Are you preparing for degrowth? And if not, why not?

· 15 min read

What’s your immediate reaction when you hear the term ‘degrowth’? If it’s to instantly dismiss it as nonsense or wishful thinking, it’s worth suspending your disbelief as, chances are, what you’ve heard about it isn’t fair or accurate.

Take an article in last November’s Economist, for example, which painted the aim of degrowth as “reducing the pace of improvements in overall prosperity, or reversing them altogether.” This might indeed be cause for concern, if it were true. However, not only is it a woefully (wilfully?) inaccurate depiction; the implication that our current economic system is equitably and sustainably provisioning for a widespread increase in people’s capacity to thrive sits in stark contrast to the findings of the latest World Inequality Report.

Such hyperbole isn’t helpful. It risks stoking the kind of polarisation that precludes proper exploration and consideration of our relationship to growth. Is it really the economic necessity we’ve come to believe it is? Or is it perhaps better viewed as a dangerous dependency that business leaders and policymakers should be working to wean themselves off?

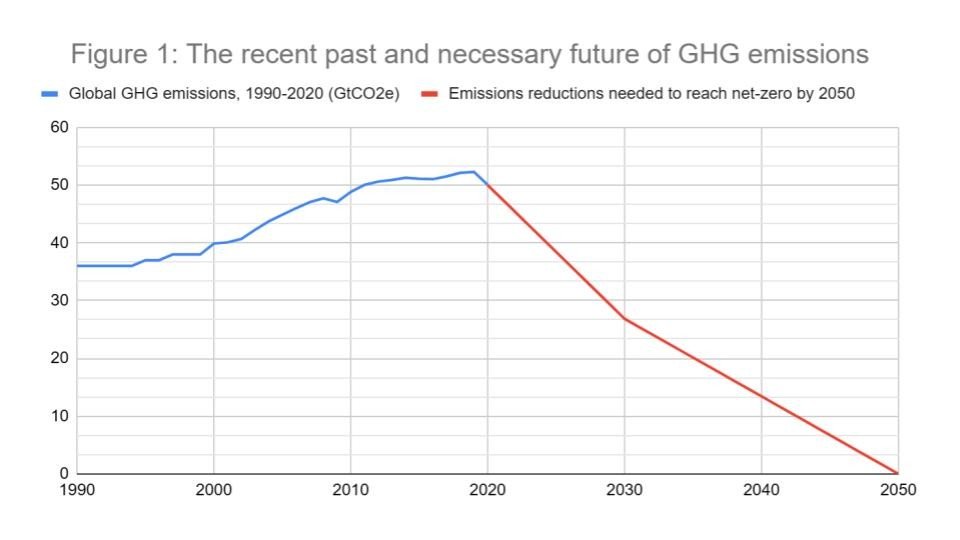

Given the implausibility of green growth alone being sufficient to bring economic activity back within planetary thresholds – and the distinct possibility of involuntary collapse if we continue on our present course – businesses would be wise to start taking degrowth much more seriously, and to consider and plan for what it would take to thrive in a post-growth world.

Which is the more absurd idea? The impossibility of transforming the human stories, rules, incentives and predictions that collectively shape the present system? Or the possibility of bending biophysical reality to the necessity – feasibility, even – of endless economic growth?

Lest first appearances deceive, the concept of degrowth is not, in fact, anti-growth. It’s anti-growthism. What it defines itself in opposition to is the intrinsically expansionist nature of our current global economic system – one that, in being rooted in GDP, and the ever-increasing production of monetised goods and services, depends on ever more energy and resources to power those circuits of production. What it’s for is a planned reduction of energy and resource use, thereby bringing the economy back into balance with the living world in a way that reduces inequality and improves wellbeing.

While ‘anti-growth vs. anti-growthism’ might sound like semantics, it’s a vital distinction. Degrowth doesn’t deny or preclude the need for growth in certain sectors or geographies. Quite the contrary, growing incomes and wealth in the Global South is considered not only possible, within fair allocations of resources and emissions, but also necessary to enable all citizens to achieve a life of dignity (above the social foundations of Kate Raworth’s doughnut). Likewise, degrowth has no issue with the growth of sectors and practices that urgently need to be scaled and replicated (e.g., renewable energy, regenerative agriculture) if we’re to supplant more resource-intensive and environmentally destructive modes of production.

Degrowth, then, doesn’t describe a blanket downscaling of economic output. Rather, it specifically centres on a radical reduction in the economic throughput of energy and resources, which necessarily entails a rebalancing of the system. This includes reorienting the focus of sustainable development from insufficiency in low-income communities (particularly in the Global South) toward excessive production and consumption in high-income communities (particularly in the Global North); and from an economic system fuelled by the creation of insatiable wants to one geared toward equitably satisfying sufficient needs.

