· 16 min read

I recently had an extraordinary and rare experience, as an academic, activist and citizen: I participated in a victorious movement. Doing this upended most of what I thought I knew about how change happens in the world, and it seems very important to share these insights with you, despite my rather embarrassing ignorance in psychology, sociology, politics and many other fields of expertise relevant to this topic. Our world has never needed more fundamental and urgent change, and you, the person who is reading this, can and should be part of making this change happen.

What I learned is the following:

- Individuals are everything;

- Institutions, alone, are nothing;

- Social pressure works;

- Urgency begets creativity (and effectiveness);

- A culture of love wins the day;

- We only understand what systems are made of when we try to transform them.

Meet the activator: Guillermo Fernandez

Guillermo Fernandez is both extraordinary and ordinary. He is a Swiss IT project manager and father of three. He doesn’t belong to any party or activist group. But he did something extraordinary: he sat down on August 9th 2021 and read the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report which had been published the day before. But he didn’t just read: he allowed himself to feel and imagine what the projections in that report meant for his children. That day turned his life upside down, and he decided he needed to act. He decided to go on unlimited hunger strike for climate on November 1st, the first day of the COP26 conference on climate. His demands were modest, but also unprecedented, not just in Switzerland, but perhaps in the world: to have climate & biodiversity scientists meet with the entire Parliament, in an extraordinary session, to be informed about the full extent of the climate & ecological crises. And, after 39 gruelling days without food, in the cold and harsh conditions on the Bundesplatz in front of the Swiss Parliament in Bern, Guillermo won.

I played a small part in Guillermo’s campaign and victory. Others did far more. But what I was able to do, and saw others do, completely upended my understanding of how we are able to create moments and movements of change. I want to share some core insights with you, then explain how and why they go against deeply engrained theories of change, which we generally base our strategies on.

First insight: individuals are everything

Individuals make change happen.

This was the biggest shock to me, and also the fact I need you to grasp the most strongly, because it holds so much promise. Individuals, starting with Guillermo, obviously, made change happen. And one reason it worked was because Guillermo, as an individual person, appealed to us as individual humans. Faced with his action and his challenge, each of us was compelled to make a choice: step up, or look away. Many people chose to look away, but a few, just enough, chose to step up and join his struggle. Guillermo called this the theory of dominoes: one domino can cause a few others to fall over, but each of these can act on others, and so on until the whole area around has been forever transformed.

At each step, in each sphere, one or two individuals, rarely more, took it upon themselves to expand and activate what they could.

These individuals harnessed their social connections, friends, neighbours, colleagues, and talked and pushed and strategised to get that network to help with the campaign. I did it in the sphere of Swiss climate & biodiversity scientists. At each step, I was not certain I was doing the right thing, but in the end each step built on the previous one, until we too were part of the large number of dominoes pushing to change the whole area.

A couple of politicians (ultimately a group of 4 formidable young women Green Parliamentarians) did the same for the Swiss Parliament. Seasoned and novice campaigners helped Guillermo with website and media support, creating leaflets, petitions and gatherings to support him, as well as building a movement of people committed to volunteer and help. A couple of people with NGO connections helped harness the support of their organisations. In each case, one or two or three people took it upon themselves to be reasonably relentless in pushing this campaign forward, without a pre-established plan, by hook and by crook, each in their own way. And those people moved mountains.

The most important thing here is that these individuals refused to be limited by the normal ways a campaign should operate, or their work or social connections should be defined. They just tried every which way to make some progress on what seemed an unsurmountable and impossible challenge.

They strategised together, sometimes came up with good ideas, sometimes with bad, tried everything. They woke up in the morning determined to do a few things to push the campaign forward, and ended the day thinking of more for the next.

They made it happen, and you can (and must) too.

Second insight: institutions, alone, are nothing

This is the corollary to the first insight, and it came as a bit of a shock, quite honestly. On the ‘left’, broadly speaking, we tend to put a lot of faith in social structures, organising and organisations, and much less in individuals. This experience flipped that understanding on its head for me.

