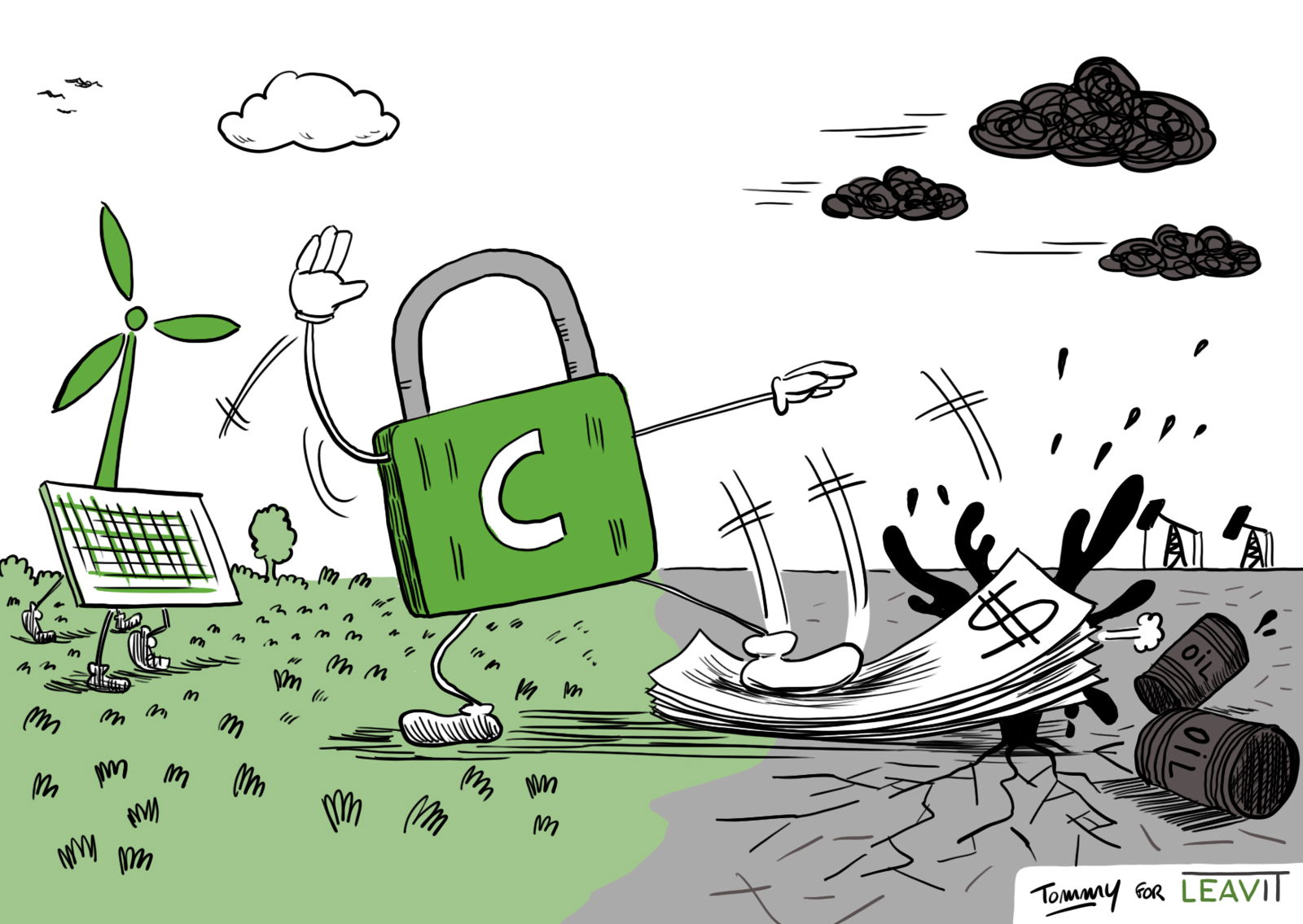

Defusing carbon bombs with climate finance

· 6 min read

The currently existing reserves of fossil fuels contain enough carbon to cause the Earth's temperature to rise well beyond 2°C. Achieving a significant reduction in the demand for fossil fuels is incompatible with the constant increase in supply. All efforts to mitigate climate change are futile unless the valves controlling fossil fuel extraction are actively closed. We need to address the supply side as well, a task that has been largely overlooked until now.

The carbon budget for limiting global warming to 1.5°C is shrinking rapidly, and still the potential emissions from existing fossil fuel reserves far exceed this limit. The statistics are alarming: as of 2023, the remaining carbon budget to limit global warming to 1.5°C is 380 Gt of CO2 emissions, while developed fossil fuel reserves could potentially contribute 915 Gt if fully extracted and burned (Oil Change International).

Let that fact detonate.

There are 2.5 times more fossil fuel extraction projects underway than necessary to stay under the 1.5°C limit. The current trajectory spells disaster, with far more extraction projects in progress than what is sustainable for our climate goals. We're faced with three clear scenarios, each with its own consequences, but only one path forward is truly viable:

Unacceptable: Exceeding the 2°C threshold will threaten our planet's stability and jeopardize the well-being of present and future generations.

