Hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector (I/II): US decarbonization strategy

· 35 min read

Co-author: Raqib A. Chowdhury (M.S. Candidate in Energy Policy and Climate. The Johns Hopkins University)

Hydrogen (H2) presents a vital opportunity for decarbonizing the road transportation sector in the United States. Since the United States has the world’s largest economy, its decarbonization is essential for attaining global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction of the magnitude needed to fight climate change. Such efforts need to be undertaken on the federal, state, and municipal levels. Decarbonization is broadly defined as the decrease in the carbon intensity of an economy (Meyer, 2020). The Kaya Identity equation describes carbon intensity as carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions/energy. The Kaya Identity relates the global CO2 emissions to population, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, CO2 emissions/energy (carbon intensity), and energy/GDP (energy intensity) (Andrews & Jelley, 2007).

According to Economist (2021b), “only a holistic, multifaceted approach to decarbonization is likely to succeed” (p. 12). In other words, decarbonization efforts in all sectors of the economy can help address climate change. Due to the significant dependence on petroleum-based fuels, the transportation sector, in particular, faces substantial hurdles in lowering its carbon dioxide emissions. Gross (2020) states that the sector “is the least-diversified energy end-use sector, dominated by oil” (p. 4). For example, in 2019, petroleum-based fuels accounted for 92% of US transportation. The US transportation sector was responsible for the most significant source (28%) of US emissions versus the power sector, which contributed to a 25% share of US emissions (Saundry, 2021b). Andrews and Jelley (2007) assert that “to obtain deeper cuts in emissions will require lowering the carbon intensity of the fuels” (p. 442). Therefore, eliminating US emissions from the transportation sector will be crucial to meeting IPCC reduction mandates (IPCC, 2022) to avoid climate change.

As a valuable player in reducing carbon intensity, hydrogen may complement other low-carbon technologies and energy efficiency improvements in the US decarbonization efforts, especially in the road transportation sector. From a net-zero target perspective, the importance of hydrogen is manifold. "[While] not in itself the solution to abate all emissions across sectors, hydrogen uniquely complements and enables other decarbonization pathways such as direct electrification, energy efficiency measures, and biomass-based biofuels" (Hydrogen Council, 2021, p.13). Different factors, such as technological, infrastructural, economic, political, and standards (safety and fueling protocols) related to hydrogen deployment in the US road transportation sector, will be vital in achieving favorable decarbonization outcomes.

Hydrogen, the lightest element, is the most abundant element available in the universe. Hydrogen exists in gaseous form at normal pressure and temperature. However, it turns into liquid at minus 253°C (or minus 423°F). In the solar system, Sun consists of hydrogen and helium gases. On Earth, hydrogen exists only in compound form with other elements, such as gases, liquids, and solids (EIA, 2021). As the simplest element, hydrogen has many appealing physical properties. First, it has a high energy density by mass. One kilogram of hydrogen stores about three times (33.3 kWh or 120 MJ/kg) the energy content of one kilogram of gasoline (12.2 kWh or 44 MJ/kg). Tesla's new 4680 lithium batteries may achieve, at a maximum, 300Wh/kg. Some of the future solid-state batteries will only deliver less than 1kWh/kg, which is a tiny fraction of hydrogen's energy density by mass (DOE, 2020a: Neil, 2022). Second, hydrogen has significant environmental and health benefits. For example, hydrogen does not produce carbon monoxide or sulfates when burnt in the air except for a few nitrogen oxides. When hydrogen is used in a fuel cell (described more in Section 3), it emits nothing more than water (Economist, 2021).

Due to the lack of the elemental form of hydrogen on Earth, hydrogen has to be separated from the hydrogen-containing feedstock (fossil fuels, water, biomass, or waste materials) with an energy source (DOE, 2020a). Unfortunately, due to the laws of thermodynamics, it takes more energy to derive hydrogen than hydrogen provides when the element is converted into usable energy (Economist, 2021a, p.19). In other words, the current hydrogen production is a very energy-intensive and costly process. Depending on diverse resources and technological methods, hydrogen can be classified into black (made with coal); gray (made with natural gas), blue (same technologies with added carbon capture and sequestration (CCS)); green (electrolyzers with renewable energy); pink (electrolyzers with nuclear power); and turquoise (pyrolysis through heating methane) (Economist, 2021a). The most common "large-scale production technologies" are the following: natural gas steam methane reforming (SMR); nuclear high-temperature electrolysis (HTE); biomass gasification, and low-temperature electrolysis (LTE), which uses variable renewable energy, and gasification of coal. Other hydrogen production technologies are under development or available with different maturity levels or costs (Ruth et al., 2020; SGH2 Energy, 2022).

The current main uses of hydrogen are concentrated in the following applications: 1) as a catalyst and chemical feedstock, 2) as a chemical in ammonia (fertilizer) production, 3) in petrochemical and refinery processing, and 4) as a hydrogenating agent in drug and food production. Like electricity, hydrogen can be used as an energy carrier (fuel) to move, deliver, and store energy from other sources (DOE, 2020a). Presently, hydrogen is not widely used as a fuel but has enormous potential to emerge as a low-carbon fuel option for electricity generation, manufacturing, and transportation sectors (DOE, 2020a; EIA, 2022).

