Carbon Removal Governance: Lessons from fracking

· 5 min read

Lessons from Fracking: The need for dedicated CDR governance and regulation incorporating an anticipatory approach - one which is inclusive, proactive and innovative.

In a series of previous blogs, we highlighted the extent to which the UK carbon removal sector needed to develop and scale by orders of magnitude - as well as the need to bring society together to manage amongst other issues the potential for market transition risk.

This process of carbon removal - also known as negative emissions - is an essential part of achieving net zero and eventually net negative emissions, both to offset the most persistent remaining emissions, and eventually to bring back down the concentration of CO2 in the air to more sustainable levels.

In a paper published last week colleagues explored how the technology and processes associated with fracking for the production of shale gas were introduced to the UK 10 years ago. We analysed lessons relevant to the establishment and governance of CDR in the coming decades. Fracking was `rolled-out’ in the Lancashire region in a top down manner, by-passing the communities where the technology would be deployed in any decision making role or even input, and chose to retro-fit existing conventional oil and gas regulatory mechanisms to the new technology. The UK’s favourable shale gas potential started to be explored by Cuadrilla Resources in 2011 but earth tremors halted exploration on multiple occasions whilst these were investigated. With limited community engagement, poor transparency and a breakdown in trust increased local opposition and resulted in Cuadrilla abandoning its plans in February 2022.

This has important lessons as a function of the speed with which CDR needs to be deployed. In the UK, it will be a new set of never-been-deployed technologies which will make up an infrastructure sector the size of the water industry in 28 years. At such a scale it will have to be retrofitted into existing communities and networks. This will invariably open up a whole set of intricate, subtle and complex issues - such as a fragmented regulatory landscape, local cultures and multi-sectoral practices, some of which will likely be conflicting. CDR’s impacts and governance processes will be uncertain, untested and highly emergent.

The work that we have been undertaking at the Carbon Removal Centre has emphasised that the UK needs to build a high integrity carbon removal sector from the bottom up - in a way in which all voices are heard, and the results benefit everyone. This will enable the technical development of CDR systems and their associated value chains to co-evolve with socio-political aspects, to create the appropriate enabling environment for CDR to diffuse and scale. So how do you develop an effective approach for new technologies such as CDR to deliver social acceptance based on building and retaining public trust?

