· 10 min read

This article is the third in a series of six, based on a research by Dr. Venera N. Anderson, “Comparative Analysis of Green and Pink Hydrogen Production in Japan Based on a Partial Circular Economy Approach”. You can read part one and two here.

Japan is currently facing urgent energy and environmental challenges, demanding bold and sustainable solutions. As the world’s fifth-largest carbon emitter, the country must rapidly transition to cleaner energy sources to meet its 2050 carbon neutrality goal. Recognizing hydrogen’s potential, Japan has committed to major investments, including the $400 million Japan Hydrogen Fund and extensive government-backed incentives. However, while hydrogen is often seen as a “clean” energy source, its production and supply chains still carry emissions and environmental trade-offs. Identifying the most reasonable, practical, and economic source of clean hydrogen (green or pink) beyond 2040 is therefore critical. This research examines Japan’s energy and environmental situation, exploring how hydrogen, produced using a partial circular economy approach, could become the future cornerstone of Japan’s energy strategy.

Methodology

The thesis's focus on applying a partial CE approach in future Japanese green or pink H2 hubs was initially inspired by the Japanese “mottainai” movement (reduce, reuse, recycle, and respect) (Government of Japan, 2024). The methodology for answering the research question was based on three theoretical frameworks. The first theoretical framework relied on the technical cycle of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2024)’s CE system diagram (Figure 1). This diagram illustrated that the larger outer loops encircled the smaller inner loops. The inner loops were considered more valuable since most of the value was captured while retaining more of the embedded value of the product by keeping it whole. These loops also represented cost savings to businesses or customers as they used products and materials already in circulation. The study viewed a future Japanese green or pink H2 hub as a hypothetical” product user” in the center of the technical cycle of the Ellen Macarthur Foundation’s (2024) CE system diagram. Also, throughout the comparative analysis, the study identified the existing or potential elements of these loops or stages in the technical cycle in the development of Japan’s green and pink H2 hubs, namely 1) share, 2) maintain/prolong, 3) reuse/redistribute, 4) refurbish/remanufacture, and 5) recycle.

The study also utilized the author's two qualitative concepts developed in previous research papers during the Johns Hopkins Energy and Policy Master’s in Science program. These concepts were the quasi-revolutionary transition for developing US coastal green H2 hubs (Anderson, 2022) and nexus-integrated policies for Japan (Anderson, 2023). First, the quasi-revolutionary transition was the transition governance model for developing US coastal green H2 hubs (Anderson, 2022). The transition governance model, initially formulated by the Dutch Research Institute of Transitions (DRIFT), was "radical in the long-term, diplomatic in the short-term" (Loorbach, 2022, p. 2). Anderson's (2022) concept was based on the DRIFT's model, transformed by the inclusion of van den Bergh's evolutionary-technical perspective on sustainable development (Zachary, 2014), Sheer's "Energy Imperative" (2012), and the author's additional recommendations. The modified DRIFT's pillars informed the vision and recommendations for developing US coastal green H2 hubs: 1) systemic (engage with emerging dynamics across societal levels), 2) back-casting (focus on the desired transition as a starting point), 3) selective (work with transformative agencies already engaging with the transition), 4) adaptive (experiment with multiple goals and transition pathways), and 5) learning-by-doing and doing-by-learning.

Second, nexus-integrated policies for Japan were cross-sectoral policies for improving Japanese environmental and energy situations (Anderson, 2023). This concept was based upon the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI)-framework (Hoff, 2011) and the author's proposed sectoral actions for energy and environmental resilience and reliability and environmental security. The policies were anchored on the SEI's framework pillars: 1) economy (creating more with less), 2) environment (investing in sustaining ecosystem services), and 3) society (acceleration of integration and better integration of the poorest). The framework accounted for population growth, climate change, and urbanization as pressures on ecosystems and limited resources. Finance, innovation, and governance were vital for implementing these nexus-integrated policies (Hoff, 2011). Moreover, the nexus-integrated policies proposed additional policy recommendations: 1) appreciation that the most feasible options to reinforce energy situations require longer timeframes and might not be similar actions to solve environmental challenges, 2) formulating a multi-dimensional CE, 3) analyzing the supply chains and lifecycle emissions of cleaner energy alternatives and choosing the best options for the energy transition, and 4) assuring the just and orderly energy transition, while accounting for various net externalities and tradeoffs (Anderson, 2023; Sullivan, 2022).

Data background

The study conducted an integrative literature review using various qualitative and quantitative resources to collect data and conduct analysis to answer the research questions. Keywords like “hydrogen,” “clean hydrogen,” “low-emissions hydrogen,” “hydrogen strategy,” “green hydrogen,” “pink hydrogen,” “electrolysis,” “Japan,” “circular economy,” “wastewater,” “nuclear energy,” “solar energy,” “wind energy,” and “renewables” were used for all database searches. The thesis’s methodology governed the data selection and analysis. The foundation for the clean H2-specific data for the Introduction, Methods, Analysis, and Discussion was gathered from published primary sources (government reports, research reports, and articles), secondary sources (review articles, textbooks, and websites with reliable qualitative and quantitative information), and case studies of other countries facing similar problems like Japan.