This study focuses explicitly on integrating hydrogen, as an energy carrier, into the US road transportation sector. It primarily focuses on medium-and-heavy-duty vehicles, which travel long distances (regional/intercity buses, trucks) and light-duty vehicles (light-duty trucks and high-utilization rate passenger cars, i.e., taxis). The analysis is structured into five main sections. After the introduction in Section 1, Section 2 describes the qualitative and quantitative methods employed in the paper. Section 3 explains the challenges and opportunities of hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector. Section 4 outlines the strategy for using hydrogen in the road transportation sector as a part of the US decarbonization strategy. Section 5 concludes, addresses limitations, and offers further research suggestions. The following section describes hydrogen technology and its potentially important role in the US economy.

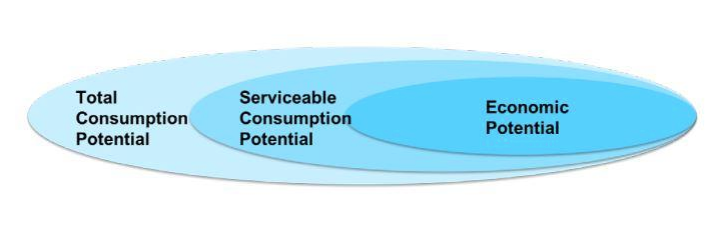

The analysis in this research paper builds upon different domestic and international case studies and quantitative indicators to present a strategy of using hydrogen in the road transportation sector as a part of the US comprehensive effort to decarbonize its economy. In addition, the paper’s methodology is informed by the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s (NREL) methods for estimation of hydrogen’s economic potential as an energy carrier, a transportation fuel for light-duty fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), and medium-and-heavy-duty FCEVs in the contiguous United States (Ruth et al., 2020). NREL uses resource analysis (Brown et al., 2016) to estimate the economic potential of hydrogen for the United States. In the analysis, economic potential represents a subsection of technical potential and serviceable consumption potential, which includes only the amount of the resource that can be sold at a profit. Technical potential, in turn, is a part of resource potential, which is constrained by the resource’s energy content and theoretical physical potential. Further, serviceable consumption potential is a subset of the total consumption potential, representing the maximum amount of hydrogen’s theoretical consumption (Ruth et al., 2020). The relationships are illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

NREL defines the economic potential of hydrogen as "the quantity of hydrogen expected to be available at prices lower than other options to meet each end-use requirement" (Ruth et al., 2020, p.12). Its researchers estimate the economic potential for hydrogen as the market equilibrium between demand and supply by utilizing microeconomic analytical methods (Brownlie and Lloyd Prichard 1963; Schwartz 2010). The researchers calculate the economic potential for every hydrogen application in the national market and find the threshold price at which point hydrogen may compete with other market options. NREL uses 2050 as the single target year for all hydrogen applications in the United States to make the analysis possible. This approach corresponds with the goals of the Long-Term Strategy of the United States: Pathways to Net-Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2050 (DOS, 2021b). In addition, the hydrogen market sizes are reported on a mass basis (in a million metric tons (MMT) of hydrogen).

NREL constructs demand and supply curves for hydrogen applications in the national market to calculate the economic potential. First, the researchers build demand curves for each hydrogen-consuming market, estimating the quantity of hydrogen every consumer might purchase over a range of prices. The light-duty FCEV’s hydrogen demand curve is obtained by utilizing the MA3T vehicle-choice model to ascertain the vehicle price, fuel price, and vehicle performance impact on consumer choices and further market penetration. NREL uses the economic equilibrium method for mature market estimations, but the MA3T model's estimate for 2050’s potential vehicle stock is not yet available for a mature market. Therefore, the researchers perform necessary changes in their approximations. Namely, NREL uses vehicle penetration when the market share for FCEVs reaches equilibrium in the MA3T vehicle-choice model (corresponding to the year 2075) (Oak Ridge National Library, 2019). The researchers then multiply the total vehicle stock in 2050 by the market share in 2075 to estimate the number of vehicles and corresponding hydrogen demand. So, the researchers calculate the equilibrium light-duty FCEV penetration if that market equilibrium could be reached by 2050 (Ruth et al., 2020).

To estimate annual FCEV demands in the demand curve estimates for medium-and-heavy duty vehicles, NREL uses the projected FCEV market shares modeled for light-duty vehicles, as described in Elgowainy et al. (2020). NREL assumes that FCEV penetrations in the medium-and heavy-duty vehicles’ markets might be similar to or exceed vehicle penetration in the light-duty vehicles’ markets due to the performance advantages of FCEVs over the battery-electric vehicles in duty cycles needed for medium-and-heavy duty vehicles (Ruth et al., 2020). NREL constructs supply curves to obtain the quantity of hydrogen each producer would supply at various prices. The supply curves are for hydrogen produced via the following production technologies, namely, natural gas steam methane reforming (SMR); nuclear high-temperature electrolysis (HTE); biomass gasification, and low-temperature electrolysis (LTE), which uses low-cost dispatch-constrained electricity from solar, wind, and nuclear generation. Such supply curves represent the summation of production and delivery costs, so, in the transportation sector, they may be considered as supply prices at the city-gate terminal for transportation demands (Ruth et al., 2020).

