Reducing emissions in the agricultural sector: options for Australia and beyond

· 10 min read

Since its discovery in late 2019, the whole world has been battered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many lives have been lost and different variants of particular strains of the corona virus continue to negatively impact society and the way we live our lives. Yet, for all of its negative consequences, COVID-19 had a welcome side effect for a while. Limiting people’s movements, complete city lockdowns, and the temporary slowing down of the global economy led to a net reduction of 6.4% in global greenhouse gas emissions in 2020. With the recovery from the pandemic, many of the conventional ways of production were resumed and a real pivot to “build back better” was missed.

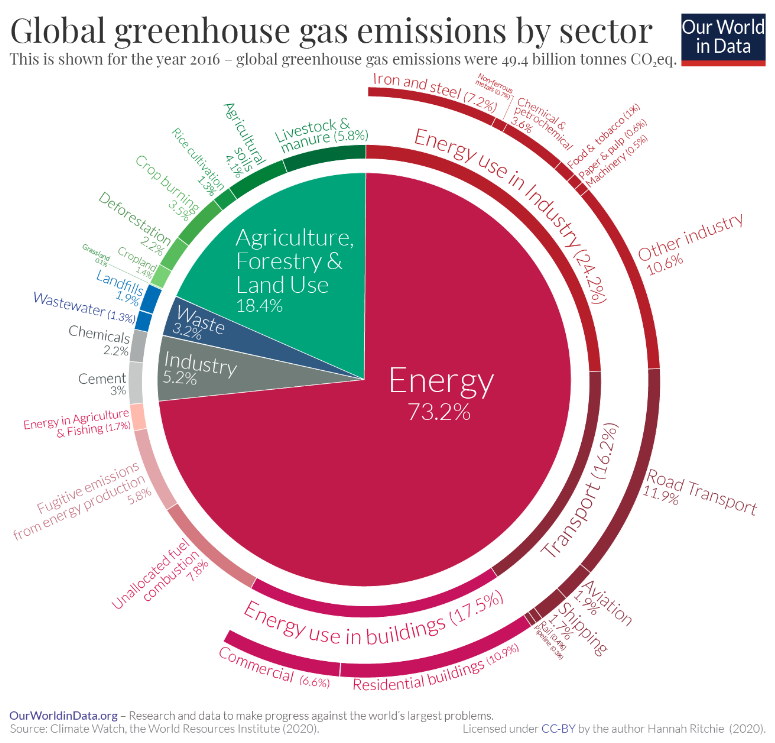

The missed opportunity to “build back better” and the ensuing increase in global emissions was recently further exacerbated by Russia’s war in Ukraine. Russia’s invasion of its Western neighbor led to an uptick in our reliance on fossil fuels, including not only oil and gas, but also coal. While this might only be a temporary setback, it could complicate the transition to a net-zero economy. Efforts are made by major powers in the West to wean themselves from their dependency on Russian energy imports, furthering investments in and the promotion of renewable sources of energy. While energy and transport are the two biggest global sources of emissions, emissions from agriculture, forestry and land use (AFOLU) occupy the third place with a share of 18.4% in 2020.

The AFOLU sector has two main drivers that lead to emissions increases: livestock emissions and emissions related to increased and more intensive land use, especially when linked to deforestation. A growing global human population increasingly relies on animal protein, especially as per capita GDP increases in countries, particularly in developing countries across Asia. Per capita meat consumption has not only increased by 20kg since 1961, more and more humans also mean that this increase is exponential. While efforts to reduce meat consumption are important, even a reduction in how much meat humans eat per day will most likely be offset by unabated population growth, especially in developing countries.

Sustainable practices, such as “meatless Monday” are a good option, as is the general rise in vegetarianism and veganism in many societies. Yet, the growing trend towards lab-grown meats presents its own challenges around, for example, land clearing for soybean growth, increased water use for irrigation, etc., as well as genetic alterations to the DNA of organic matter. More research in this regard is essential, and certainly, a combination of different strategies promises the best results in terms of reducing emissions. As part of this, strategies to reduce emissions in the livestock sector are of fundamental importance.

Brazil, Australia and the USA are the world’s biggest beef exporters. Cattle and sheep are both ruminants, which emit significant amounts of methane into the atmosphere as part of their digestive processes.

My South Pole colleagues Hannes Etter and Jasmin Schwägli recently wrote about “combatting cow burps” and the role of feed additives in reducing emissions from enteric fermentation. With methane being 28 to 36 times more potent in terms of its global warming potential than carbon dioxide, concerted efforts to reduce these emissions from ruminants are an important way to mitigate agricultural emissions. In addition, carbon revenue from emissions reduction projects in this area can play a key role in stimulating the use of practices, feed additives and innovations and make them more mainstream.

Currently, a great deal of research and development goes into identifying and scaling activities in this regard that lend themselves for widespread adoption. Some of these innovations are technology-based, such as using cattle harnesses that are constantly worn by the animal and claim to directly absorb and neutralize methane.

Another promising alternative is livestock feed additives that can be administered to ruminants, particularly in a feedlot environment, where monitoring and verification of the correct administration of the feed additive are more straightforward than in a grazing context. While some of these additives are still in early to advanced stages of development, others are market-ready, waiting to be deployed at a larger scale.