Industry resources were systematically chosen with the lens of utilizing the thesis’s methodology by selectively using resources from organizations that are considered trustworthy, utilize recent industry data (published after 2020), and are commonly referred to in the clean H2 space, such as the Hydrogen Council, the Hydrogen Insight, Clean Hydrogen Partnership, Lazard 2024 LCOE+ Report, and the Japan NRG. Additionally, recent newspaper articles provided the context for the Japanese socio-political context. Lastly, three energy Japan-based professionals, Mr. Shoichi Itoh (Senior Fellow, Energy Security Unit, the Institute of Energy Economics, Japan); Mr. Yuriy Humber (K.K. Yuri Group and founder of Japan NRG); and Mr. Hidetaka Endo (GX/SX Business Expert of GX business development in the Technology Development Department at Mitsubishi Kakoki, Ltd) informally provided answers about the current state of green and pink H2 development, through additional research (Itoh), the weekly Japan NRG reports and a few brief consultations (Humber), and a recollection of a professional experience of working on a green H2 project in Japan (Endo).

Analysis

The thesis research proposal initially focused on comparing the nesting dolls of various types of clean H2 production (anti-fragile multi-dimensional green and pink H2 production systems in Japan based on a complete CE approach). The thesis initial draft was called “Operation Nesting Doll” to reflect the thesis’s mentor (Dr. Paul J. Sullivan)’s assertion that “a circular economy is a system within systems nested in systems and then linked to other systems and a recurring circle of resources and products. The circles need to be closed” (Sullivan, 2022). Interestingly, the nesting doll craft originated in Asia before moving to Russia. The origin of a matryoshka is Japanese since Sava Mamontov brought a Japanese fukurumafukurama doll and made the first matryoshka doll in 1892 (The University of Kansas, 2024). The research process revealed the lack of specific public data about individual complete circular systems nested in Japan's green or pink H2 domestic production. Therefore, the author decided to perform a qualitative comparative analysis of green and pink H2 production in future Japanese clean H2 hubs based on a partial CE approach, using public quantitative and qualitative resources from Japan and other countries.

Hydrogen hubs in Japan

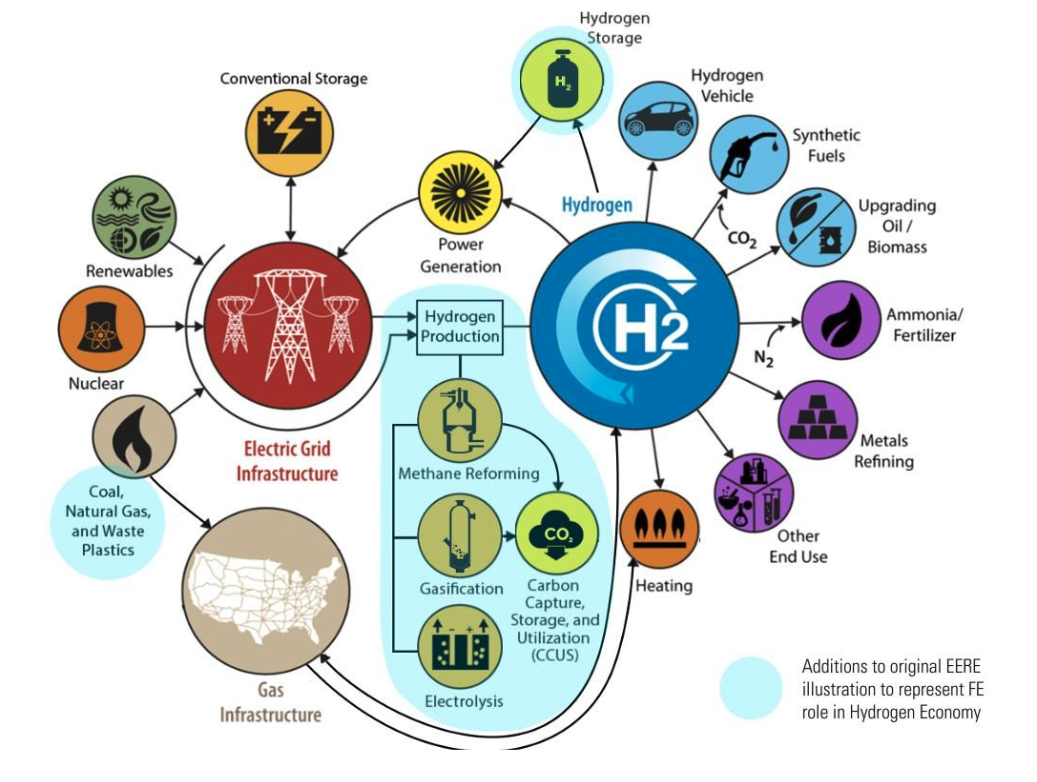

Clean H2 infrastructure comprised production, storage, transmission, and distribution (DOE, 2020), as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10

Clean Hydrogen Infrastructure Schematic

Note: Integration of Fossil Energy into the Hydrogen Economy (Figure E1). From Hydrogen Strategy: Enabling a low-carbon economy by DOE (2020).