Implausible: Wishing for a drastic reduction without constraining demand is like asking an alcoholic to stop drinking and bringing him another bottle.

Indispensable: The only way to stay below 1.5°C is to leave 60% of developed fossil fuel underground (Oil Change International) and the only way to do that is through financial decommission and financial compensation.

So, why does everyone either downplay the severity of Scenario 1 or pretend Scenario 2 is plausible? Why aren't more people working on Scenario 3?

For the past 30 years, efforts have predominantly concentrated on reducing demand, focusing on emissions, and overlooking the production gap paradox of the equation. The 2023 Production Gap Report shows that governments, up to and including 2023, continue to plan for more than double the amount of fossil fuels than would be consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Their approach shifts blame onto consumers while allowing industry to escape accountability in the form of necessary compulsory measures.

Tackling the problem requires a paradigm shift akin to breaking free from addiction. The crucial first step involves severing ties with the source: 'breaking up' with the dealer, steering clear of casinos and so forth. The genuine work of conquering the cravings commences once those ties are severed. We're hooked on fossil fuels and perilously assume we can kick the habit without cutting off the source. Reducing the demand for fossil fuels without concurrently addressing the supply is akin to instructing an alcoholic to quit drinking while handing them a fresh bottle.

A pivotal force in countering new oil development projects stems from the mobilization of frontline activists, indigenous peoples, and civil society organizations. A compelling example is the Stop EACOP campaign, where communities in Uganda and Tanzania, alongside global allies, successfully influenced several international banks and insurers to withdraw funding from the East African Crude Oil Pipeline. Similarly, the recent ConocoPhillips Willow Project in Alaska has triggered a surge of resistance on social media encouraging the signing of petitions with the most popular petition amassing 3 million signatures.

While civil mobilization has had some success in halting specific projects, the financial incentives in the oil industry remain overwhelming. In March 2023, the Biden administration, brushing aside climate concerns and campaign promises, approved the Willow Project for economic reasons and EACOP Joint Venture partners have found Middle East and Chinese financial partners and have started building the pipeline in 2024.

Given the substantial financial stakes in the oil industry, clearly only a new form of financial compensation is necessary to encourage governments to reconsider drilling. It prompts us to explore innovative methods, such as providing financial incentives to oil producing countries to leave carbon permanently in the ground.

Financial incentives to encourage countries to transition away from oil extraction are not applicable to all producing nations. Given their existing wealth, prolonged reliance on oil royalties and substantial contributions to CO2 emissions, providing financial support to oil extracting countries might not be logical. This applies to states such as Qatar, the Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Russia, or even Canada. Inherently, they should undertake the necessary action without external compensation.

Financial incentives to encourage countries to transition away from oil extraction are not applicable to all producing nations. To ensure the initiative remains pertinent, it must align with the principles of a just transition. Prioritizing countries involves considering factors such as historical climate change contribution, economic dependency on oil, overall economic and social development, and vulnerability to climate change. While some countries may not require external incentives due to their wealth and resources, others face significant challenges in breaking free from reliance on oil revenue. More specifically, oil-producing nations grappling with the resource curse and sunk cost fallacy and seeking alternatives to exit from extraction, such as Timor Leste, Columbia, and Chile, should be prioritized.

In 2007, President Correa asked the international community for $3.6 billion in exchange for not drilling 900 million barrels in the most biologically diverse hotspot on the planet. This initiative, initially promising carbon budgeting, was praised by researchers, environmental groups and prestigious leaders but only collected $13 million.

Despite its shortcomings and eventual failure, the Yasuni initiative offers valuable lessons for future endeavors. The Yasuni initiative faced significant challenges leading to its failure, stemming from five core issues. Firstly, Ecuador's 2008 constitution posed a barrier to the concept of additionality by protecting Yasuni from "all types of extractive industries." Secondly, the presence of hypocrisy was apparent as another site, Santa Cecilia, was actively being developed just north of Yasuni. Thirdly, the initiative suffered from a lack of solid structure, relying on funding from diverse and scattered donors who often made non-committal pledges or purchased intangible Yasuni Guarantee Certificates. The presence of moral hazards was exacerbated by Correa's threats to drill when targets weren't met, creating an environmental blackmail scenario and fostering skepticism regarding Ecuador's commitment to keeping oil underground. Finally, European countries sought tangible and immediate outcomes for their donations, contributing to the challenge of paying a heavy price for pacing issues.

While the failure of this initiative has seemingly discouraged all future innovations in supply-side climate measures, the mere existence and brief implementation of the proposal can be seen as a qualified victory.

Leavit's mission to provide financial support to oil-producing nations offers a promising path forward. By leveraging climate finance, countries can be incentivized and compensated for the preservation of carbon in the ground and the transition towards low-carbon, resilient economies. In other words, building upon past initiatives like the Yasuni ITT Initiative with modernised international financial tools and cooperation mechanisms.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Olaoluwa John Adeleke

Human Rights · Environmental Rights

Gokul Shekar

Energy Transition · Energy

Philipp Petry

AI · Power Grid

Financial Times

LNG · Oil & Gas

SolarQuarter

Energy Transition · Energy

The Guardian

Renewables · Solar