Quite simply put, almost every organisation and institution that had a mandate to do the things we wanted to do not only failed to help us, but were often actively hostile, even trying to stop us every step of the way. That came as a nasty surprise, but we were able to overcome their resistance thanks to the strong bonds between individuals created across the political/science/activist domains during the campaign.

Some organisations (or, once again, individuals within them) were great, from the start providing space and support for the campaign to exist. In particular, one person and their organisation stepped up in an extraordinary way, working around the clock behind the scenes to make the campaign a success. But that story is theirs to tell when they are ready — even now, they are still battle-weary, and resting up.

However, as the campaign gained steam and our pathway to victory became clearer, these very same institutions that were hostile had a core role to play in legitimating the victory. So despite these institutions being hostile during the campaign phase, they had to be come collaborators during the victory proclamation and then implementation phase. This is a really important lesson: not to burn bridges openly, but also not to ever delegate the work to someone else, who sees their role as blocking your agenda. You need to learn, somehow, how to do the work of these institutions for them. Despite being internally hostile, they can play a hugely important protective role, and are certainly very important from a public perception point of view. It’s quite strange doing so much work for a hostile organisation to then take the appearance of credit for your hard-won victory, but in the real world, this is often how it plays out, and it’s important to be prepared for it.

Third insight: social pressure works

A hunger strike is obviously the ultimate act of social pressure. That’s how it works. Witnessing someone literally dying of hunger in public, for a cause, is unbearable social pressure. It worked on me, and on many others: it became hard to sleep, hard to do anything but think about how, somehow, I could help Guillermo win, so he could live and go back to his family.

I am not encouraging anyone to go on hunger strike. But I am encouraging you to create and respond to social pressure, and to understand our social intelligence. We humans are incredibly responsive creatures. We respond to each other — when we are addressed as individuals, especially. It is entirely possible for you, as an individual, to create social pressure on others, a pressure that they will have to respond to, in one way or another.

As stated above, I am not a specialist in any social science, but this is how I understand what I describe as ‘social pressure’ works:

1. One person speaks to another, standing as an individual with integrity and emotion, and makes a claim to that other person’s actions.

Guillermo, with his hunger strike, was putting social pressure on us. He was effectively saying to all of us: “Climate inaction is unbearable to me, unacceptable because of the suffering it will cause my children. I demand of you your time, attention and actions to change this, right away.”

2. When you put social pressure on someone else, that person will feel compelled to respond — whether they want to or not.

Because human beings are so hugely responsive to each other, living in community, and caring so much about our role and understanding of that community, we are always affected when someone tells us, with integrity and emotion, that we need to pay attention to them, and become involved in helping them.

It is what parents and carers do for their children, but it’s also, more broadly, how our entire social fabric works. Human responsiveness is not a purely negative burden, quite the contrary: helping and supporting others is a large part of how we bolster our self-worth, and it’s also how we find meaning in life. So you shouldn’t ever feel bad about creating social pressure about the climate & ecological (& other) crises, but use it as honestly and effectively as you can. [Pro tip: it doesn’t work without honesty. At all. Human beings are good at spotting dishonesty, it’s part of being extremely social communicative animals.]

3. A person’s response to social pressure can vary.

They might immediately see the validity and purpose of your claim to their efforts, and respond with a variation on “How can I help?”. This is your cue to help them strategise and figure out their most effective course of action: help them use their own capabilities, knowledge and creativity to move the campaign forward. Your role is to encourage them to become one of the dominoes who knocks even more dominoes over, to figure out how to create and amplify their own version of social pressure.

Another response is to shut down a bit and go off and think it over. To be honest, this was my initial response. But I kept thinking, and Guillermo’s actions left me no respite: I had to figure out how to act. So simply maintaining your social pressure can help people who are initially silent or hesitant to jump in and help eventually. Don’t back down, and be accepting and responsive to hesitations, since most will come around, especially if their concerns are addressed with honesty and empathy.