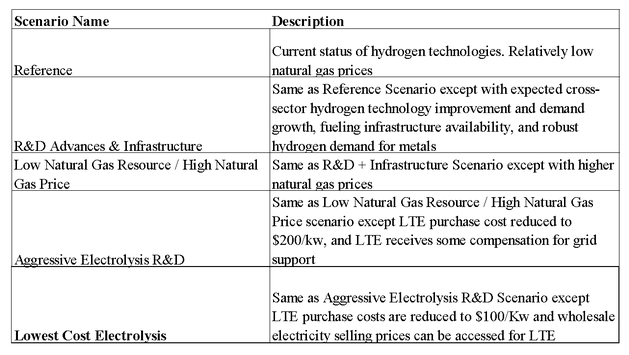

Finally, NREL develops five scenarios, which use different combinations of the demand and supply curves, to estimate the range of hydrogen’s economic potential in the contiguous United States, such as Reference; R&D advances plus Infrastructure; Low natural gas resource/High natural gas price; Aggressive Electrolysis R&D; and Lowest-cost Electrolysis. These scenarios depend on market conditions, fueling hydrogen infrastructure availability, hydrogen prices, hydrogen technology R&D, and prices that users will pay for hydrogen due to other competitor technologies without changes to the current state and federal policies. The scenarios do not include potential rebound effects when the price for competing technologies and resources change due to hydrogen's influence on their market shares (Ruth et al., 2020). Such scenarios are described in Table 1.

This study uses NREL's economic potential estimation for the road transportation sector (light-duty, medium, and heavy-duty vehicles) calculated in the most ambitious, Lowest-Cost Electrolysis scenario. NREL researchers state that "we identify the economic potentials for several scenarios but do not consider how to reach those potentials" (Ruth et al., 2020, p. 116). This analysis aims to demonstrate a specific strategy to reach the NRELs’ projected hydrogen economic potential for the road transportation sector in the Lowest-Cost Electrolysis scenario, where hydrogen is used as the preeminent tool for significant decarbonization in the United States.

Moreover, as a guide, the study uses the skeleton of the strategic framework laid out by the Fuel Cell & Hydrogen Energy Association (FCHEA) in the Road Map to a US Hydrogen Economy report. In this report, the association describes the specific roadmap for all US economic sectors, organizing it into four important phases: 1) 2020-2022 (“immediate next steps”), 2) 2023-2025 (“early scale-up”), 3) 2026-2030 (“diversification”), and 4) 2031-beyond (“broad roll-out”). Each phase has specific quantitative and qualitative milestones for all hydrogen applications. Also, every phase designates the most important strategy enablers, namely "policy enablers" as well as "hydrogen supply and end-use equipment enablers" (FCHEA, 2020, p.13).

This analysis takes a similar approach to phases and facilitators in devising a specific decarbonization strategy, which uses hydrogen deployment in the US road transportation sector. The strategy in Section 4 consists of four phases: 1) 2022-2024 (immediate steps), 2) 2025-2027 (short-term scale-up); 3) 2028-2032 (mid-term steps), and 4) 2033-2050 (long-term roll-out). The strategy facilitators are 1) policy facilitators and 2) hydrogen fuel and supply chain facilitators. Due to the lack of access to special transportation-related modeling tools, the strategy in this study primarily focuses on qualitative recommendations and provides quantitative indicators whenever possible. The next section describes the state of the current US road transportation sector along with the challenges and opportunities of hydrogen integration into the sector.

Hydrogen's deployment as an energy carrier is essential for US road transportation segments, especially for medium-and-heavy duty vehicles traveling long distances (intercity/regional buses, trucks, etc.) and light-duty vehicles (light-duty trucks and high-utilization rate passenger cars, i.e., taxis). US transportation consists of highway (road) transportation (81%) and non-highway transportation (19%). Within highway transportation (81% in total), passenger cars occupy 23%, light trucks – 33%, medium/heavy trucks – 24%, buses – 0.8%, and motorcycles – 0.2%. non-highway transportation usage (19% in total) consists of air (8.8%), water (4.2%), rail (2.1%), and pipelines (3.6%) (Saundry, 2021x). The US GHG emissions approximately correlate with energy usage within various segments of its transportation sector due to the prevalence of petroleum-based fuels. Light-duty vehicles account for 59%, medium/heavy-duty vehicles – 25%, aviation – 3%, and rail – 2% (Saundry, 2021b). Decomposition analysis, an environmental and energy analysis tool, has been useful in studying historical GHG emissions and energy use in various segments of the US transportation sector. This analysis uses the Kaya Identity variation for the transportation sector, which decomposes overall transportation CO2 emissions into four primary drivers: fuel carbon intensity, vehicle fuel consumption, population, and travel demand. (Scholl et al., 1996; Lakshmanan and Han, 1997; Mui et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2009; McCollum & Yang, 2009).

The valuable characteristics of petroleum-based transportation fuels, namely energy density, chemical conversion, and deployability, bring unique challenges in moving away from petroleum-based fuels (Gross, 2020). Since fossil fuels represent the primary energy source for most transportation segments, the sector is considered a difficult one to decarbonize (Meyer, 2020). The magnitude of complexity in decarbonizing road transportation also varies across its parts. Some transportation segments are maybe more complicated to decarbonize than others. For example, the expected fast growth of heavier forms of road transportation intensifies the challenge of displacing petroleum-based fuels in the sector. Per the International Energy Agency (IEA), the oil demand in heavy trucking will increase by 25% by 2040. In contrast, despite the growth of light-duty vehicles on the roads, IEA predicts the peak oil demand from these vehicles in the early 2020s. More efficiency in vehicles and transportation electrification reduce petroleum-based fuel consumption in the light-duty vehicle segment (Gross, 2020).