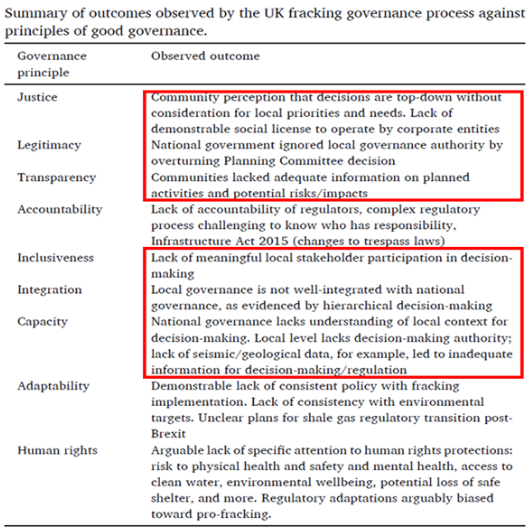

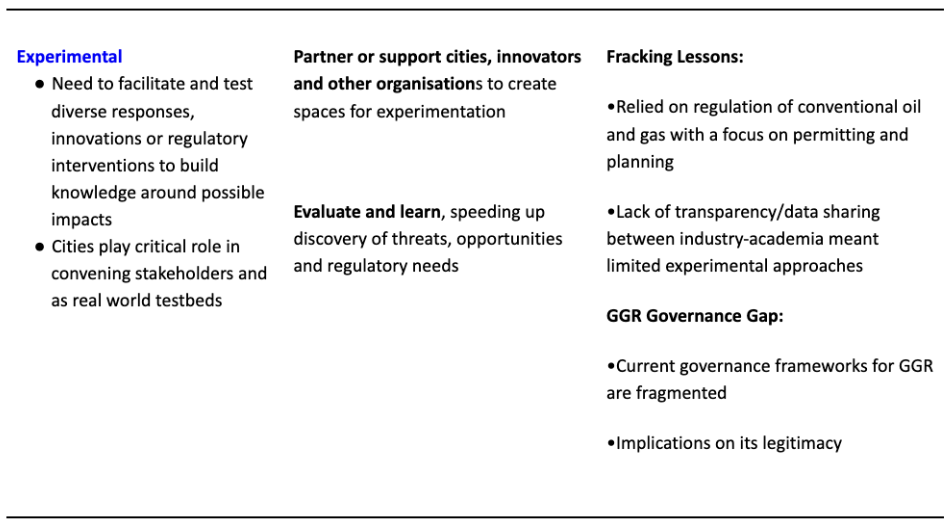

The paper advocates two underpinning tenets. The first is the adherence to the Aarhus Convention (UNECE Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision Making, and Access to Justice in Environmental matters) and the good governance principles[1] which, as the table extracted from the research highlights, were not adhered to in Lancashire during the development of fracking. The second is the need to adopt an Anticipatory Regulation approach[2] i.e., develop a future-facing governance framework for CDR. The figure below from Nesta’s work on this topic identifies three different roles for the regulator, based on the appropriateness of existing regulation for the management of new technologies. These include an:

