Why facts are not enough: understanding on what basis we make decisions can change our planet

· 10 min read

Every single day we make thousands of decisions. Even if it is unclear to us, they are based on expectations – what we think will happen – and values – what we want to see happen. This is no different in times of crisis, except such decisions have more complex, long-term, and potentially disastrous outcomes. Regarding climate urgency, understanding why decision-makers opt for certain choices is fundamental if we wish to steer society onto a more sustainable pathway.

If climate change and the biodiversity extinction crisis pose existential threats to our societies, how can we explain the lack of effective action by policymakers to curb the trends of environmental destruction? To answer this question, one has to turn to the thought processes involved in decision-making. When making conscious decisions about what needs to happen in the future, we necessarily use a mental model of the world – what we think will happen when we make this decision – but this mental model is partial, flawed, and systematically biased. Why is it that, when presented with scientific evidence, policymakers refuse to act accordingly? Why are powerful segments of society actively refuting facts? These apparently naïve questions deserve to be carefully explored if we are to move beyond the obvious, sometimes angry answers that first spring to mind. What drives those in power to make these decisions? How can we as individuals and societies consciously shape our future?

The field of rationality and decision-making is well established. However, Dr. Claude Garcia of Bern University of Applied Sciences and Dr. Patrick Waeber of ETH Zürich, Switzerland, have approached it from a different angle. Rather than trying to identify the factors that push someone to take a certain decision or revise it, they have contemplated all possible situations in which a decisionmaker can be when confronted with a tough choice. Through a series of four simple questions, they have managed to cover the entire range of situations. When facing a given topic, in order to respond efficiently, decision-makers must: 1) be aware of the topic, 2) understand its causes, 3) value its significance, and 4) have the means to respond effectively.

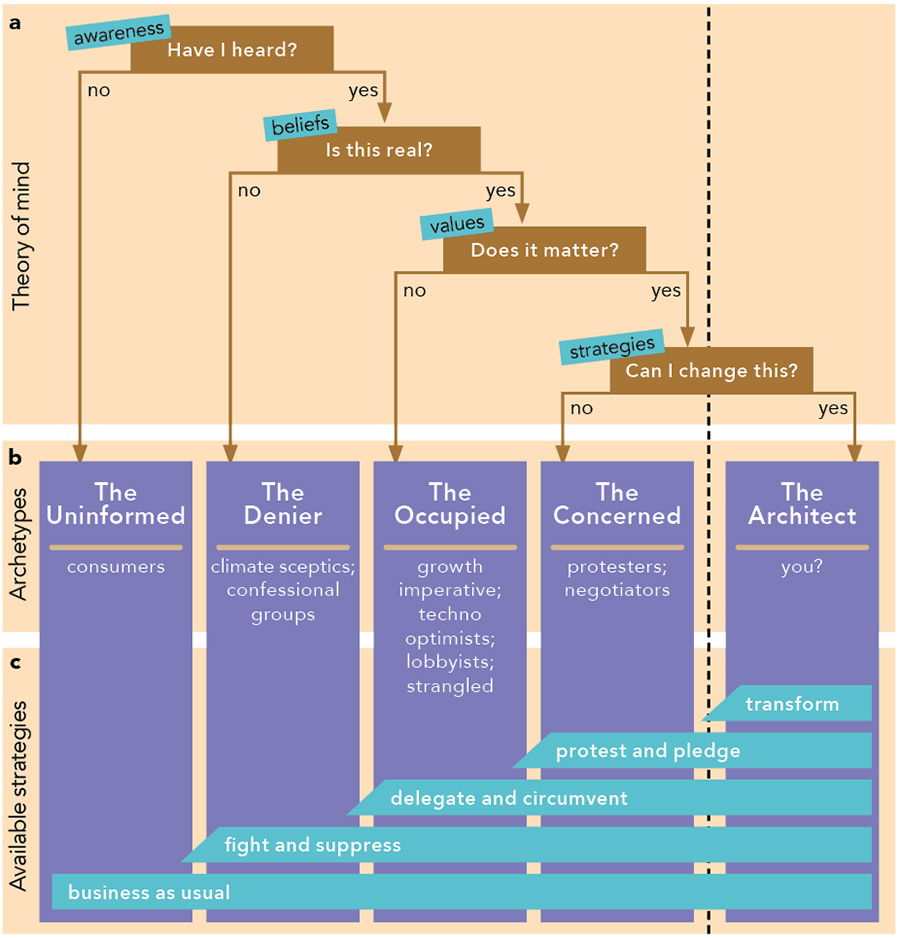

Figure 1. Choices we make: a) a framework to develop a theory of action; b) all archetypes operate rationally under their conditions (eg, social, educational); c) they strategise with different information at their disposal, and under different values, beliefs, and capabilities.