By and large, two types of livestock feed additives can be identified:

1. Enzyme blockers: which suppress methane production through modification of the rumen environment. Examples for enzyme blockers include:

2. Rumen fermentation modifiers: they reduce methane emissions by directly acting on the population of methanogenic archaea (microbes) in the rumen

All of these livestock feed additives potentially qualify for registering an emissions reduction project under VERRA’s methodology VM0041, if they can provide sufficient and peer-reviewed proof of GHG emission reduction potential. Credits generated under such a methodology are considered avoidance credits, since they lead to a reduction in emissions compared to the status quo.

The rapid rise of meat consumption and in consequence, livestock numbers, certainly has detrimental effects on driving up the concentration of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, which is why mitigating these effects via livestock feed additives is of great importance. Yet, there also are various elements related to agricultural production that provide opportunities for decarbonization, both under avoidance methodologies, as well as removal methodologies. The latter refers to activities that result in permanently sequestering greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, e.g. by storing them in the soil.

There is very little evidence that soil organic carbon stocks can be increased in a continuously cropped system. However, there is substantial evidence that this is possible in grazing systems, where livestock play an important role. Grazing management is one of the ways in which soil organic carbon stocks can be increased, one type of which is referred to as regenerative grazing, where cattle are rotated across different paddocks based on a predetermined schedule.

Regenerative grazing has multiple benefits; cattle are not able to graze quite so selectively, which can assist with weed control. Their hooves can stomp plants into the soil, which adds organic matter and exposes it to oxygen, which can help grasses and other more desirable plants take over. Pastures that are actively grazed sequester more carbon, as plant growth is stimulated via the consumption of green growth by the cattle. When cattle are moved on to the next paddock, plants have a chance to regrow.

In the case of perennial species, further soil organic matter is built when these perennials can expand their root systems into the ground, and multi-species mixes provide plant and root diversity. There is increasing recognition that this combination of multi-species perennial plant cultivation with rotational grazing in a free-range environment provides a great opportunity for soil carbon sequestration. This can also mitigate the effect that methane emissions from grazing ruminants have on the atmosphere.

In 2015, the Australian Clean Energy Regulator introduced another method for reducing livestock emissions at the herd level: Beef cattle herd management. Eligible activities under this method for the generation of carbon credits include improved genetics, culling unproductive animals, better fencing and enhanced access to watering points. Some of Australia’s largest beef producers, such as AACo, NAPCO and CPC have taken on this method and generated hundreds of thousands of tons of carbon credits. Yet, this method is also suitable for smaller cattle owners, as it allows to combine different herds into the same project via an aggregation.

When it comes to feedlots,managing animal effluent is a promising methodology for either or a combination of emissions destruction, emissions avoidance and biogas generation, depending on the activities chosen. Manure is captured in an anaerobic digester that is a closed environment that generates biogas. The biogas is captured and can be combusted to destroy the methane component in the biogas, used for energy production, e.g to power a generator, or converted to biomethane for use in the gas grid.

In many cases, agricultural properties consist of a range of different geographical features spanning diverse areas across pastures, gullies, ridges and forests. These parts of such properties can be suitable for different carbon methodologies. It is the combination of these that yield the biggest emissions reductions and, consequently, the biggest potential for generating carbon credits.

A so-called “carbon estimation area” (CEA) can be defined for each methodology. This may also include potential vegetation projects, where native vegetation is allowed to regrow, select species are planted, land is reforested or afforested, or deforestation is avoided in cases where clearing permits had already been issued. The intention of the application of such methods is to reduce the adverse effects of intensified land use and deforestation on the land sector.

In Australia so far, all such methods require the registration of a separate carbon project. This is relatively costly, as a lot of time is spent on documentation of undertaken project activities and related record keeping. In addition, auditor fees and other third party costs are accrued for every single project. This prevents land owners from realizing the full carbon abatement potential of their property.

The Clean Energy Regulator recognized this shortcoming and in October 2021 announced the development of an ‘integrated farm method’, allowing for the combination or “stacking” of different activities from hereto separate methods, all under the same registered project. This “integrated farm method” is supposed to be released in early 2023. It will solve this bureaucratic impasse and unlock significant carbon revenue potential for many landholders.

Finally, there are other opportunities for generating ecosystem benefits when it comes to land management outside of carbon projects. These include biodiversity offsets, where biodiversity projects are developed on marginal lands, for example, to restore gullies to prevent erosion from sediment run-off. The first biodiversity offset compliance markets already exist in Colombia and in New South Wales, Australia. In addition, early signs of interest in biodiversity offsets from voluntary buyers are being picked up, further bolstered by the impending 2022 UN biodiversity COP that is to be held in China. While this presents a significant opportunity, the benefits and trade-offs of developing carbon and biodiversity projects need to be carefully weighed.

To summarize, agricultural emissions contribute significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions. Grazing beef, sheep and dairy are disproportionately responsible in this regard. While a shift in behavior directed to lowering individual meat consumption is important, the continued growth of the world’s human population calls for drastic shifts to the way meat, dairy and crops are produced.

Carbon and also biodiversity projects represent a great opportunity to shift towards more environmentally sustainable and less emissions-intensive modes of production. Revenue generated through the development of climate projects and the subsequent sale of carbon and biodiversity offsets, and other types of payments for results-based ecosystem services, can provide the necessary economic incentive for more broad-scale adoption of related practices, technology innovations and changes in behavior.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Carbon · Environmental Sustainability

illuminem briefings

Carbon Regulations · Public Governance

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

Politico

Climate Change · Agriculture

UN News

Effects · Climate Change

Financial Times

Carbon Market · Public Governance