicles, lower costs (e.g. insurance, fuel, etc.) and environmental impact.

In some cases, procuring innovation can have far-reaching effects in terms of technology development and include R&D. For instance, Tallin Public Utility (in Estonia) run a public procurement procedure for the development and deployment of road surfaces producing solar electricity. In another case, the purchase meant a significant investment for the public purse (1,2 billion euros), and a huge technological challenge (development, maintenance and delivery of battery trains to rail on non-electrified train lines). In this case, the buyer was the Ministry of Transport and Economy of Schleswig-Holstein in Germany.

Public financing of R&D&I (research, development and innovation) can take two forms: direct funding through instruments such as grants or public procurement, and indirect support through the tax system. The latter case is well known as over time, more and more countries have introduced R&D tax incentives. In the EU, 21 States were offering R&D tax relief in 2018, a significant increase compared to only 12 in 2000 [5]. Also, the budgetary allocation of R&D subsidies is publicly available.

In contrast, there is very limited robust statistical evidence on the link between public procurement and innovation. To build knowledge on actual use of procurement of innovation, the Commission services have carried out an assessment of one specific but important procurement procedure, the IP [6]. The IP has been introduced in the EU legal framework of 2014. It allows to combine research, innovation, and the procurement of an innovative and tailor-made solution not available on the market in one single procedure. It also leaves room for negotiation and co-creation between the supplier/s and the public buyer. For the supplier, one of the key assets of the IP is that it includes a purchasing commitment in case of success and re-use the innovation in other projects; for the buyer, it allows affordable access to innovative technology. Due to its novel approach, it is little known across buyers.

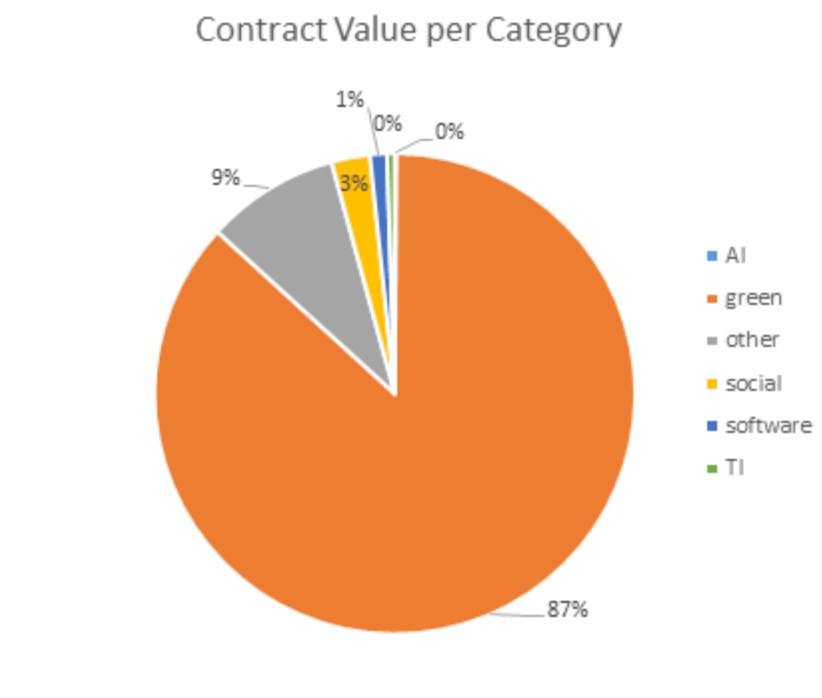

In the period of 2016-2020, 7.8 billion euro have been invested to develop and then purchase innovative solutions using the IP, corresponding to 103 contracts awarded in the EU27 and Norway. In terms of value, 87 % went to green innovation and green technologies alone [7]; about 100m of contract value was awarded to develop artificial intelligence (AI) or software, while double this amount (203m euro) of contract value was awarded for social purposes (see graph 3). In terms of sectors, the highest number of contracts went to environmental projects, followed by construction and mobility. As regards the contracts awarded to SMEs (in the case of start-ups the public buyer is often the ‘first customer’), the data are noticeable. About 2/3 of contracts have been awarded to an SME and or a consortium including an SME and this is growing over time; in value terms, this represents over 41% of the total value of contracts awarded in the period 2016-20 conducting an IP.