Another response is to respond negatively. This usually comes with a certain level of aggressivity, since (again, due to social conditioning), most people would rather respond positively than negatively to a request that puts into play their position as a ‘good’ person in society. This kind of response is also, paradoxically, a positive outcome of social pressure. You have compelled someone to respond and state their position: that is an opening, either to further dialogue (expounding on why inaction is not, in your view, compatible with them being a person in good standing in society, and enabling them to find a way to help), or, if that breaks down, or it’s more expedient for your campaign, to accountability: to expose that person as an obstacle to positive change. The later is only for people with public roles, obviously. But holding individuals to account for their responses, publicly or privately, is a core part of social pressure.

Effective campaigners and organisers use social pressure all the time to make progress in their work. The legendary labour organiser and theorist Jane McAlevey for instance highlights the importance of ‘organic leaders’, who are respected and trusted within their work and community, because if they express the need for change, people listen to them, and come to agree. You may or may not be an ‘organic leader,’ but if you speak with honesty, integrity, compassion and emotion, you will be able to change your community.

The point here is that you can exert social pressure, starting from who you are and what you know and care about. If you make your integrity and caring the centre of your claims on others, they will have a very hard time dismissing you, and will soon enough helping with your efforts, and helping you to convince others. And if that happens, one way or another, you become unstoppable.

Fourth insight: urgency begets creativity (and effectiveness)

We all know we are in races against time for the complete transformation of our societies away from trajectories of increasing harm and danger, but, for the most part, we have obligations and habits in our day-to-day lives which, alongside a culture of denial and delay, help us push that urgency to another day. Guillermo’s action of hunger strike made the urgency extremely personal (see first insight on individual action) and extremely real. It forced all of us who wanted to help him win to get off our routines, and get change done in the here and now. It was disruptive and caused us to become extremely creative and effective.

The challenge is how to bring that urgency and reality into our daily lives, as a constant.

We can move mountains when we know the clock is ticking, and we need to make immediate progress. We take risks, we cut corners, we reach out to each other, we get things done. One of my core resolutions this year is to hold on to that urgency, to remember that even if Guillermo is not, thank goodness, still sitting out in the cold & wet with no food, there are others who demand my attention and help, even if I don’t see them with quite the same clarity. That urgency has to become part of our daily lives, which is how we will transform our governments and policy-makers to emergency-mode as well.

Fifth insight: a culture of love wins the day

This one is difficult for me, because I am a (recovering?) rage and negativity monster. But Guillermo is very different, and we can learn from each other. Practically the first thing he told me, when I went to Bern to sit with him for a couple of hours early on in his hunger strike, was “My greatest character fault is my jolly disposition.” And I came to learn this was quite close to the truth.

Guillermo always had a smile and a kind word to all those who came to see them. People often came, desperate and in tears, because they shared his great fear of the unfolding climate crisis and government inaction, and were also worried about him and his health. There were often shared tears, but always compassion, and Guillermo always left everyone with a sense of fun and joy. He might have been dying, but he still enjoyed people’s company and exchanging thoughts and feelings with them. His movement grew through the support of activists who ran empathy circles, where everyone was welcome to express their grief and concern — and then activated to work on changing it.

I still don’t know how exactly to make it work or unlock that key, but the fact is that the vast majority of humanity shares concern for each other, grief when others are hurt, fear when others are in danger, and wants desperately to be able to help protect and support others, even if we are often paralysed by the hugeness of the task, or our ignorance about how exactly we can help. So here, the point is to be kind. Listen and make space for the love, grief and fear that so many of us feel at this time, and then make even more space to help those people to grow into their activism. Help them see themselves and each other as agents of change, who can do so much to protect and support each other. This is what love looks like.

