Why the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism needs rethinking for developing countries

· 10 min read

The proposal for the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) put forth by the European Union (EU) Commission in July 2021, and since approved by the European Parliament on April 18 2023, has come under intense scrutiny worldwide. The CBAM is a unique tariff introduced to level the playing field between EU companies and importers. It imposes an equivalent carbon price on imports of energy-intensive goods as that on domestic goods through the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). However, expecting developing countries to pay the same tariff as far more advanced economies puts an unfair strain on their exports, potentially impacting their development. This may be in violation of the internationally-recognized ‘common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities’ principle that has guided multilateral climate action thus far.

In order to avoid compromising a multilateral approach on climate mitigation and its own development agenda, the EU Commission must design the CBAM in a way that is attuned to the concerns of developing countries. This brief investigates how the CBAM can be designed for greater equity while still meeting its goals of reducing the relocation of EU companies, referred to as carbon leakage, and incentivising non-EU countries to act on mitigation.

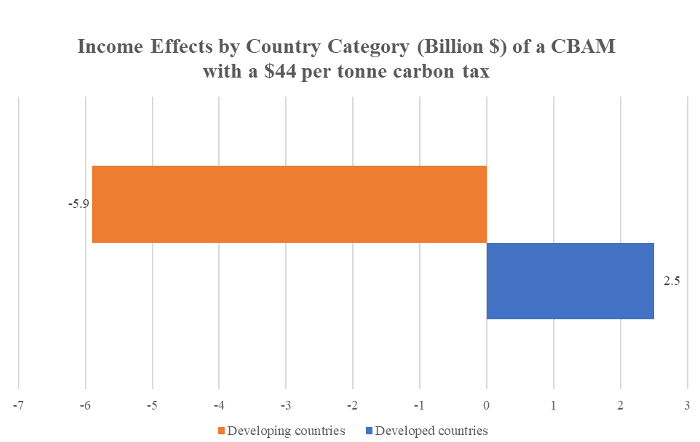

Despite the CBAM’s benefits for the internal economy of the EU, its potential for significant and harmful impacts on the development and welfare of developing countries must not be underestimated, especially for those with a high share of carbon-intensive exports to the EU. Its implementation could result in a drastic reduction in developing countries’ export revenues without necessarily leading to increased sustainability objectives in their national plans (Ameli et al., 2021). Figure 1 shows the discrepancy between the projected income effects of the CBAM on developed and developing countries.

Figure 1. Income Effects by Country Category

Note. Adapted from “A European Union Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Implications for developing countries”, by UNCTAD, 2021, p. 21.

Indeed, Eicke et al. (2021) find that it is African and Asian developing economies that will most likely face the highest tariffs for several reasons. Firstly, developed-world producers tend to use less carbon-intensive production methods in the targeted sectors than their counterparts (UNCTAD, 2021). Secondly, developing countries tend to be more dependent on their trade with the EU compared to more advanced economies. Exports to the EU generally make up a significant chunk of their export revenues, referred to as a high level of exposure to the CBAM. Additionally, developing countries’ exports tend to be less diversified, making it difficult to switch away from the target industries of the CBAM, and resulting in greater vulnerability to the tariff.