Clean H2 hubs were "networks of clean [H2] producers, consumers, and connective infrastructure that [would] help accelerate the large-scale production and use of clean [H2]" (DOE, 2024, p. 1). The current studies and projects in Japan focused not on a large domestic clean H2 production but on building supply chains (Watanabe, 2024a). For instance, Japan designated ten candidate sites to serve as clean H2 hubs, possibly three near big cities, five in the regions, and two not yet decided. The four most well-known hubs in various prefectures were only supply chain projects: 1) Ibaraki (clean H2 and ammonia), 2) Aichi (ammonia), 3) Kansai (clean H2), and 4) Hokkaido (ammonia). All blue H2 in Japan was expected to be imported (Japan NRG, 2024b). Moreover, green H2 has been produced at a small scale since 2020 at 1) the FH2R plant in Fukushima prefecture, 2) Yamanashi Hydrogen Co in Yamanashi, and 3) the Obayashi geothermal plant in Oita. Due to the high costs, these projects were labeled dream projects with little market potential.

Despite such dismal progress, in 2025, a few newly planned green H2 projects might come online, such as Hokkaido, Yamanashi, and Fukushima prefectures, adding "craft supply" for local economies. This time, municipal governments are energizing the green H2 industry since they want to monetize excess renewables (wind/solar) electricity, which is left redundant due to a lack of transmission cable bandwidth. In Japan, renewable operators are frequently asked to curb output from May to September due to the excess generation of solar power (Watanabe, 2024b, p. 19). Curtailment affects all the country's power systems except Tokyo. The situation is more problematic in Kyushu, where the curtailment rate of wind and solar power was projected to reach approximately 7% in FY2023. Reducing curtailment in Japan can be achieved by prioritizing two main regulatory solutions: negative prices and economic dispatch (Zissler, 2024).

Some experimental pink or other nuclear H2 projects do exist in Japan since the previous administration (Kishida) focused on pink H2 production via high-temperature engineering test reactor (HTTR) (IAEA, 2024a; Engbarth, 2023). For example, Kansai Electric Power conducted a pink H2 demonstration project from October 2023 to March 2024 (KEPCO, 2024). The safety demonstration test confirmed that the reactor could cool itself in case of an accident, sparking hope for pink H2 production (Japan NRG, 2024b). As green and pink H2 domestic productions mature in Japan, it would be crucial to focus on the CE approach in their developments (CHP, 2024a). Therefore, the thesis's methodology was utilized in setting up the multi-criteria comparative analysis of green and pink H2 production in Japan based on a partial CE approach (Table 2 and Table 3, Appendix).

Comparative analysis

The thesis focused on the partial CE approach regarding exploring the best reasonable, practical, and economic future (2040-beyond) source of clean hydrogen (H2) (green or pink) for Japan. Due to sparse and, in many cases, unavailable public data on Japan for green and pink H2 production, the analysis had to take a somewhat simplified approach in the choice of its criteria. The primary criteria for the comparative analysis of Japanese green and pink H2 production based on a partial CE approach were grouped into four broad areas: 1) economic, 2) impact on the environment, 3) safety, and 4) workforce availability. The economic criteria were split into three categories: 1) selected OPEX (operating expenses), including costs of electricity/heat with associated capacity factors, and that of water consumption; 2) CAPEX (capital expenditure), including CAPEX for hubs/wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) and the cost of electrolyzers; and 3) subsidies. Other criteria included 1) impact on the environment, 2) safety, and 3) workforce availability (Tables 2 and 3, Appendix). The list of the criteria and its ingredients was not exhaustive, so it should be expanded in the future to incorporate additional refinement in the analysis. For instance, it might include all specific OPEX related to running a Japanese green or pink H2 hub, grid fees, taxes, and oxygen sales (CHP, 2024b). Finally, the analysis might incorporate additional considerations concerning technical issues and policy/regulatory support, which could affect the economic viability and sustainability of Japanese green and pink H2 production.

Japan is a unique island nation with a remarkable track record of confronting and transcending adversity. Today, the country faces significant energy and environmental challenges, yet it also possesses the innovation, resilience, and ambition to rise to the occasion. By building a circular economy around hydrogen, Japan can ensure a sustainable and resilient energy future. Pink hydrogen, produced based on a partial circular economy approach, offers the most reasonable, practical, and economic clean hydrogen solution for Japan beyond 2040. While the clean hydrogen sector is still navigating its path, the future lies in focusing capital, talent, and time on practical, sustainable solutions that match Japan’s unique energy and environmental context. Japan’s hydrogen economy will thrive if it emphasizes precision over hype.

For further details, you can find the list of references and appendix here.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.