Electrification is considered the most attractive technology for a light-duty fleet (especially passenger cars) that carry lighter loads while traveling shorter distances. Papadis and Tsatsaronis (2020) advise that "electromobility can be applied to cars and trucks and is included as an option in most scenarios" (p. 7). Namely, the researchers believe that the electrification of transportation may serve as one of the best approaches for the transportation sector. However, the total decarbonization of the transportation sector through electrification may be problematic (IRENA, 2018). Saundry (2021c) also states that "the key variable for EVs is the level of emissions associated with generating the electricity used in the vehicle" (p.7). In other words, the electrification of transportation will only be successful if it is appropriately coordinated with the decarbonization of the power sector. Therefore, Gillispier and Krisher (2021) believe that, in the long-term, hydrogen may serve as an additional vital tool to reduce carbon emissions from the transportation sector, which represents "the single biggest US contributor to climate change" (para. 4). In other words, the hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector may complement the electrification of vehicles in the broader context of the US energy transition.

Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) and battery electric vehicles (BEVs) represent the two main options for the zero-emissions US road transportation sector. FCEVs are electric vehicles with refueling times and driving ranges similar to internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles (IRENA, 2008). Both types can be used for various transportation segments (light/medium/heavy-duty vehicles). BEVs store energy as electricity in batteries, whereas FCEVs store energy (15 kWh/kg) as hydrogen and then convert it to electricity through fuel cells (FCHEA, 2020). The fuel cell is "an electrochemical device that can be used to generate electricity or store energy in the form of hydrogen” (Andrews and Jelley, 2017, p. 405). The suitable materials and chemicals for the anode and cathode, electrolyte and catalyst represent the fundamental challenge in creating an efficient fuel cell (Saundry, 2021a). There are various fuel cells: polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM), solid oxide fuel, molten carbonate, phosphoric acid, alkaline fuel, and alkaline exchange membrane fuel cells. PEM fuel cells usually operate at about 80°C and respond rapidly to changing loads, making them appropriate for various transportation applications (DOE, 2020c).

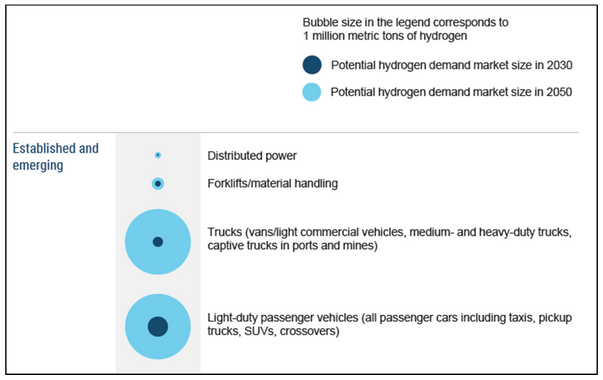

FCEVs might compete with BEVs in some on-road transportation segments. However, IRENA (2018) asserts that "for each [road transportation segment], there is a clear competitive advantage for either FCEVs or BEVs" (p. 32). Although the FCEV deployment has been focused on the passenger light-duty vehicle segment, the real opportunity for hydrogen deployment exists for heavier vehicles traveling long distances. Goldman Sachs (2022) asserts that "clean hydrogen could be a key competing technology [for heavy vehicles], given its high energy content per unit mass (lighter) and faster refueling time" (p. 89). IRENA (2008) states that FCEVs have potential in the heavy vehicles segment (trucks and buses) in the short-medium term. In addition, FCEV long-term potential exits in the medium/sizeable light-duty passenger cars with high utilization rates (taxis or last-minute delivery vehicles). FCHEA (2020) believes that by deploying FCEVs through 2050, the US road transportation sector will be one of the biggest beneficiaries of hydrogen fuel (Figure 3).

The following section discusses the challenges of hydrogen deployment in the US road transportation sector.

The lack of adequate hydrogen fuel supply for the road transportation sector, absence of hydrogen infrastructure, economic issues, decarbonization policies' drawbacks, and the necessity to improve safety codes/standards and fueling protocols for medium/heavy-duty vehicles are the main potential challenges for successful hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector.

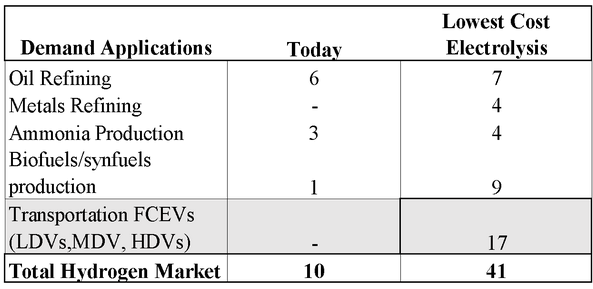

The lack of sufficient liquid hydrogen supply for FCEVs represents the first challenge for scaling FCEVs in the US road transportation sector. Neil (2022) notes that "people assume hydrogen is abundant. It isn't – not in a readily usable form" (para. 4). For example, the United States, annually, produces only about 10 MMT of hydrogen (DOE, 2020a). As a chemical feedstock, the primary demand for hydrogen comes from ammonia production and petroleum refining. Small amounts of hydrogen are used in a few industrial applications, namely methanol production (DOE, 2020c). US hydrogen production primarily comes from fossil fuels (99%), natural gas through SMR (95%), and partial oxidation of natural gas through coal gasification (4%). Electrolysis is used only in 1% of US hydrogen. In contrast to the United States, 70MMT of hydrogen is produced globally. Global hydrogen production comes from natural gas through SMR (76%), coal gasification (22%, mainly in China), and electrolysis (2%) (DOE, 2020a).