Considered a necessary phase on the journey toward a steady-state economy that operates within biophysical limits, it’s part of a multi-layered answer to the ultimate predicament of our age: how to reimagine a global economy that’s capable of provisioning for a predicted 9.8b people by 2050, using half as much energy, while simultaneously addressing climate change, biodiversity loss and social inequality. More simply put, it’s part of how we can achieve a decent life for all, within the means of a flourishing planet.

Even allowing for this more nuanced understanding of degrowth, there are no doubt many who still find the idea unpalatable or unworkable. But which is the more absurd idea? The impossibility of transforming the human stories, rules, incentives and predictions that collectively shape the present system? Or the possibility of bending biophysical reality to the necessity – feasibility, even – of endless economic growth?

Relative decoupling might break the direct correlation between GDP and energy and resource use, but history suggests that, as long as economic growth remains the primary objective, absolute impacts will continue to rise.

As economist and philosopher Kenneth Boulding famously quipped, “Anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

Green growth and degrowth advocates might agree on the ability to relatively decouple emissions, energy use, resource use and biodiversity loss from GDP – even to achieve some level of absolute decoupling. Where they part company, however, is on whether green growth measures alone are capable of achieving sufficient absolute decoupling to bring economic activity back within planetary thresholds – and sufficiently fast to limit abrupt, catastrophic and irreversible change.

Levels of awareness and activity around ‘ESG’ and ‘sustainability’ may never have been higher, but we’re already transgressing six out of nine planetary boundaries and critical metrics continue to trend in entirely the wrong direction:

How can it be that all this is happening, despite business leaders’ and policymakers’ myriad ESG and sustainability commitments?

It’s not hard to see why the finger gets pointed at our fixation with economic growth, when a compound annual growth rate of just 2.5% leads to the economy doubling in size every 30-or-so years. When it would already take more than 1.7 planets to meet current human demand, without running an ecological deficit, that’s clearly unsustainable.

Relative decoupling might break the direct correlation between GDP and energy and resource use, but history suggests that, as long as economic growth remains the primary objective, absolute impacts will continue to rise. As Decoupling debunked, a 2019 report from the European Environment Bureau, explains, the idea that decoupling will allow economic growth to continue, without a rise in environmental pressures, is “highly compromised, if not clearly unrealistic.”

Despite more than 90 years of knowing that economic growth is a poor proxy for progress, leaders still cling to growth as the all-important measure of success. The fact that they do suggests that knowing isn’t enough – that beyond rational argument lie deeper philosophical questions that the science cannot answer.

It’s worth remembering Robert F Kennedy’s famous critique that what we nowadays call GDP measures “everything except that which makes life worthwhile.” And more than three decades earlier, in 1934, Simon Kuznets (the Nobel laureate instrumental in the creation of its progenitor, GNP) warned the US Senate that a nation’s wellbeing could “scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income.”

While we’re often told that economic growth is a prerequisite for addressing poverty and inequality, the reality is that inequality is baked into the present system. The share of global income accruing to the richest 10 percent vs. the poorest 50 percent has remained largely unchanged since 1910. Even during the period 1993-2008, when the incomes of the poorest decile experienced the highest growth, only 5 percent of new income flowed to the poorest 60 percent of humanity, vs. 95 percent going to the richest 40 percent. At this distribution ratio, it would take more than 200 years to eradicate absolute poverty at the level of US$5.00 a day. Furthermore, achieving this would require global GDP to increase by 175 times and global per capita income to rise to US$1.3 million.

In other words, under the present system, it’s impossible to eradicate absolute poverty without laying waste to the planet and creating even more grotesque inequality. Yet, in spite of this analysis – and more than 90 years of knowing that economic growth is a poor proxy for progress – business and political leaders still cling to growth as the all-important measure of success. The fact that they do suggests that knowing isn’t enough – that beyond rational argument lie deeper philosophical questions that all the maths and science above cannot answer.

Imagine for a moment that it were possible to burn as many fossil fuels as we wished, scrape bare as much of the land as we wished, spew as much plastic into the oceans as we wished and, somehow, nature’s sinks would take care of it. Even assuming it were technically feasible, would it be desirable? Is that a world we’d wish for ourselves, our descendants and all other life on Earth?

However you respond to these questions, how aware are you of the worldview that guides you to those answers? Why have we come to see humankind as apart from, rather than part of, nature? What if we spent as much time exploring and appreciating the wonders of natural intelligence as we did extolling the possibilities of AI? How might insights about the ‘wood wide web’, for example, change how we value trees or alter the popular belief that the natural world is more competitive than collaborative? How might the perception of our privilege change if, every time we filled a glass of water, we expressed gratitude for and to that water for sustaining us, and reflected that safely managed drinking water is a basic need to which more than a quarter of our fellow human beings still lack access? In an unequal world, with limited carbon and resource budgets, why shouldn’t we ask who is entitled to consume what?