Sixth insight: we only understand what systems are made of when we try to transform them

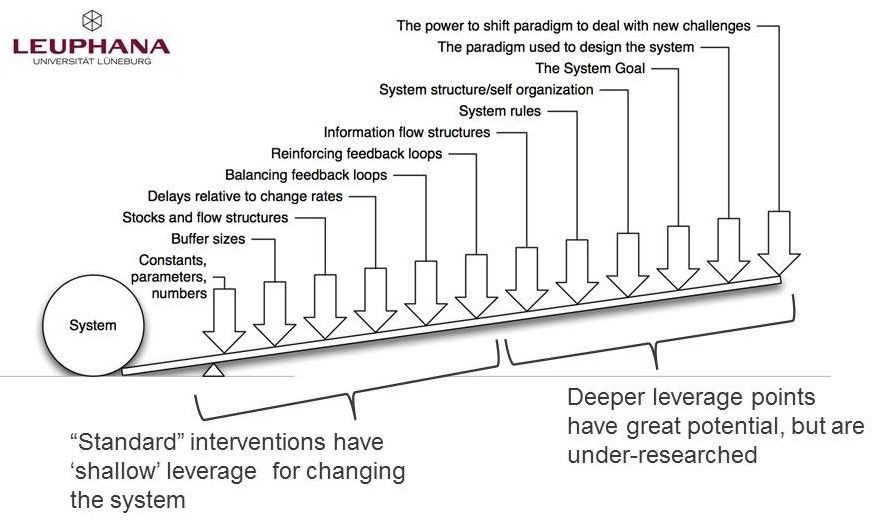

This point is a bit more theoretical, and combines my experience and the writings of the pioneering systems theorist Dana Meadows especially. If you haven’t yet read “Leverage Points: places to intervene in a system,” do yourself a favour and go read it now. In this piece, Dana explains that different types of intervention have more or less potential to change systems, with some intervention points being more shallow (for example changing single parameters within systems), and others much more powerful (for example changing system structures or goals and operating paradigms).

Because we desperately need transformative change to avert the worst of the climate and ecological crises, we want our activism to be effective on the deeper leverage points: the rules, structures, goals, and design paradigms of the systems that surround us. And in order to do that, we have to have some idea of how those systems work to start with. But here’s the problem: we usually have absolutely no idea how the systems that govern our daily lives really work. Not the foggiest.

It takes activism and active confrontation with systems to really understand what they are made of, how they work, and how to change them.

We often think we understand the systems that make up our societies. We have history, civics and economics classes which tell us stories about how these systems work. And almost invariably, these stories are fairytales. They do not correspond to reality at all. Just two examples, to give a flavour of what I mean:

- We are taught that social progress against injustice is the normal arc of enlightened history: all it takes is for someone to point out the injustice, then the powers that be, supported by concerned citizens, make the system become more just. This is the liberal “information and awareness-raising” theory of change. Sometimes, it’s even known as “speaking truth to power.” According to this false fairytale, information of shocking or unjust facts is enough, somehow, to percolate through society, create awareness, mobilise concerned citizens, and shame those in power into acting. Of course, this is not the case. Information and awareness are crucial, but even more important is action: acting to mobilise, organise, campaign, be relentless forces to transform the system away from injustice. Just highlighting injustice on its own has never cut the mustard.

- Another fairytale is economic in nature: that the market delivers what we desire, and is the source of our well-being. This fairytale has been comprehensively debunked by scholars like Tim Jackson, Kate Raworth, Jason Hickel and many others, so I won’t rehash the arguments here. But I do want to explain how paralysing this fairytale is in terms of transforming our economies. It stops us from acting, because the belief that we create the market via our consumer desires means that we see ourselves as culpable, like in a distorted funfair mirror. It leads people to build campaigns around “voting with our dollars,” rather than target the large megacorps designing both production and consumption.

The core point here is that it’s often only when we confront existing systems with our actions that we understand what these system really are: how they responds to defend themselves tells us much more about what we need to do to change them. And for academics, this particularly hard, because we are used to theorizing. Those theories are helpful, sure, but confrontation with reality is the best teacher here. So don’t sit back and read and think and wait for to have achieved the perfect theory to develop the perfect strategy for action: get out there. Interfere. Talk to people. Try like all heck to change bits and bobs of the systems that surround you. As you’ll try, you’ll learn, and as you’ll learn, your chances of success will expand extraordinarily.

This article is also published on the author's blog. Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.