Table 2 shows the current and future hydrogen economic potential breakdowns in the Lowest-Cost Electrolysis scenario. As seen from the table, in the most ambitious scenario, by 2050, the US needs to increase the supply of transportation FCEVs from a currently negligible amount to 17 MMT. Therefore, the US faces the daunting task of quickly ramping up the hydrogen supply for transportation and other sectors to decarbonize its economy.

The absence of a reliable public and private hydrogen infrastructure for the road transportation sector is the second challenge in achieving widespread FCEV adoption across the United States. This infrastructure consists of hydrogen transportation, storage, and distribution (dispensing and fueling) (DOE, 2020c). Incidentally, “[hydrogen] transportation, distribution, and storage are the primary challenges of integrating hydrogen into the overall energy economy system” (DOE, 2020a, p.11). Neil (2022) agrees that even if low-carbon hydrogen were plentiful, it would be challenging to develop hydrogen transportation and delivery for the road transportation sector.

Hydrogen transportation and storage are challenging since hydrogen has a low-volumetric density at room temperature (nearly 30% of methane at 15°C, 1 bar) and quality to pervade metal-based materials. There are four primary methods for hydrogen transportation at scale: tube trailers, pipelines, liquid tankers, and chemical hydrogen carriers. Gaseous hydrogen can be transported by pipelines or tube trailers, whereas liquid hydrogen may be moved by liquid tankers or marine vessels. The current portfolio of hydrogen storage options consists of physical-based (compressed gas, cold/cryo-compressed, liquid, and geological) and material-based (metal hydrides, absorbents, and chemical hydrogen carriers). Currently, there are no material-based storage options ready for widespread commercialization. Energy densities in cryo-compressed and liquid hydrogen storage systems may benefit medium/heavy-duty vehicles' infrastructure rollout. However, the need for boil-off, venting, and insulation, which occur from extended dormancy, adds costs and challenges to the system's performance (DOE, 2020c).

Hydrogen distribution (dispensing and fueling) is the last vital part of hydrogen infrastructure for the road transportation sector. Sinha and Brothy (2021) proclaim that "the hydrogen refueling network is the main barrier to FCV adoption because consumers will only purchase an FCV if the stations exist to refuel it" (p.7). In other words, US FCEV drivers require ample hydrogen fueling station (regional and/or nationwide) coverage to reassure them that fueling will not be a problem. There are 48 public hydrogen fueling stations in the US, 47 in California, and 1 in Hawaii (Neil, 2022). Overall, the US will need to invest in significant research and development (R&D) efforts to increase the throughput of hydrogen dispensing systems and other related systems at the fueling stations. Moreover, R&D efforts are required to improve the reliability of materials used in the compressors and develop new designs for cryogenic transfer pumps, compressors, and dispensers to ensure they have sufficient throughout the medium/heavy-duty vehicle fleet (DOE, 2020c). Overall, the demands placed on hydrogen transportation, storage, and hydrogen delivery present challenges for the initial introduction and the nationwide scale-up of hydrogen infrastructure for the road transportation sector.

Economics is the third hurdle to successful hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector. The three-pronged economics issue is connected to the costs of hydrogen production, fueling infrastructure, and FCEVs. First, the current production cost of low-carbon hydrogen is a costly process. In the United States, gray hydrogen costs $2/kg, blue hydrogen costs between $5-$7/kg, and green hydrogen costs $10-$15/kg, depending on availability (SGH2 Energy, 2022). DOE Hydrogen Program describes that the US might produce hydrogen from polymer electrolyte membranes (PEM) at approximately $5-$7/kg. This calculation assumes grid electricity prices between 5-7 cents/kWh, existing technology, and low volume electrolyzer capital costs (CapEx) at $1,500/kW. Hellstern et al. (2021) stress that the significant hydrogen end-users would consider hydrogen economically viable if the fuel is made at $1/kg in the United States and $2/kg in the European Union. Second, the costs of building hydrogen infrastructure will be prohibitive. For example, Neil (2022) notes that the costs of presently available hydrogen fueling stations during the past decade are much higher than associated costs with traditional gas stations. Such costs usually include the costs of the natural gas reformer on-site to evade the necessity of high-capacity storage tanks and pipelines. Additional costs of hydrogen fueling stations are connected to the compliance costs associated with local, state, and federal safety regulations.

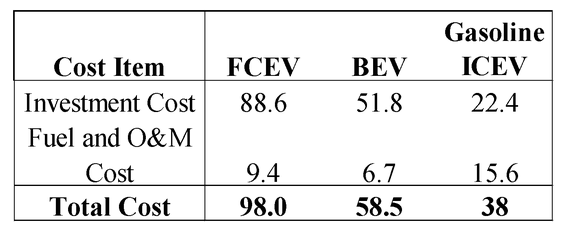

Lastly, the broad adoption of FCEVs also relies on the relatively inexpensive cost to consumers. Compared to ICEVs and even BEVs, the high cost of FCEVs may preclude such widespread rollout of FCEVs in the road transportation sector. For example, the researchers analyzed the cost components for different vehicle types in Austria and Germany in 2016 (Table 3). The results show that, at present, FCEVs and BEVs are more expensive to operate than conventional vehicles. However, BEVs are less costly than FCEVs in investment, fuel, and operations costs. The fuel cell cost accounts for nearly half of the investment cost for FCEVs (Moriarty & Honnery, 2019). The main contributor to the cost of a fuel cell is the catalyst, which is based on the platinum group metals that are highly dependent on imports. Other components also need additional R&D improvements to meet low-cost targets for fuel cells, such as electrolytes or membranes, bipolar plates, etc. The cost reductions for fuel cells need to happen while maintaining efficiency and improving the durability of components (DOE, 2020c). To sum up, high costs of production, fueling infrastructure, and FCEVs may hinder the hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector.

