Financial incentives for oil and gas relinquishment

· 9 min read

After declaring bankruptcy in 2022, Sri Lanka’s recent debt restructuring deal is looking to fully revitalise the South Asian island nation’s economy. While oil and gas partnerships with neighbouring countries are being targeted, there may be opportunities to deliver a more sustainable and equitable path to redevelopment. However, a recent history of violence and political uncertainty leaves Sri Lankan communities questioning the ability to achieve such a turnaround.

A combination of government mismanagement, the effects of COVID-19 and the devastating Easter Sunday 2019 terrorist attacks led to Sri Lanka’s economic crisis1. With a rapid decline in foreign exchange reserves, the country was unable to pay for essential imports like fuel. This inflicted another difficult period upon the communities, who faced daily power outages and scarce supplies of food or medicine. With the poverty rate doubling to 25% between 2021 and 2022, the impacts disproportionately affected women2. Therefore, while the 2023 IMF $3bn bailout has sought to restore growth to the economy, it is vital that this promotes socially sustainable and inclusive outcomes.

A significant portion of the country’s energy mix comes from imported oil (~40%)3. The ramping up of domestic oil production is viewed as an opportunity to attract foreign investment, thereby stabilising Sri Lanka’s faltering economy and generating support for the September election. While exploration of Sri Lanka’s oil and gas reserves started over 40 years ago, this has been disrupted by the 25-year civil war as well as a variety of legal back-and-forth (such as the recent Serendive Energy case in the Court of Appeals).

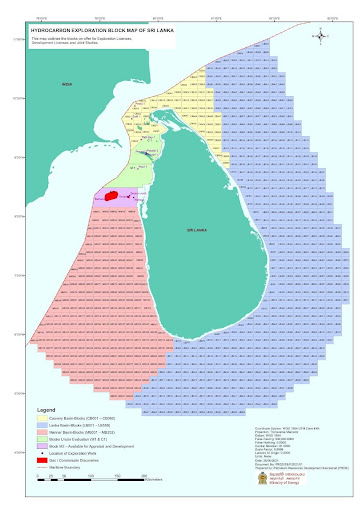

After the approval of new exploration rules last year and the Petroleum Development Authority of Sri Lanka’s (PDASL) identification of about 900 offshore blocks (see Fig.1), there is rejuvenated foreign interest in the valuable natural resources – with claims of 267 billion US dollars’ worth existing under the country’s seas4. India provided considerable financial assistance to Sri Lanka in recent years and is seeking to build on this relationship with a proposed fuel pipeline and other ‘connectivity’ projects . Meanwhile, China is set to compete under the name of state-owned Sinopec and its $4.5bn refinery investment in Hambantota port.

On the verge of risking carbon lock-in (see LEAVIT article) with potential oil extraction projects, Sri Lanka has the opportunity to double down on its renewable energy commitments and support energy security and energy access through the expansion of hydro, solar and wind. Sri Lanka has outlined their 2030 goal of 70% power generation from renewables. Highlighting the potential for foreign investment/partnerships here, India’s Adani Green Energy’s $1bn investment will be directed towards establishing two Sri Lankan wind farms with a combined capacity of 484MW5.

Figure 1 – Sri Lanka Exploration Block Map

(Source: Petroleum Resources Development Secretariat (PRDS), 2021)

Sri Lanka’s Petroleum Resources Development Secretariat (PRDS) has outlined new opportunities for investors to apply for customised groups of blocks. Figure 1 highlights former exploration sites and gas discoveries in the north-west of Sri Lanka shores, but they are also opening up other offshore areas for exploration - including the Cauvery, South Lanka, and East Lanka basins - in a series of licensing rounds. With claims that “the Mannar Basin alone could have the potential to generate five billion barrels of oil and nine trillion cubic feet of natural gas”6, the exploration and extraction within all charted blocks could induce several damaging consequences for the island nation.

There are certain geopolitical considerations for Sri Lanka. The country has historically held ties to multiple global powers and further tensions may arise as they invite competition for exploration projects. The Sri Lankan energy sector is experiencing advances from Europe, India and China. Although this can be largely considered a positive step in rejuvenating the economy and facilitating trade, opening up oil exploration may heighten the risk of encroachment and leave Sri Lanka exposed to external influences over its domestic policies.

While one could correctly point to clean energy investments also introducing geopolitical concerns, the nature of the oil and gas industry can make it relatively more risky in this regard. (Typically) higher capital expenditures can create a deep entrenchment for investors and the host country. Complex contracts like production-sharing agreements (PSAs) or joint ventures can deeply integrate foreign investors with the host nation's economy and resources. Additionally, O&G investments can create a dependency on a single or few suppliers, which can be risky if geopolitical relationships deteriorate. In contrast, renewable energy sources like wind and solar may be more diversified and locally controlled, reducing the risks associated with foreign dependency.

Pollution is of course another serious concern in relation to Sri Lankan offshore oil development. The country’s coastal and marine ecosystem would be exposed to increasing risks of oil spills7. A 2020 report on the BP Deepwater Horizon explosion highlighted how “tourism and oil spills do not mix”8 and with the tourism industry serving as such a vital economic resource in Sri Lanka, an incident even a fraction of this scale could prove disastrous. It should be noted that Sri Lankan authorities have improved regulation and detection measures surrounding spills (seen with the recent introduction of MEPA’s new satellite imagery, verifying a stain measuring almost seven miles in length). However, it is not just oil spills but also the risk of habitat altercation/destruction. These are risks which can inflict long-term damages for relatively short-term benefits.