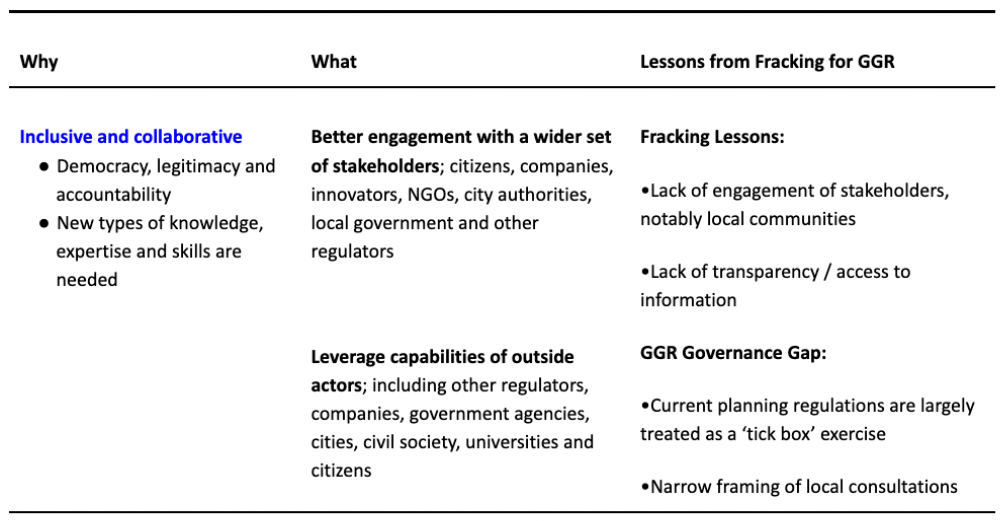

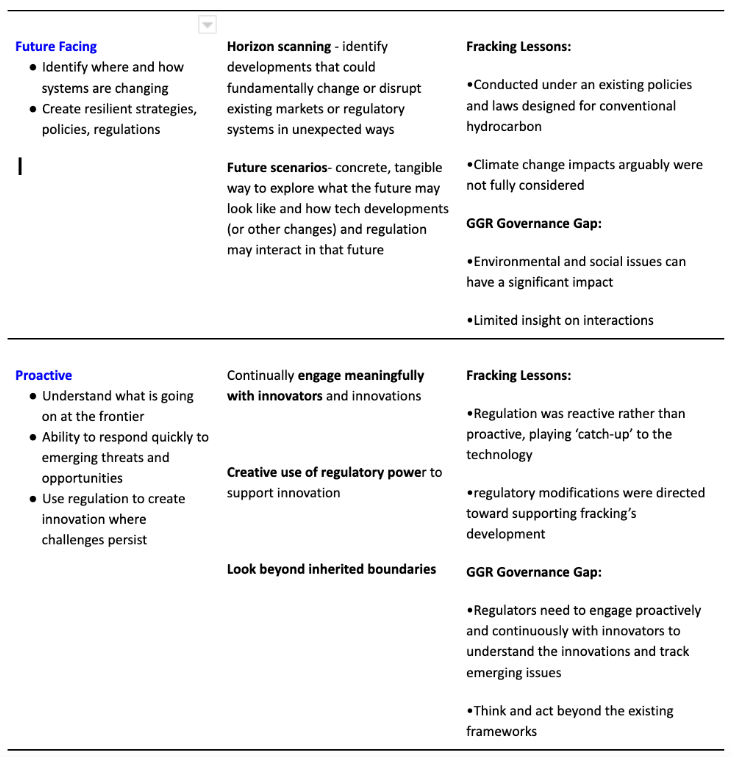

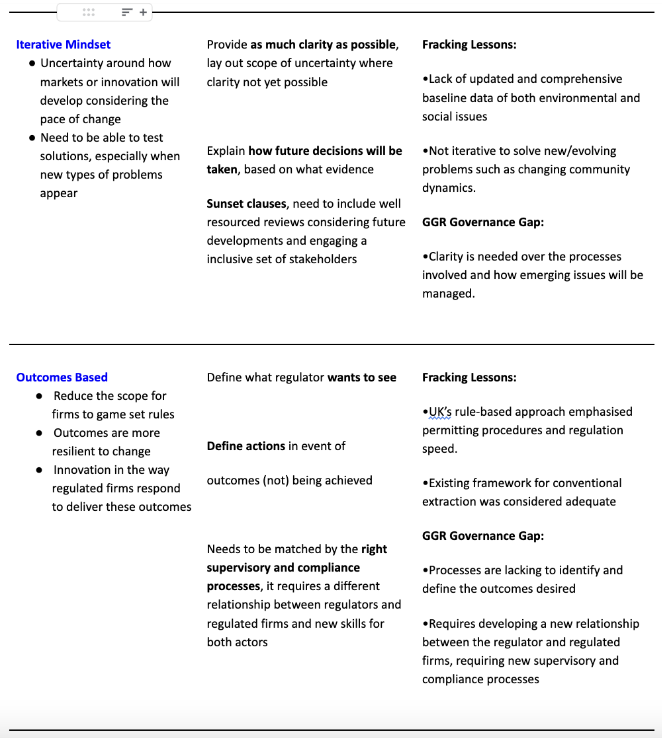

The research found that the current governance frameworks make little provision for engaging stakeholders in the planning and development of CDR. The table below describes the key elements critical for developing Anticipatory Regulation and their compliance with the Aarhus Convention and good governance principles, and highlights the lessons drawn from the experience with fracking relevant to GGR regulation.

The study therefore emphasises a number of lessons for the development of CDR in the UK:

In the UK much of the individual components of anticipatory regulation is already happening but it needs to be brought together - see this link[3] - and the cultural hardwiring of embedding anticipatory constructs and principles of good governance will be fundamental by all leaders in all aspects of governance.

This won’t be easy: reality is messy, and the task is daunting. But bringing different actors together around shared societal goals is a crucial step.

Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Biodiversity · Sustainable Lifestyle

Aaron Bruckbauer

Pollution · Greenwashing

Jesse Scott

Carbon Market · Carbon Regulations

The Guardian

Power Grid · Climate Change

NPR

Climate Change · Public Governance

BBC

Biodiversity · Climate Change