Drawbacks from decarbonization policies might become the fourth roadblock to successful hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector. The United States, along with various nations worldwide, has implemented internal combustion engine phase-out policies. Biden's administration aims to "50 percent of all new passenger cars and light trucks sold in 2030 be zero-emissions vehicles, including battery-electric, plug-in hybrid electric, or fuel cell electric vehicles" (Saundry, 2021c). Andrews and Jelley (2017) affirm that policy changes may encourage the shift in the transportation modes and assist decarbonization efforts.

However, due to the urgency of the fight against climate change and ambitious decarbonization targets in some states, accurate technology winners might not be discovered quickly enough to justify large-scale hydrogen infrastructure buildout. Gross (2020) warns about the potential policy drawbacks in very ambitious jurisdictions: "Policy has the potential to drive vehicle uptake and infrastructure development, but at the risk of not allowing the technology competition to play out fully" (p. 11). In other words, the policies that encourage the shift to a low-carbon vehicle fleet might stifle the competition to establish an accurate technology winner for road transportation segments. Namely, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) passed a new rule in June 2020, which requires broad adoption of zero-emissions trucks, beginning in 2024, with all heavy-duty vehicle sales being zero-emissions by 2045. The CARB does not stipulate a specific technology in the ruling. Electric trucks are currently ahead of other technologies in research and development efforts.

Furthermore, through the West Coast Clean Transit Corridor Initiative, the US West Coast utilities are ready to offer the charging infrastructure for BEVs. Even though the CARB ruling is technology-neutral, such policy will significantly benefit California's electric medium/heavy-duty trucks. The District of Columbia and fifteen states in the US Northeast also signed a memorandum of understanding to follow California's initiative. Thus, policies may accelerate decarbonization in the road transportation sector by encouraging the electrification of medium/heavy-duty vehicles. However, such policies might leave the deployment of hydrogen infrastructure and FCEVs significantly behind. The policy drawbacks might also be amplified by the miscoordination of federal, state, and local efforts during the hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector.

The implementation of safety standards is the fifth potential challenge in the US hydrogen deployment in its most carbon-intense sector, road transportation. Hydrogen has been safely used in different industrial sectors, such as refining and chemicals, for more than seventy years. Its chemical properties give hydrogen a better standing than fossil fuels inflammability, risk of secondary fires, and quick dissipation. Nevertheless, hydrogen is a flammable, odorless, invisible gas requiring stringent safety measures. The US needs to implement such actions in hydrogen production, use, and handling, namely leak detection systems, storage tanks, and safety valves (FCHEA, 2020). Thus, hydrogen standards need to be constantly revised, in concert with the R&D efforts in the US and abroad, as hydrogen continues to be deployed in the road transportation sector.

The rapid development of fueling standards for medium/heavy-duty vehicles might be the last challenge of hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector. Once hydrogen is transported to the hydrogen fueling stations, it may need to undergo the additional process for conditioning, such as pressuring, cooling, and purification. Hydrogen is usually stored on-site in bulk. Hydrogen fueling stations for all vehicles (light, medium, heavy-duty) usually have high-pressure compressors, dispensers, and storage vessels – all these systems are required to permit hydrogen fueling per specific standard protocols. The fueling standards for light-duty vehicles are currently developed, with the technology commercially deployed in the current FCEV hydrogen fueling stations across the United States. For example, the fueling pressure for light-duty vehicles is typically 10,000 psi or 70 MPa (700 bar). However, the fueling standards for medium/heavy-duty vehicle fleets are yet to be established, and such measures need to inform the equipment requirements for the hydrogen high-throughput stations (DOE, 2020c). The US needs to coordinate its R&D efforts with similar efforts globally (FCHEA, 2022). Thus, the rapid development of reliable fueling standards for medium/heavy-duty vehicles is essential for successful hydrogen deployment in the US road transportation sector.

To summarize, the lack of hydrogen supply and infrastructure, economic issues, the drawbacks of decarbonization policies, the urgency to improve safety codes/standards, and fueling protocols for medium/heavy-duty vehicles are primary potential challenges for successful hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector. The following section discusses the opportunities for hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector.

The main prospects for hydrogen deployment in the road transportation sector are the availability of domestic natural resources, technologies, additional resources (storage and liquefication), supportive hydrogen-related policies, and the FCEV’s advantages over BEVs and ICEs.

The United States has various primary energy resources to produce low-cost, low-carbon, secure, sustainable, and large-scale hydrogen, including fossil, biomass, and waste-stream resources (DOE, 2020c). The US possesses sufficient low-carbon and renewable electricity sources for green hydrogen, such as solar, wind, nuclear, and hydropower (FCHEA, 2020). Currently, the country consumes and produces about 10 MMT/year, about one percent of US energy consumption (DOE, 2020c).