The data refer to one specific procedure, and this is indeed a limited share of procurement of innovation. The total value of procurement of innovation, all type of procedures and tools (e.g. competitive dialogue, competitive procedure with negotiation, open procedure, use of variants, etc.) is certainly much higher. Although they cannot be easily generalised to the full public procurement, a few initial conclusions can be drawn.

Steering innovation through buyers’ communities. Procurement of innovation helps the green and digital transformation of cities, regions, hospitals, etc. The Commission’s project “Big Buyers for Climate and Environment [8]” is based on a simple idea: connecting public buyers to each other to share know-how on markets and procurement and create a purchasing volume which could drive the market towards innovative solutions. A collaborative approach with the innovation ecosystem and joint market dialogues are the foundations of this approach. Combining the purchasing power of individual public entities and bringing them together in strategic partnerships leads to lower costs, helps the introduction of innovations into the market, and help scale up good solutions. At the same time, it allows buyers to improve capacities in professional procurement practice. This also helps overcome the fragmentation of public procurement, with many public buyers facing similar or the same needs.

One of the workstreams of this project concerns achieving a zero-emission construction site. Conventional construction works are important sources of pollution. The construction industry contributes 23% of the world’s CO2 emissions across its entire supply chain, and approximately 5.5% of these emissions come directly from activities on construction sites—predominantly through the combustion of fossil fuels to power machinery and equipment. The Big Buyers project has put cities work together to develop and pilot innovative sustainable procurement approaches to reduce the environmental impact of construction activities and encourage market innovation. Using tender award criteria in a coordinated and targeted manner across public construction projects is sending a strong signal to the market, driving innovation and low-carbon transformation. The market response has been positive, with several machine retailers stepping up to provide tailor-made heavy-duty electric equipment currently not available from the suppliers.

In 2020, fully fossil-free construction sites debuted in Oslo, then followed by Copenhagen, and Helsinki. Amsterdam and Vienna are in the process of identifying suitable pilot sites to have their first fossil- and/or emission-free construction sites. Emission-free machines using electric motors are more expensive upfront compared with conventional options, but fuel savings, reduced maintenance, lower repair costs, and, in some instances, added productivity, may offset that initial investment. The other challenge is to ensure a steady supply of power to operate the electric machines.

Similar patterns of demand-driven innovation towards green or digital objectives are taking place in other areas, such as heavy-duty electric vehicles for waste collection and street cleaning, and data management for the health sector. Participants include Lisbon, Riga, Köln, Bordeaux, utilities from Madrid and Berlin, the Ministry for Health in Malta or the Greek Health Central Purchasing Body. Inspired by this initiative, Finland and the Netherlands have created national Big Buyers groups, while Canada is considering it.

The Commission plans to extend this work and scale it up to include new workstreams. On top, it is planned to set up a digital platform to facilitate cooperation, diffusion of knowledge and establishing synergies with other relevant projects. Innovation and co-creation go hand in hand and must be supported by appropriate tools. Therefore, the platform should support these two objectives and help in building up communities around specific topics (e.g. purchase of AI).

Creation of knowledge and competence: On 15 May 2021, the Commission has adopted the new version of the Guidance on Innovation Procurement [9]. The Guidance has been enriched with new sections on Intellectual Property Rights, preliminary market consultation, connecting to the innovation ecosystem, state aid, and good practices to attract innovators and innovation (many cases illustrate the purchase of renewable energy, green vehicles, water quality or consumption, etc.). This is complemented by practical tools to help public buyers. This has been accompanied by several webinars aimed at presenting and discussing specific aspects of the guidance. Another project concerns the development of “standard” contract clauses for the purchase of AI, ensuring the respect of transparency, integrity, and accountability. Finally, a methodology is being developed to estimate the price of innovative solutions before they are developed. This should contribute to reducing buyers’ uncertainty on this specific point.