Having more to do with feeling, intuition and judgement than with rational thought, such questions aren’t typical boardroom fodder, but maybe they should be. They encourage a different way of seeing and being – a story rooted in interdependence, rather than exploitation – that will be vital to businesses’ capacity to survive and thrive over the coming decades and beyond.

Whether or not you believe a paradigm shift is coming, it still makes sense to act as if you do; because, like Pascal’s Wager, the consequences of betting the wrong way are infinitely worse.

Rather than assuming that green growth will allow the present system to continue in perpetuity, we should question both its feasibility and its desirability. In turn, this should open the door to the serious exploration of alternative scenarios, each of which, one way or another, would herald a paradigm shift:

Given the choice between planned transition and involuntary, chaotic collapse, who wouldn’t go for what’s behind door number three? Rather than barely giving a thought to if the cultural hegemony of growth might end, wouldn’t it be smarter to contemplate when and how it might happen, and to figure out how to be prepared for it when it does? In any event, whether or not you believe a paradigm shift is coming, it still makes sense to act as if you do; because, like Pascal’s Wager, the consequences of betting the wrong way are infinitely worse.

If you’re a sustainability consultant, be ready and willing to guide your clients in accordance with emerging new frontiers of sustainability leadership. If you’re a buyer of their services, use your purchasing power to demand that they are.

Instead of dismissing the notion of degrowth out-of-hand, give it the attention it deserves. Approach it with a ‘yes and’ mentality – a necessary build on green growth, in recognition that green growth alone has thus far proven (and is likely to continue to prove) insufficient.

Have your strategy and enterprise risk management teams build post-growth worlds into your scenario planning. Explore how your core competencies might be pivoted toward addressing real-world problems, linked to both the overshoot of planetary thresholds and shortfalls vs. social foundations. Likewise, explore the systemic barriers to your adoption of genuinely regenerative business models and creative ways to overcome them.

Especially if you’re a vendor or buyer of sustainability consulting services, upskill your people in degrowth-related concepts. Whether that’s understanding the landscape of degrowth policy proposals, the characteristics of degrowth-compatible business models, or context-based systems of measurement and reporting (e.g., the UN Sustainable Development Performance Indicators, ‘matereality’ assessment), all can help illuminate the pace and scale of transformation required in order to occupy a just and regenerative operating space.

If you’re a sustainability consultant, be ready and willing to guide your clients in accordance with these emerging new frontiers of sustainability leadership. If you’re a buyer of their services, use your purchasing power to demand that they are.

Start by being willing to explore the origin story of today’s system, to question its ‘reality’ and to unlearn received ways of thinking. Because of what the modern, growth-fuelled economic system has provided (from life-saving antibiotics to motorised transport), it’s become almost sacrilegious to question the social and environmental costs of those gains; but question them we should, especially when those who gain the least suffer the most.

Have you ever opened your mind to the possibility that your success might not be yours alone – that you are, in fact, building on a shared inheritance from nature (her ecosystem functions) and the systems (e.g., legal, communications) built by previous generations? Regarding the latter, have you ever considered, too, that the privilege you enjoy today has its roots in European colonialism? Having the humility to ask and live with these sorts of questions can encourage us to more deeply consider our role as good siblings and ancestors – in every part of our lives – and to reconnect with indigenous wisdom, rooted in reciprocity and kinship with nature. This is vital because, to shift systems, we must first shift ourselves.

When we’ve sensed what is out of alignment, we can more authentically (re)connect the personal with the organisational and systemic. At the organisational level, this includes bringing a more heartfelt perspective to thinking afresh about corporate purpose. What is your business truly in service of? Does its purpose express and help operationalise a genuine commitment to the creation of systems value – to improving the health and vitality of the social and environmental systems, upon which we all depend – or is it ultimately self-serving? If your people, your communities, the natural world and future generations had seats around your board table, would they reach the same conclusion? If they wouldn’t, what would have to change so they did?

As Bucky Fuller famously said, to change the system, don’t fight the existing system; build a new one that renders it obsolete. Experimenting at the edges of core business can provide the necessary freedom to pursue real innovation, aligned with biophysical reality.

Working back from post-growth scenarios, determine what would have to be true for your business to thrive in this environment. Starting from the premise that, in the not-too-distant future, only businesses that help solve the problems of people and planet will be permitted to grow (and even then not without limits), follow the playbook of impact entrepreneurs to develop a prototype ‘D-corp’. For example:

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Benoît Larrouturou

Degrowth · Social Responsibility

Susana Gago

Nature · Degrowth

illuminem briefings

Sustainable Lifestyle · Sustainable Business

Oil Price

Circularity · Battery

World Cement

Circularity · Architecture

Euronews

Green Tech · illuminemX