From Carbon Neutrality to Climate Neutrality

· 4 min read

The first time I put together a visual on net-zero vocabulary was back in 2019. That slide went on to have a life of its own and was used in presentations by climate policy experts and as a learning tool for a wide range of stakeholders. Things have changed over the last couple of years and it is time for an update.

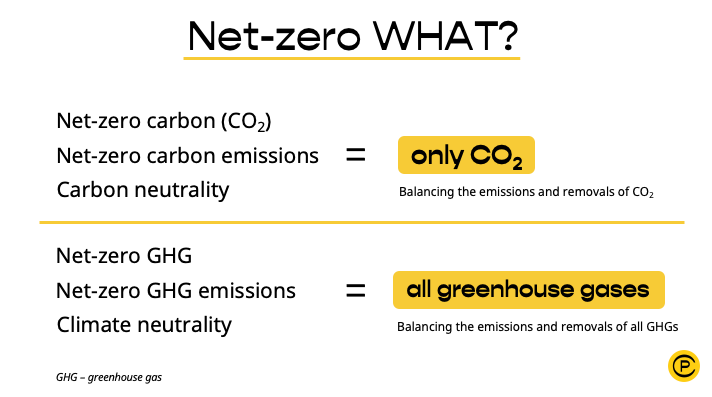

Whenever net-zero targets are used, we have to understand what kind of targets these are. Net-zero as a headline target is vague. That is where the question “Net-zero what?” is coming from. When countries first started announcing their net-zero targets, one of the big questions [1] was whether these targets covered only carbon dioxide emissions or all greenhouse gases (GHGs) – carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, F-gases and SF6.

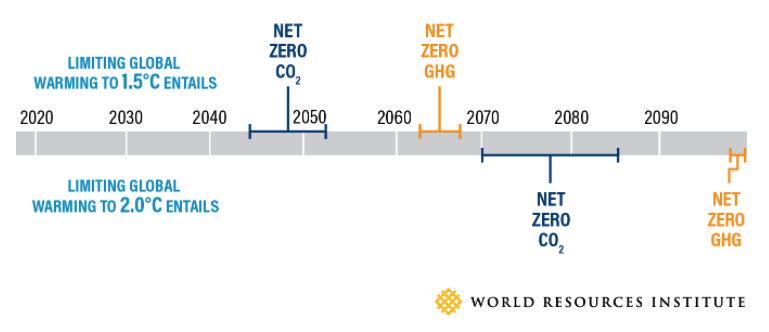

Why is it important to know whether targets cover only CO2 or all GHGs? Because this makes a huge difference in climate ambition. WRI’s graph below illustrates that the timeline between net-zero carbon and net-zero GHG emissions can be 15-20 years, or even more when looking at targets further away. For example, the EU has taken on a climate neutrality target by 2050. This means that it will be carbon neutral already around 2040.

There is still some confusion around how these terms are used.

In 2019 when China’s Xi Jinping first announced the carbon neutrality target by 2060, it seemed to mean what the headline target said – carbon neutrality. Only CO2 coverage. Which translates into climate neutrality sometime around 2080. After almost a year of confusion, in the summer of 2020, China’s special envoy for climate change affairs Xie Zhenhua confirmed that this target actually includes all greenhouse gases. This is an example where a country uses the term carbon neutrality with the meaning of climate neutrality.

A different example comes from the IEA. Their landmark Net Zero by 2050 report only includes CO2, despite the fact that the majority of net-zero targets and literature by now use this term as a short for net-zero GHG emissions.

Whilst the simplified approach visualised above works for many purposes, there is more to how these terms have been defined in practice. Carbon neutrality and net-zero CO2 emissions are equivalent terms on a global scale. The scope of climate neutrality, however, is slightly wider than that of net-zero GHG emissions.

“Although climate neutrality is sometimes used interchangeably with the term net-zero emissions, there is a subtle difference between the terms. Net-zero emissions refers to balancing anthropogenic GHG emissions released into the atmosphere with removals of these emissions over a specified period whereas climate neutrality refers to the balancing of residual emissions with removals and takes into account wider biogeophysical effects of human activities on the climate system overall.”

Jeudy-Hugo, S., L. Lo Re and C. Falduto (2021), “Understanding countries’ net-zero emissions targets”

The same report elaborates further: there is a difference between how net-zero CO2 emissions and net-zero GHG emissions are applied at global vs the regional, national and sub-national levels. For the latter, these terms generally apply to emissions and removals under the direct responsibility of the reporting entity. Carbon and climate neutrality, however, include emissions and removals within and beyond the direct responsibility of the reporting entity.

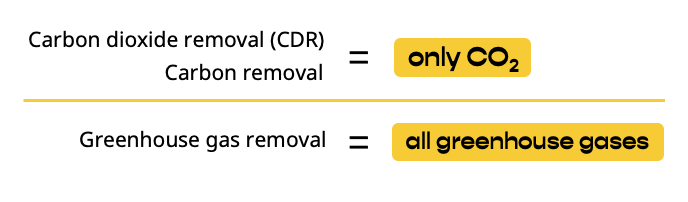

If we zoom into the “balancing” part of the net-zero goals, one would assume that when talking about net-zero (GHG) emission targets, we’d also be talking about GHG removal. In practice, carbon removal is used much more widely than GHG removal.

Greenhouse gas removal is a broader term compared to carbon removal. It covers the removal of all greenhouse gases, including CO2. Of all GHG removals, carbon removal (or its longer version Carbon Dioxide Removal, CDR) is the main type of GHG removal currently explored. This is due to the relative abundance of CO2, its long atmospheric lifetime, and its chemical reactivity which make CO2 an appealing candidate for removal. The IPCC focuses on carbon removal, and so does the majority of governmental policies and academic literature. But GHG removal is also used. One of the most well-known examples to the general public might be the UK’s plans for GHG removals. The EU, in comparison, is preparing its Carbon Removal Certification.

The confusion around the terminology has decreased in the last few years. It’s less and less common to hear speeches by high-level officials that mix up CO2-only targets with climate neutrality targets. Nevertheless, it still remains important to pay attention to the types of net-zero targets and pathways when modelling (be it CO2-only or all GHGs). The question “Net-zero what?” helps to understand each other in climate discussions and compare apples with apples.

This article is also published on the author's blog. Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

[1] there are several other elements that are equally important in net-zero targets.

Aaron Bruckbauer

Pollution · Greenwashing

Jesse Scott

Carbon Market · Carbon Regulations

Glen Jordan

Sustainable Lifestyle · Sustainable Living

Inside Climate News

Pollution · Nature

The Jerusalem Post

Biodiversity · Climate Change

earth.com

Climate Change · Effects