Funding to develop innovative solutions. In 2021, in the Commission there were over 40 ongoing initiatives covering both procurement of innovation and pre-commercial procurement (PCP) [10] with a total estimated budget around 100m euros. Historically most of the initiatives have been allocated to PCP; however, in recent years, procurement of innovation is gaining traction. The areas covered include energy, health, security, mobility, and green and IT technology (e.g. to support the development of the EU blockchain Service infrastructure [11]) as well as horizontal ones. Many of those projects are related to the development of green technologies. One of the most remarkable is the European Innovation Procurement Award [12], which in its first edition attracted a high number of proposals. Under Horizon Europe, several pillars include calls supporting innovation procurement. This is the case of Pillar 3 (Innovative Europe) conducted by the European Innovation Council [13] (EIC). The EIC will put in place a set of measures aimed at stimulating innovation procurement and building capabilities among the innovation ecosystems’ stakeholders. Projects have also been funded to design the business model of a broker to bridge the gap between buyers (expressing innovative needs) and the innovation ecosystem.

Improving monitoring of procurement of innovation is pushed via the eForms [14], the new standard forms used by public buyers to publish notices on TED. The eForm will be implemented by Member States’ administrations from October 2023. Through automatic pre-filling, eForms will reduce the administrative burden for buyers, increase the ability of governments to make data-driven decisions about public spending, and make public procurement more transparent. The eForms will include an optional field where public buyers can indicate that they are purchasing innovative, green or social goods, works or services though the procurement procedure. The new eForms are the backbone of the forthcoming data initiative for public procurement data and the procurement data governance framework [15].

Internal coordination between all the relevant areas is ensured via an ad hoc group. This allows for synergies to be found and exploited between the different initiatives and identify gaps and opportunities for intervention.

Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

1. Senior Expert, European Commission. The views expressed in this paper are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Commission.

2. WEF’s Executive Opinion Survey annually asks more than 14,000 business executives in more than 140 economies about their perception of the capacity to innovate by firms in their country.

3. Data extracted from the country profiles included in the European Innovation Scoreboard.

4. Possibly the name “Innovation Procurement Partnership” would have been clearer and show a better link to the purpose of the partnership.

5. European Innovation Scoreboard 2021.

6. The analysis is based on contract award notices published in Tenders Electronic Daily (TED), the online portal which publishes around 520 000 public procurement notices per year, worth more than €420 billion.

7. This data is heavily affected by two large mobility projects (railways). However, even not taking them into consideration, projects with green objectives would count for 13% of the total in value and 25% of the total number of contracts.

8. https://bigbuyers.eu/

9. https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/45975

10. PCP is an approach to buy R&D services prior to commercialisation and is outside the scope of the Public Procurement legislation. R&D can cover activities such as solution exploration and design, prototyping, up to the development of a limited volume of first products or services in the form of a test series.

11. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/funding/call-tenders-eu-blockchain-pre-commercial-procurement

12. https://eic.ec.europa.eu/eic-funding-opportunities/eic-prizes/european-innovation-procurement-awards_en

13. https://eic.ec.europa.eu/index_en

14. https://ec.europa.eu/growth/single-market/public-procurement/digital-procurement/eforms_en

15. These initiatives are included in the Commission Communication of “A European strategy for data” of 19.2.2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/communication-european-strategy-data-19feb2020_en.pdf

C. Bason, Leading Public Sector Innovation. Co-creating for a better society. Policy Press, 2018

European Commission, Guidance on Innovation Procurement, C(2021) 4320 final, 18.6.2021

European Commission, European Innovation Scoreboard 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/46013

European Commission, Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, Study on the measurement of cross-border penetration in the EU public procurement market: final report, Publications Office, 2021. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c7fcd46a-b84d-11eb-8aca-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

M. Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State. Debunking Public vs Private Sector Myth. Penguin Book, 2018

P. Smith, Bad Buying, Penguin Business, 2020

World Economic Forum, The Global Competitiveness Report SPECIAL EDITION 2020 How Countries are Performing on the Road to Recovery, 2020; https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2020.pdf

World Economic Forum, Bridging the Gap in European Scale up Funding 2020.pdf https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Bridging_the_Gap_in_European_Scale_up_Funding_2020.pdf

illuminem briefings

Carbon · Environmental Sustainability

illuminem briefings

Carbon Regulations · Public Governance

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

Politico

Climate Change · Agriculture

UN News

Effects · Climate Change

Financial Times

Carbon Market · Public Governance