Stranded assets are those which will suffer from premature devaluations or conversion to liabilities before the end of its economic lifetime, which may be relevant for oil and gas ventures in the context of the clean energy transition. This outcome would impact Sri Lanka through revenue losses via production-sharing agreements or taxation, as well as missed diversification opportunities (expanding the clean energy mix).

The United Nations has noted the disproportionate impact of a worsening climate crisis - “being a tropical island in the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka has consistently been placed among the top ten countries at risk of extreme weather events by the Global Climate Risk Index”9. Sri Lanka accounts for a 0.1% share of global emissions and is ranked 114th globally, in terms of emissions per capita .

It cannot be reasonably expected that the island nation carries the same climate burden that developed countries have historically abused, for their own economic and social betterment. Adhering to ‘fair share’ principles and recognising that developing countries leapfrogging to renewable/clean technologies comes at a cost, innovative climate finance solutions are needed to financially help Sri Lanka transition away from O&G extraction

LEAVIT is a pioneering initiative exploring the use of climate finance incentives to financially incentivize resource-cursed oil-producing countries for relinquishing oil development. Sri Lanka has been identified as a potential beneficiary of these incentives.

Sri Lanka could utilize a debt-for-climate swap targeting its International Sovereign Bonds (around 40% of sovereign debt) by structuring a deal similar to the innovative financial model used in Belize with The Nature Conservancy.

A development finance institution, such as the U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC), could offer credit enhancement and political risk insurance to facilitate a low-risk loan for Sri Lanka. This would allow a newly created investment entity, backed by international climate financiers (like TNC), to issue green or climate bonds at favourable rates, raising the capital needed to buy back ISBs from bondholders at a significant discount.

This mechanism would substantially lower Sri Lanka’s credit risk and financing costs, enabling the country to repurchase and retire a portion of its ISBs at a reduced price. In exchange, Sri Lanka would commit to permanently relinquishing future oil and gas extraction rights and redirecting resources toward renewable energy and climate resilience. Over time, this structure could unlock substantial climate funding, similar to Belize’s creation of $180 million for conservation, while reducing Sri Lanka’s debt burden and reinforcing its leadership in global climate action.

The IMF sees debt-for-climate swaps as less efficient than conditional grants or broad debt restructuring, as they benefit non-participating creditors and may not offer as much fiscal support. However, they can be advantageous in specific cases where they make climate commitments senior to debt service or when broader debt restructuring could cause major economic disruptions10.

While this type of debt-for-climate swap is not yet in place, there is a significant window of opportunity for Sri Lankan officials to propose and advocate for it, given the country's ongoing debt challenges and the pressing need to phase out future oil and gas development. By capitalizing on this moment, Sri Lanka could position itself as a leader in innovative climate finance solutions, while addressing both its financial vulnerabilities and climate commitments.

The first global stocktake (GST) under the Paris Agreement concluded at the 28th UN Climate Change Conference (COP 28) in Dubai with a call on parties to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner”. This marks a historic milestone but as UN climate chief Simon Stiell said this pledge is a “lifeline, not a finish line”. Governments are set to submit their third generation of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) in 2025, marking the first update since the landmark COP 28 agreement to transition away from fossil fuels. These new NDCs should align with the COP 28 commitment, ensuring a managed and gradual phase-out of fossil fuel production to meet Paris Agreement goals.

Climate negotiations face two primary dilemmas: the simultaneous need to reduce fossil fuel consumption and extraction, and the challenge of funding energy transitions in the Global South. Countries in the Global South express frustration over demands to halt fossil fuel extraction, especially when developed nations continue to issue new extraction licenses, fail to provide adequate financial support, and overlook the critical role fossil fuel revenues play in their economic and social development. By introducing an innovative climate finance mechanism that allows for the cessation of oil and gas development while simultaneously reducing sovereign debt and maintaining economic and social development, Sri Lanka could position itself as a leader in climate action. This pioneering approach would enhance the country's international standing, potentially boosting tourism and attracting foreign investment.

Many other Global South countries are encountering similar challenges, with oil and gas extraction becoming increasingly risky and financial incentives for a transition remaining insufficient. Sri Lanka could take the lead by partnering with countries like Timor-Leste, Colombia, and Namibia to form a coalition. This united front could advocate effectively to Global North donors for the necessary support to facilitate a transition away from fossil fuels.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

https://www.iea.org/countries/sri-lanka/energy-mix

https://economynext.com/sri-lanka-ups-oil-resource-claims-to-us267bn-85920/

https://www.power-technology.com/news/adani-green-energy-wind-farms-sri-lanka/?cf-view

https://legacy.export.gov/article?id=Sri-Lanka-Oil-and-Gas

https://srilanka.un.org/en/254230-fact-sheet-climate-impact-sri-lanka

illuminem briefings

Hydrogen · Energy

illuminem briefings

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

Vincent Ruinet

Power Grid · Power & Utilities

World Economic Forum

Renewables · Energy

Financial Times

Energy Sources · Energy Management & Efficiency

Hydrogen Council

Hydrogen · Corporate Governance