· 6 min read

As some green taxonomies compromise on gas, China’s own exclusion of fossil fuel electricity projects sends the right market signal

As the urgency for climate action intensifies, momentum is building to support climate-friendly energy investments. But given widespread claims of environmental sustainability, how do we ensure that green-branded businesses and products are true to label and deserving of green energy finance? This is where green taxonomies, if designed properly, can play an important role.

What are green taxonomies?

A taxonomy is a system for categorising things based on their scientific characteristics. A green taxonomy specifies business activities that are low-emitting and environmentally sustainable, and therefore eligible for green finance.

In the energy space, this typically refers to renewables like solar, wind and geothermal. It also specifies the environmental criteria, such as emissions thresholds, that the activity must satisfy to qualify for the green label.

For banks and investors, a taxonomy provides the parameters for what they can and should invest in if they want to call it a green investment. Wanting certainty that they are investing in clean and sustainable technologies, they rely on taxonomies to guide them.

Therefore, a key role of green taxonomies is to efficiently channel and unlock new pools of capital towards proven, environmentally clean and sustainable assets, to address the global climate crisis.

China’s version of a green taxonomy is the Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue.

Why did China and the EU develop a Common Ground Taxonomy?

A flurry of green taxonomies have been published in several markets, including China, the European Union (EU), Malaysia and Russia. More are being developed.

As most taxonomies are tailored to national or regional contexts, the methodology, metrics and technical criteria for what constitutes a green investment can differ significantly from market to market, leading to comparability issues for capital providers. This, in turn, can delay the pace at which private capital is mobilised as investors who are focussed on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues apply caution to what the different taxonomies recognise as green.

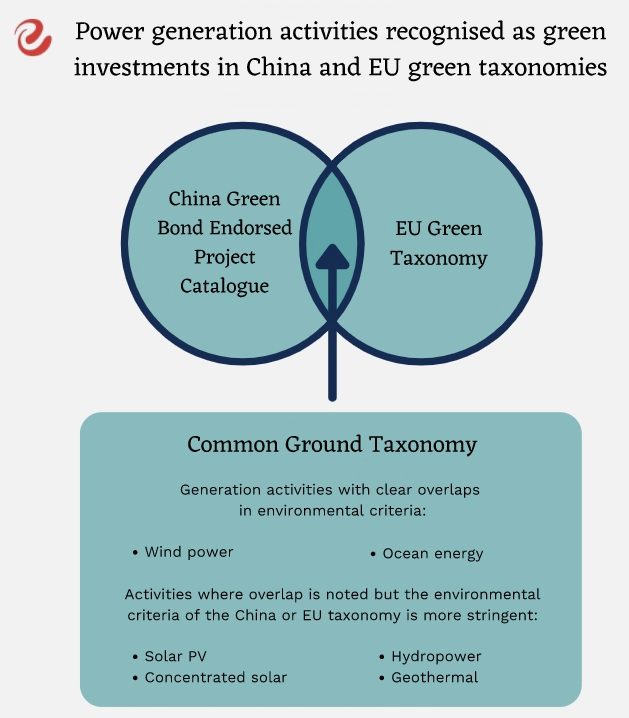

Consequently, China and the EU initiated a comparison exercise of their respective taxonomies to identify commonalities and differences. The Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT) is the initial phase under the initiative and is undergoing due process – which involves a public consultation through this month.

The CGT, while it has been viewed as a harmonisation program, does not create a “common” or “single” taxonomy. It does not have legal effect and is not formally endorsed by China or the EU.

As such, once finalised, the CGT simply assists capital providers in determining which asset or project would or would not be accepted as a green investment in both China and the EU. Other jurisdictions could also use it when developing their own taxonomies, for example, by identifying the activity and technical criteria commonly recognised in both markets to achieve alignment.

The problem with taxonomies

Taxonomies and their usefulness are linked to their accuracy, which is influenced by politics and lobbying. In October 2021, after six months of resisting industry calls, the South Korean government caved and added liquefied natural gas (LNG) to its near-final green taxonomy.

Likewise, in November 2021, the European Commission signalled that the bloc is considering a role for gas in the EU green taxonomy. Other Asian markets have indicated similar intentions, meaning gas or LNG would qualify for green bonds and loans under these taxonomies.

The gas industry can continue to raise funds through the traditional debt market, though the push by lobbyists for gas to be recognised as environmentally “sustainable” in both the EU and Asia indicates that gas corporations can see into their shrinking future. They are fighting for a place in the rapidly growing sustainable finance universe to expand their sources of capital – and potentially lower borrowing costs.

Policymakers have carved a role for gas in the energy transition in some markets. However, even if gas has a role in decarbonising the economy to wean markets off coal, it should not be validated as a green investment.

In addition to coal, gas is a fossil fuel that contributes carbon and methane to the atmosphere, with lifecycle emissions that are dangerous and significantly worse for the climate than coal in the short term.

Green taxonomies do not limit the energy mix. The absence of gas-powered generation from taxonomies does not prevent it from being considered in decarbonisation plans.

If gas-fired power is recognised as green, ESG-focussed investors may find themselves inadvertently backing the high methane and carbon fuel and risk being accused of greenwashing. This in turn risks undermining investors’ trust and the purpose of green taxonomies.

Reacting to the EU debate on the inclusion of gas in its green taxonomy, a leaked document from the UN-backed Net-zero Asset Owner Alliance, representing about 9 trillion euros of investment, suggested it is against including gas and nuclear technologies in the taxonomy. This was followed by the European Sustainable Investment Forum (EUROSIF), a pan-European sustainable and responsible investment association, warning that including gas in the taxonomy would jeopardise the credibility of the EU’s sustainable finance agenda and its global standing in financial markets.

What does this mean for China?

The addition of gas in green taxonomies in the EU, South Korea and potentially other Asian markets could make room for China to lead in upholding credible green energy financial standards.

Its first green taxonomy in 2015 categorised “clean coal” as a green project that qualified for the issuance of green bonds, drawing widespread criticism, particularly from foreign investors. China has learnt from market trends and adapted and removed fossil fuel electricity-generation projects. Mandatory and improved climate-related disclosures, among other things, are being introduced.

Early this year, the governor of the People’s Bank of China, Yi Gang, stressed that government funding alone would not be sufficient for China to meet its net zero goals – forecast to require an estimated US$22 trillion from 2021 to 2060 – and therefore, market participants must be encouraged to step in and fill the gap.

President Xi Jinping’s pledge to accelerate the country’s transformation to a green and low-carbon economy, and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060, also opened the door to a much more strategic view of how China’s green finance market should develop, and which technologies should be incentivised.

These moves indicate that China is ready to take the reins from the EU – whose green taxonomy was long held as the gold standard – and compete for global green capital. China understands that ESG-focussed investors have become more forensic in their research and decision-making on what the different taxonomies recognise.

Capital providers around the world are urging governments to step up and commit to clear, strong and investable policies that will unlock the capital needed to transition to a net-zero economy.

China has a lot to be proud of with its green taxonomy. As Governor Yi hopes, if it remains strategic, China could see private capital mobilised expeditiously to plug its energy transition financing gap.

This article is also published on IEEFA. Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.