How to kick-start the North-West European clean hydrogen market

· 10 min read

There is a growing global consensus that clean hydrogen is an indispensable vector in achieving net-zero emissions in 2050, an objective now set by close to all G20 countries and beyond. International organisations like IEA, IRENA and the EU project an increasing role for net-zero electricity in the next decades, but further electrification (now at roughly 20%) won’t cover much more than 60% of the total energy mix. This implies that ‘greening of the molecules’ (today mainly oil and gas) becomes very urgent. That’s where clean hydrogen comes in to help decarbonize industry (refineries, chemicals, steel etc.), long-range/heavy-duty transport (trucks, ships, planes, buses, trains) and mid to long-time energy storage (weeks/months). In those applications, there are very few practical and cost-effective alternatives.

In short, clean hydrogen’s role in the energy transition is mainly complementary to clean electricity. The best sign of the growing global consensus on clean hydrogen is the fact that the leaders at COP26 included clean hydrogen as one of the key technologies in the Glasgow Breakthrough Agenda, thus pushing it centre stage at COP27 and beyond.

Countries around the world have embarked on formulating hydrogen strategies or roadmaps in the last few years. Japan, Korea and France already in 2017/2018. Australia, The Netherlands, Germany and the EU in 2020. By now over 30 countries have hydrogen strategies or roadmaps and this number is still growing, not even counting regions and cities. More recently, a number of countries with a significant production potential in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America have joined the game: Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman, Morocco, Egypt, Namibia, Mauritania, India, Chile, Uruguay, Brazil e.g. These countries see clean hydrogen not only as important for their own domestic energy transition, but also as a potential new export sector providing sustainable jobs and growth. Concrete import-export projects between continents are already under development. Australia and Brunei have delivered their first shipments of hydrogen to Japan in pilot projects. The Inflation Reduction Act in the US includes powerful fiscal incentives to boost investment in clean hydrogen, possibly even for exports.

Based on the country strategies and trade project plans, one can already see a new global commodity market emerging with net-importing countries (Japan, Korea, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium) and net-exporting countries (Australia, MENA countries, Chile, possibly Namibia, South Africa, the US and Canada). It will take decades to grow and mature, of course, but according to some projections the volume of the global clean hydrogen trade by 2050 may be comparable to the current gas trade. India and China are also working on hydrogen strategies, with India also positioning itself as a future net-exporter. According to a report from IRENA, this may also have important geopolitical implications.

The clean hydrogen strategy of the EC launched in 2020 is very ambitious. The EC strategy has a target of 40 GW electrolyser capacity in Europe by 2030 (mainly using solar and offshore wind), in addition Member States aim to scaling-up low-carbon hydrogen production from gas with CCS and nuclear. After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the EC launched RepowerEU which doubled the EU’s hydrogen targets for 2030, both for ramping up European hydrogen production & consumption, as well as imports. REPowerEU targets a production of 10 million tons of renewable hydrogen by 2030. Using clean hydrogen for significant decarbonisation of Europe’s industry, heavy-duty transport and seasonal energy storage will require such high volumes in 2030.

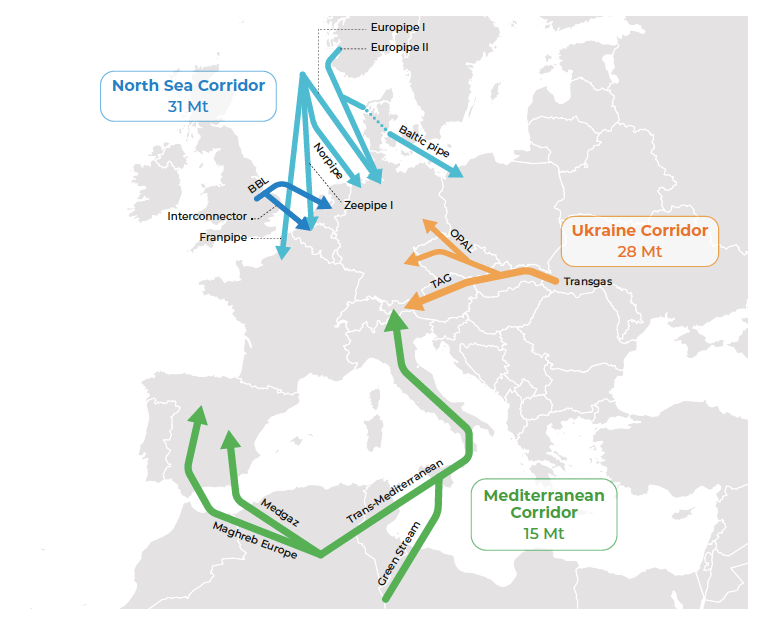

Beyond that, the EU matches its own production targets with aims to import 10 million tons of hydrogen and derivatives annually by 2030. For this, the EC is particularly focused on potential imports from Northern Europe, North Africa and Ukraine along three corridors (see graph).

The EC strategy has been welcomed by the European industry and broadly supported by member states. European energy infrastructure companies have developed a plan to create a European Hydrogen Backbone Infrastructure, largely based on the repurposing of gas pipelines, thus enabling clean hydrogen transport across Europe, including connections to North Africa (Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria). Having the infrastructure in place is a necessary, but not yet sufficient precondition to the kick-off and ramp-up of hydrogen. Repurposing enables efficient circular use of the existing infrastructure and makes use of an existing public good. The necessary integrated network planning for electricity and hydrogen grid is not only conducive to energy security but can also alleviate the burden on budgets.