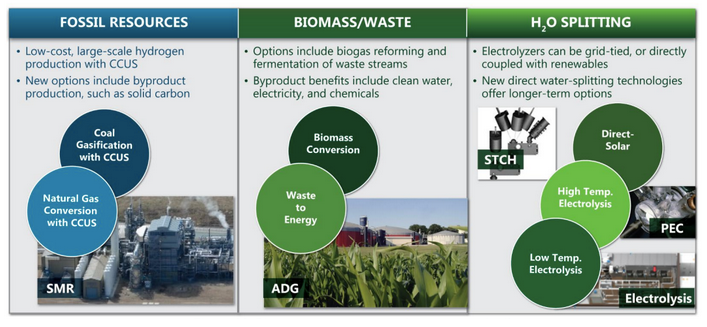

At the same time, the US is rapidly exploring and developing hydrogen production technologies, which can utilize these natural resources through natural gas and coal gasification with CCUS, biomass conversion, waste-to-energy technologies, and various water-splitting technologies (Figure 4). Such a wide array of natural resources and technologies spread across the country can help increase its hydrogen supply from "a few hundred to hundreds of thousands of kilograms per day” (DOE, 2020c, p. 15).

Fossil Fuels. Presently, natural gas and coal are the two primary fossil resources utilized for global hydrogen production (DOE, 2020c). Natural gas, produced in rock formations, contains the remains of tiny creatures fossilized under immense heat and pressure throughout millions of years (Andrews & Jelley, 2017). Coal is a "carbon-rich solid, which originated in vast swamps containing large trees and leafy plants" (Andrews & Jelley, 2017, p. 74). Based on the differences in carbon content, coal can be divided into lignite, bituminous, sub-bituminous, and anthracite (Saundry, 2021d). The US remains the largest natural gas consumer despite its decline in the share of global gas consumption (Saundry, 2021e). Due to the relatively recent fracking boom of "unconventional resources," the US currently is the largest global producer (with a 24% share) of natural gas (Saundry, 2021e). Approximately 95% of US hydrogen is produced through SMR methods based on prevailing natural gas infrastructure. FCHEA (2020) claims that the US has ample affordable natural gas and carbon storage capacity to produce blue hydrogen (natural gas with CCUS) on a massive scale. In the near term, CCUS can be utilized with auto thermal reforming (ATR - conversion of steam, natural gas, and oxygen to syngas), partial oxidation of natural gas, and gasification of coal or biomass/coal/plastic waste blends.

Other developing technologies include direct methane pyrolysis into hydrogen and solid carbon. There are currently promising hydrogen production systems that can produce hydrogen for less than $2/kg. One of the successful examples of an SMR/CCUS project is the integrated hydrogen production facility at the Valero Refinery, the Port Arthur (SMR/CCUS project) (Preston, 2018). In the long-term, the reductions in capital and operating costs and further R&D advances in technologies can lead to low-carbon production at less than $1/kg. In addition, steam cracking (cracking natural gas liquids) can also produce affordable hydrogen as a by-product of this process. The current hydrogen production capacity is 2 MMT/year, which will increase to 3.5 MMT/year from the deployment of additional steam cracking plants soon. The DOE estimates that, if properly implemented, this process can provide 35% of current hydrogen demand and provide opportunities to co-locate end-use applications in various US regions (DOE, 2020c).

Biomass/Waste-Stream. Primary biomass sources (poplar, willow, switchgrass) and biogas, derived from anaerobic digestion of organic residues from agricultural waste, municipal solid waste, and landfill sources, can be used for US hydrogen production. The feedstock potential for such resources is more than a billion dry tons annually (DOE, 2020c). Biomass is an attractive, sustainable low-carbon energy source due to the basic cycle for bioenergy, which recycles carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and releases the same carbon dioxide during burning (Andrews and Jelley, 2017). Biomass can be gasified on its own or during the gasification processes for waste plastics and coal. The processing of primary biomass into bio-derived liquids for consequent reforming into hydrogen, together with CCUS, may produce carbon-negative hydrogen.

Furthermore, biogas can be reformed through an SMR-like process into hydrogen after additional clean-up procedures. Through microbial-assisted electrolysis, fermentation, or non-thermal/thermal plasma-based processes, producers can use waste-stream feedstocks for hydrogen production. Based on the availability and costs of biomass/waste-stream resources, producers can commercially deploy some types of technologies (SMR/gasification of biomass and waste streams) in the short term. In the long-term, R&D initiatives in conversion efficiency and the decrease in costs of transporting/pre-treating feedstocks will make this type of hydrogen production economically competitive (DOE, 2020c).

Water-Splitting Technologies for Hydrogen Production. Hydrogen producers can use various water-splitting technologies, which utilize electric, photonic, or thermal energy from US low-carbon and renewable energy resources (DOE, 2020c). Electrolysis is considered a "promising option for carbon-free hydrogen production from renewable and nuclear resources" (DOE, 2022a). Andrews and Jelley (2017) explain that electrolysis serves as vital technology in the energy storage and the synthesis of low-carbon fuels through hydrogen production. The US has abundant renewable and low-carbon electricity resources, crucial for hydrogen production. For example, solar photovoltaics and wind power enable hydrogen production on both distributed and centralized basis throughout almost all US regions. Concentrated solar power (in the south-western region) and solid biomass (in the central and eastern regions) are other potential renewable energy sources that the US may use for hydrogen production. Lastly, present nuclear plants can be co-located next to the large-scale hydrogen production facilities (DOE, 2020c).