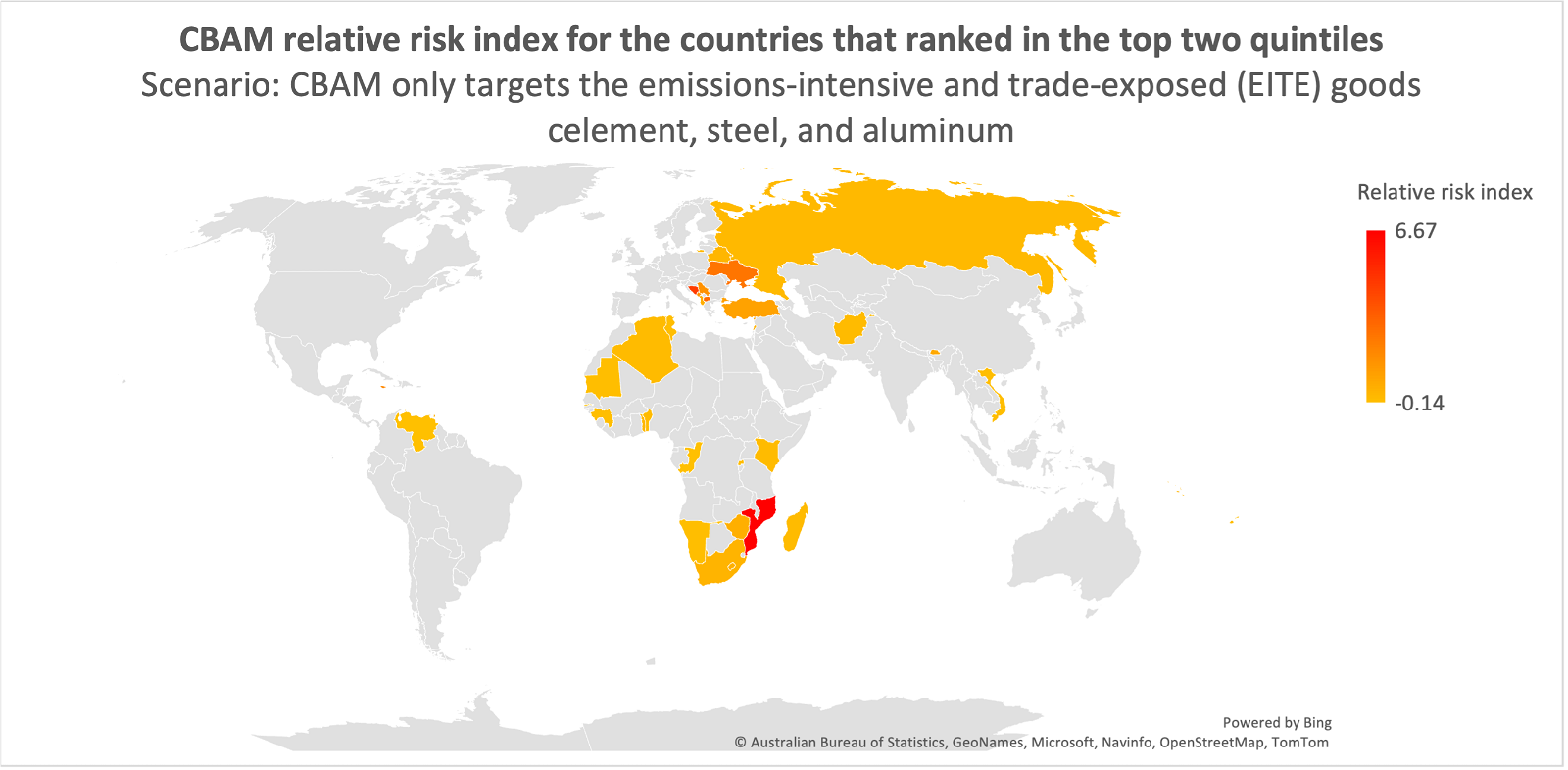

Some Climate Vulnerable Countries (CVCs) have it even worse. Take the case of Mozambique — a Least Developed Country (LDC), the fifth most CVC from 2000-19, and among the economies that are projected to be most impacted by CBAM (Eckstein et al., 2021; Gore et al., 2021). Unfortunately, Mozambique is not alone: Figure 2 shows the impact of the CBAM on the target industries in certain developing, climate-vulnerable countries. (Gore et al., 2021).

Figure 2. Trade Relations between CVCs and the EU

Note. Adapted from “What Can Least Developed Countries and Other Climate Vulnerable Countries Expect from The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)?”, by Gore et al., 2021

Recognizing the need to champion ideas that appeal to the EU legislative bodies, this brief bases its argument on three implications of the current CBAM that may prove detrimental to the EU’s interests. Firstly, developing countries most affected by CBAM and vulnerable to climate change lie in regions of “geostrategic importance” (Hornidge, 2023), that comprise the Middle East, North Africa, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia. Secondly, the EU must recognize that the perception of the CBAM among its stakeholders in the developing world will determine whether it can continue being an international leader in climate action. Finally, compromising the development of these countries could damage the Commission’s own development agenda.

As the data shows, the CBAM will likely disproportionately impact development in LDCs and SIDs that lack the resources to transition to a low-carbon industry without compromising their own development. Additionally, it does not align with the EU’s diplomatic and political interests among developing countries. As such, the adaptation of the CBAM requires the immediate attention of the Commission before the implementation of an indiscriminate tariff in 2026.