Currently, the EC is working on the implementation through subsidy programs and putting in place the regulatory framework. Germany and the Netherlands are both also considering doubling their domestic renewable hydrogen targets. Clean hydrogen is now seen not only as indispensable for the energy transition, but also for reducing the dependence on fossil fuel imports from Russia. Energy security has become a second important driver for clean hydrogen, increasing the urgency. The need for accelerating implementation is commonly acknowledged. However, this is proving to be a huge challenge to act upon. The current obstacles include a tendency to overregulate, a business-as-usual attitude to policy-making, a lack of prioritising large projects (like NortH2) that can deliver most of the required scale-up by 2030 and a lack of strategic alignment between key member states. Whereas Germany and the Netherlands consider clean hydrogen imports as absolutely critical and already joined hands in the import program H2Global, France eyeballs a European hydrogen future based on sovereignty and production within Europe. The same dichotomy applies to the need for constructing a European Hydrogen Backbone. The latest German-French summit statement of 21 January 2023 about extension of the announced Barcelona-Marseille hydrogen pipeline to Germany may indicate a possible ‘rapprochement’ between the German and French strategy, though. There is in our view still a very serious risk that the EU will not be able to achieve its ambitious hydrogen objectives due to slow implementation, fragmentation and lack of strategic alignment between key member states. The consequence of a failure of the hydrogen strategy for Europe may well be severe deindustrialisation if European manufacturing industry is not able to decarbonise before 2050. The implication will also be that the EU will be severely limited in playing its role in the geopolitical hydrogen game in Africa and the Middle East, thus leaving the field for other major players. The most recent reports of the IEA, both the Global Hydrogen Review 2022 and the Northwest European Hydrogen Monitor 2022, show clearly that the EU is falling behind in implementation of the clean hydrogen objectives with less than 5% of planned projects in the phase of Final Investment Decision (FID) or under construction. And this while the majority of announced and planned clean hydrogen projects are actually in Europe, as every Hydrogen Council report is consistently showing. How to advance against this background? We propose three concrete steps that can be implemented already in 2023.

In the current situation, the EU member states that are already well aligned, Germany and the Netherlands, could consider a number of bold steps to accelerate the scale-up of the North-West European clean hydrogen market required to achieve the ambitious German and Dutch targets:

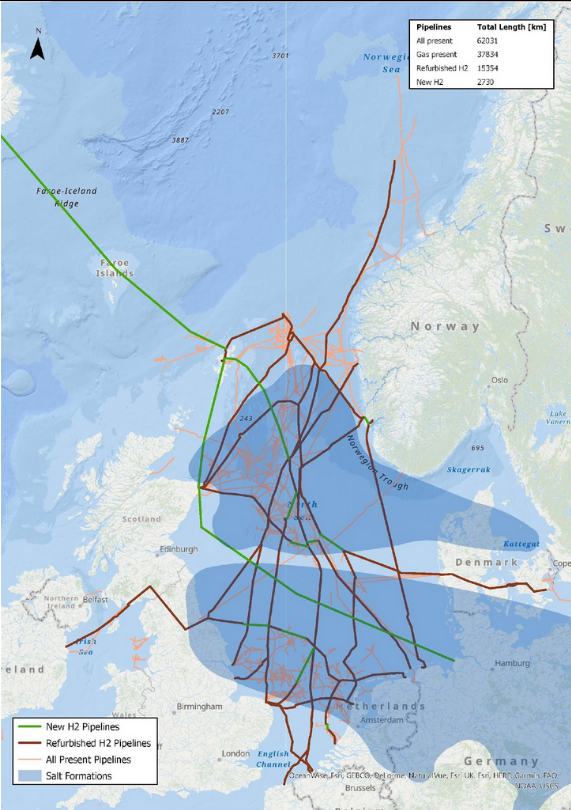

The second step could be a new initiative in the existing framework of North Sea countries cooperation, aiming at building an integrated cross-border offshore hydrogen infrastructure, where planned offshore renewable hydrogen production on artificial islands is connected to an extensive pipeline infrastructure that may include Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, the UK with Scotland as a potential renewable hydrogen exporter, Denmark, Norway and Iceland. Countries could establish a special taskforce to produce a roadmap for the next 10 years to realize this. The graph below is an inspiring illustration of what this may look like.

To be very clear, Dutch-German cooperation as described above is only the nucleus and starting point. The third and next steps that have to follow are expanding the collaboration regionally with Belgium, Denmark etc. and working together with other transnational regions in Europe across the Baltic Sea and with Southern and Southern East Europe. Such a sequential regional collaboration will be conducive to build a European hydrogen infrastructure, e.g. with Spain, Italy and Portugal. This dialogue can be focused on planning and executing concrete joint projects that establish clean hydrogen trade corridors by ship and pipelines.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

[1] Clean hydrogen is here defined as near-zero carbon hydrogen, produced by renewable or nuclear electricity or gas with very high rates of Carbon Capture & Storage (95% or higher).

[2] See IEA, An updated roadmap to Net Zero Emissions by 2050, 2022.

[3] Hydrogen (europa.eu)

[4] See e.g. Marcel Fratscher, ‘Droht Deutschland jetzt die Deindustrialisierung?’ , Handelsblatt, 10/01/2023.

[5] See e.g. Marcel Fratscher, ‘Droht Deutschland jetzt die Deindustrialisierung?’ , Handelsblatt, 10/01/2023.

illuminem briefings

Hydrogen · Green Hydrogen

illuminem briefings

Green Hydrogen · Hydrogen

illuminem briefings

Green Hydrogen · Sustainable Business

Energies Media

Green Hydrogen · Hydrogen

Hydrogen Insight

Green Hydrogen · Hydrogen

Hydrogen Insight

Hydropower · Green Hydrogen