Electrolyzers can be coupled with the US electric grid or be integrated with distributed generation assets for hydrogen production for various applications. An electrolyzer is defined as a “system that uses electricity to break water into hydrogen and oxygen” (Cummings, 2020, para. 1). IRENA predicts in its World Energy Transitions Outlook 2022that the cost of hydrogen electrolyzers will fall at similar rates to onshore wind and solar PV's decrease in the past decade (Collins, 2022). Low-temperature electrolyzers (membrane-based and liquid-alkaline) provide short-term commercial profitability, with units ready for industrial-scale production. The hydrogen cost for low-temperature electrolysis is connected to the US electricity cost. Currently, for electricity priced between $0.05-$0.07/kWh, hydrogen’s cost ranges between $5-$6/kg (DOE, 2020b). Hydrogen becomes cost-competitive, at less than $2/kg, if the electricity cost lowers to $0.02 - $0.03/kWh (due to the increase in solar/wind generation) along with R&D advancements in the durability and efficiency of electrolyzers (DOE, 2020c).

Additional Resources (Hydrogen Storage and Liquefaction). The US possesses more than 1,600 miles of hydrogen pipelines and three caverns, which can be used to store hydrogen on a massive scale. In addition, there are eight hydrogen liquefaction plants (cumulative capacity of 200 metric tonnes/day), with three more additional plants to be built in the near term (DOE, 2020c). These other resources provide tangible opportunities for hydrogen storage and transportation of liquified hydrogen to the end-users, especially in the road transportation sector.

Although the US has not yet announced an official national hydrogen strategy, the country has always supported hydrogen technology. In 1969, the US Apollo 11 mission, which put the first man on the moon, utilized a hydrogen fuel cell system for electricity/ water needs and liquid hydrogen as rocket fuel. Since this historic mission, the US has retained its leadership position in developing and commercializing hydrogen and fuel cell technology. Over the last decade, the US DOE provided funding for fuel cells and hydrogen ($100-$280 million/year) and $150 million/year since 2017 (FCHEA, 2020). More than ten years ago, the DOE's early investment in the forklift and material handling industry represented the US early market success for using hydrogen in transportation. As of 2020, more than 35,000 systems are commercialized by the US private sector without additional DOE funding. Hydrogen is also used in over 8800 commercial and passenger vehicles, with a growing hydrogen fueling infrastructure (DOE, 2020c).

Other developed countries have provided more significant financial support for developing their hydrogen economies. For instance, China declared $17 billion in funding for hydrogen transportation needs through 2023. In 2019, Japan announced hydrogen funding of approximately $560 million. Germany offers $110 million/year towards R&D efforts for hydrogen technologies for various industrial-scale end-uses. Therefore, FCHEA proclaims, "Directing capital to hydrogen is key to enabling its growth in the US" (FCHEA, 2020, p.6). In other words, large-scale government funding is crucial to lay down the foundation for all sectors of the US hydrogen economy, mainly in the road transportation sector.

Recently, the US has undertaken serious steps towards creating the solid groundwork for nationwide hydrogen solutions. For example, in 2020, the US DOE published Hydrogen Strategy and Hydrogen Program Plan, which describes the strategic framework for nationwide hydrogen deployment, H2@Scale. "H2@Scale is a DOE initiative that provides an overarching vision for how hydrogen can enable energy pathways across applications and sectors in an increasingly interconnected energy system" (DOE, 2020c, p. 8). Furthermore, launched on June 7th, 2021, the DOE Hydrogen Shot initiative seeks to reduce clean hydrogen's cost by 80% to $1/kg by 2031 (DOE, 2022b). In February 2022, the US "[entered] the hydrogen policy wave" by announcing $9.5 billion in clean hydrogen funding as a part of the US Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act (Goldman Sachs, 2022, p. 17). Here are the excerpts from Sections 40313, 40314, and 40315 of this Infrastructure Bill, which are relevant to the road transportation sector (Goldman Sachs, 2022):

Furthermore, in March 2022, US Senators Chris Coons (D-Delaware) and John Cornyn (R-Texas) introduced the Hydrogen for Trucks Act to assist with deploying heavy-duty FCEVs and hydrogen fueling stations. This act will 1) provide incentives for FCEV adoption by covering the cost difference between FCEVs and ICEs; 2) encourage parallel deployment of fueling stations and FCEVs, and 3) offer data and benchmarks for various kinds of fleet operations, which is supposed to accelerate deployment and incentivize private investment (Coons, 2022). To sum up, the trajectory of US pro-hydrogen policy and, mainly, the current political environment provides a vital boost for hydrogen deployment in the US road transportation sector.

According to FCHEA (2020), FCEVs have many advantages compared to BEVs and ICEs. Such benefits are based on 1) range/weight/powertrain volume, 2) fueling time, 3) diversification or reduction of raw material dependencies, and 4) performance consistency at various temperatures. Based on such prospects, FCEVs can be instrumental in various US transportation segments, complementing electrification, biofuels, and other powertrain strategies (FCHEA, 2020):

In essence, the hydrogen deployment in the US road transportation sector might benefit from domestic natural resources, technologies, additional resources (storage and liquefication), supportive domestic policies, and the FCEV's advantages over BEVs and ICEs. The following section discusses the hydrogen deployment strategy in the road transportation sector through 2050.

Read Part 2 of this article and find a full list of references here.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Hydrogen · Energy

illuminem briefings

Hydrogen · Green Hydrogen

illuminem briefings

Sustainable Finance · Biomass

CGTN

Hydrogen · Energy

Eurasia Review

Hydrogen · Energy

H2-View

Hydrogen · Energy