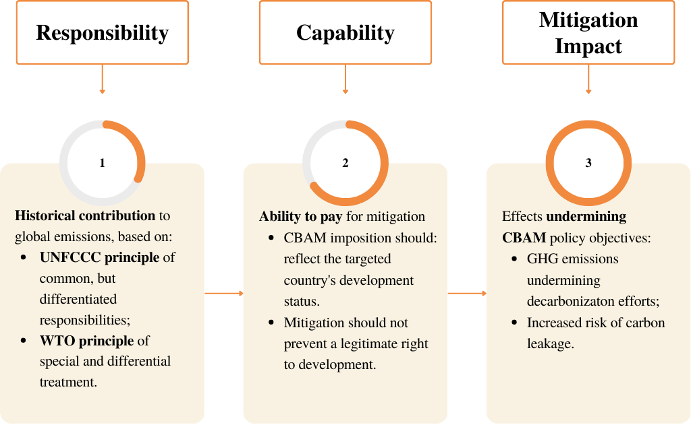

Figure 3. Authors’ criteria to evaluate policy options on the CBAM

Given the information available at the time of writing, this policy brief argues that the CBAM tariff has fallen short of the aforementioned equity rules that would ensure an equitable and inclusive effort to decarbonize. Unequal risk dispersion of the CBAM, both in terms of exposure and vulnerability, may further entrench global inequalities, as highlighted in Figure 4. This policy brief therefore argues for the addition of supplementary measures to reduce the adverse impacts of the CBAM on LDCs and SIDs and avert the threat to their development.

Figure 4. CBAM relative risk index

Note. Adapted from “Pulling up the carbon ladder? Decarbonization, dependence, and third-country risks from the European carbon border adjustment mechanism”, by Eicke et al., 2021.

This brief recommends a three-pronged approach to achieving an inclusive CBAM. Firstly, exemptions should be granted to Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDs). Secondly, the exact nature of these exemptions (partial, conditional or transitory) ought to be determined following a multilateral effort to include these countries in the design of the CBAM. Finally, taking out the administrative costs of the CBAM, the funds raised from it should be redirected to financing the low-carbon transition in these countries.

Such a recommendation satisfies the policy criteria of responsibility since LDCs and SIDs tend to be low historical emitters yet highly vulnerable to the crisis (UNDP, 2023), and capability, since the indiscriminate application of the CBAM imposes an equal cost-sharing burden on all countries. However, it may violate the criterion of mitigation impact. Many scholars argue that exemptions may lead to increased carbon leakage — domestic companies may choose to relocate to countries that receive exemptions. In reality, however, this is unlikely: Lowe (2021) argues that low volumes of LDC imports mean that the risk of carbon leakage should not increase significantly even if they receive a blanket exemption. In the event that it does, however, he argues that the EU can design safeguards to be triggered in the case that domestic companies are affected, through, for example, rule of origin regulations. Additionally, exemptions may also disincentivize developing world countries from decarbonizing. Perdana and Vielle (2022) estimate that exemptions to LDCs may add 47 million tonnes of GHG emissions compared to a scenario in which exemptions are not implemented.

To mitigate this risk, it becomes all the more important to redirect the funds from the CBAM to LDCs and SIDs for the specific purpose of improving their energy efficiency, which Perdana and Vielle (2022) argue would be “affordable for European countries and welfare improving for developing countries.”

Each of the three recommendations is laid out carefully pronged into the EU’s legislative framework.

Firstly, to foster dialogue, the Commission can use the GCCA+ as a platform to consult with LDCs and SIDs and build their capacity in the design of the CBAM.

Secondly, given that the EU applies a legal framework of positive discrimination towards developing countries, granting exemptions only contributes to the consistency of the CBAM within the present EU trade and development policy strategy (Lowe, 2021). Thus, exemptions can be considered a natural extension of the EU’s policies towards LDCs and lower to middle-income countries, based upon the “Everything but Arms” (EBA) Scheme and the EU’s Generalized System of Preferences (GSP and GSP+) targeted toward LDCs and lower to middle-income countries. It follows then that blanket exemptions should be granted to countries covered by the EBA Scheme and that the level of exemptions for remaining SIDS should be based on pre-existing trade agreements and on income level, historical GHG emissions, and their climate vulnerability.

Finally, the EU should leverage existing funds to disburse the revenues raised from the sale of CBAM certificates. To do so, the Commission should use the fund of the European Green Deal (EGD) to provide climate financing to LDCs and SIDS that is at least equivalent to the amount of revenues generated, deducting the administrative costs of CBAM (Perdana & Vielle, 2022). That would align with the Parliament’s initial intent to originate climate finance through the proceeds of the CBAM (Oxfam International, 2022). The Commission could also leverage this as an incentive mechanism, whereby investment reporting in decarbonization efforts should be conditional for exemptions. Naturally, CBAM-affected sectors should be prioritized.

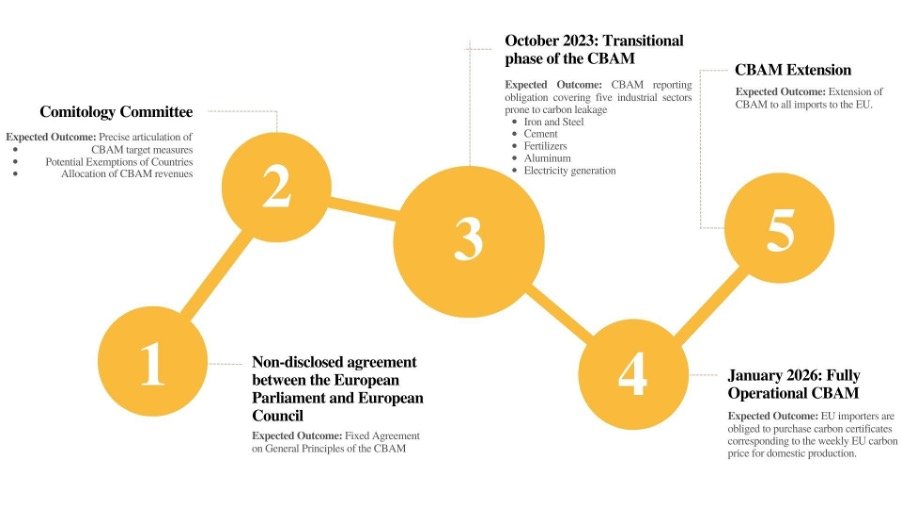

Figure 5. Authors’ elaboration based on the timeline provided by the EU Commission

Altogether, the introduction of exemptions, increased financing, and improved dialogue will contribute to designing an equitable CBAM that acknowledges varying levels of development. Moreover, a well-designed CBAM can alleviate the increased risks of carbon leakage and the disincentivization of transitioning to a low-carbon industry.

In doing so, the CBAM can effectively comply with international principles of climate mitigation, as well as with the EU’s own development agenda. Implementing an equitable CBAM will equip the EU with the necessary diplomatic and political capital to accelerate mitigation efforts, placing it at the forefront of the fight against climate change.

This policy brief was presented at the 4th edition of the FuturEU competition, sponsored by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and the CIVICA alliance. Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Primary sources

Bosetti, Valentina. (2023, February 14). Expert interview on policy options for the CBAM. [Personal Interview].

Hornidge, Anna-Katharina. (2023, February 7). Europe: (Which) Growth Wanted?, ISPI, Milan, Italy. [Open event contribution].

Taschini, Luca. (2023, February 20). Expert interview on policy options for the CBAM. [Personal Interview].

Secondary Sources

Ameli, N., Dessens, O., Winning, M., Cronin, J., Chenet, H., Drummond, P., Calzadilla, A., Anandarajah, G., & Grubb, M. (2021). Higher cost of finance exacerbates a climate investment trap in developing economies. Nature Communications, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24305-3

Eckstein, D., Künzel, V., Schäfer, L. (2021). Global Climate Risk Index 2021. Who Suffers most from Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2019 and 2000 - 2019. Germanwatch. https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/Global%20Climate%20Risk%20Index%202021_2.pdf

Eicke, L., Weko, S., Apergi, M., & Marian, A. (2021). Pulling up the carbon ladder? Decarbonization, dependence, and third-country risks from the European carbon border adjustment mechanism. Energy Research &Amp; Social Science, 80, 102240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102240

Gore, T., Blot, E., Voituriez, T., Kelly, L., Cosbey, A., Keane, J. (2021). What Can Least Developed Countries and Other Climate Vulnerable Countries Expect from The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)? European Environmental Policy (IEEP), Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI), International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), Overseas Development Institute (ODI). https://ieep.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/What-can-climate-vulnerable-countries-expect-from-the-EU-CBAM-IEEP-et-al-briefing-002.pdf

Lowe, S. (2021). The EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism. How to make it work for developing countries. Centre for European Reform. Open Society European Policy Institute. https://www.cer.eu/publications/archive/policy-brief/2021/eus-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-how-make-it-work

Our World in Data. (2023). Share of global cumulative CO2 emissions. Our World in Data. Retrieved February 23, 2023, from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-of-cumulative-co2?time=1990..2020

Perdana, S., & Vielle, M. (2022). Making the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism acceptable and climate friendly for least developed countries. Energy Policy, 170, 113245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.113245

Tenwick, J., & Richart, P. (2022). European Parliament vote on carbon border tariff is a step up but still unfair to poorer countries. Oxfam International. https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/european-parliament-vote-carbon-border-tariff-step-still-unfair-poorer-countries

UNCTAD. (2021). A European Union Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Implications for developing countries. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD/OSG/INF/2021/2. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/osginf2021d2_en.pdf

UNDP. (2023). The State of Climate Ambition: Snapshots for Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) | United Nations Development Programme. (n.d.). UNDP. https://www.undp.org/publications/state-climate-ambition-snapshots-least-developed-countries-ldcs-and-small-island-developing-states-sids

illuminem briefings

Carbon Regulations · Public Governance

illuminem briefings

Public Governance · Carbon Regulations

illuminem briefings

Carbon Market · Carbon

Euronews

Public Governance · Carbon

Carbon Herald

Carbon Market · Carbon Regulations

Politico

Carbon Regulations · Carbon Market