Source: Modified from Waeber et al (2021), doi.org/10.3390/su13063578 (adapted from Sylvain Mazas, 2021)

These conditions help the researchers identify five archetypes in total.

Each individual person navigates between these archetypes depending on the information, belief, values and means at their disposal at any given moment in time. We also have meta-agency over our archetype where we may deliberately present a false representation of our principles. One might consider greenwashing to fall here, an ‘Occupied’ masquerading as an ‘Architect’. Displaying animosity against environmental interests in order to conform or curry favour in certain spheres while secretly sharing the concern is also a possibility, at the cost of strong cognitive dissonance.

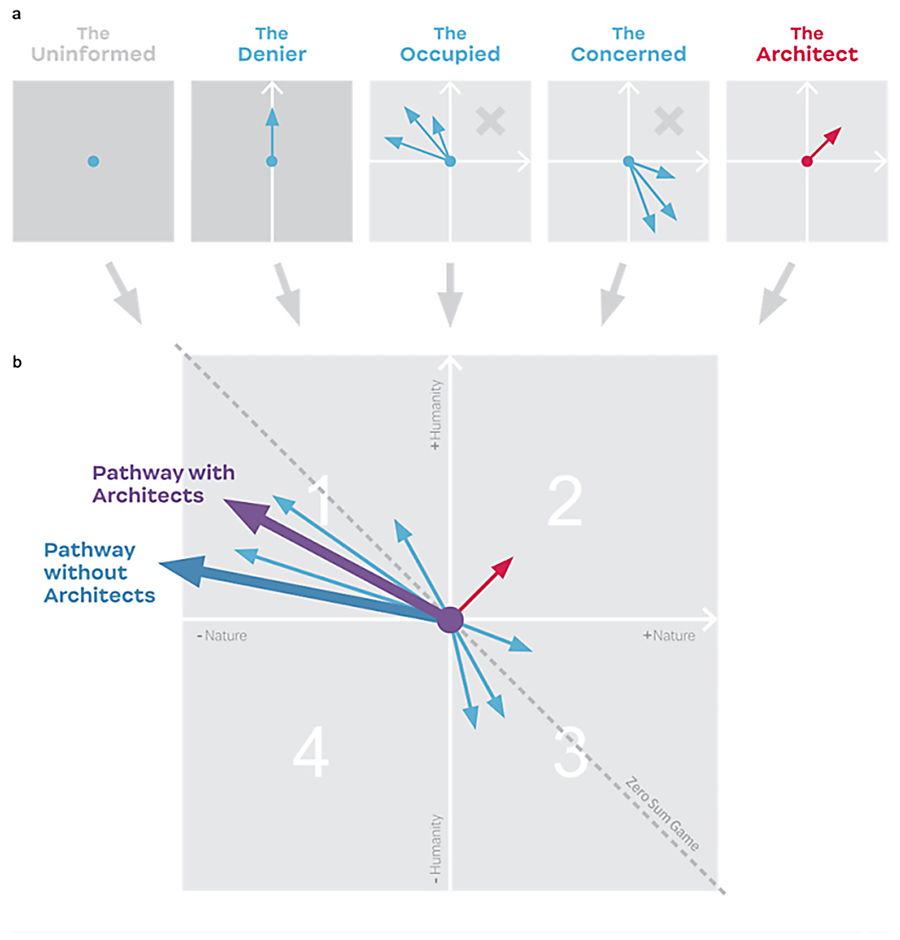

The world is not simple. There are a multitude of different concerns for citizens to consider, some environmental, many not. Garcia and Waeber envisage this as a multidimensional solution space through which the world moves. The many dimensions (axes) represent variables that the citizens take an interest in. For the sake of simplicity, Garcia and Waeber use ‘nature’ on the x-axis and ‘humanity’ on the y-axis, often represented as conflicting targets. These can be related to SDG (Sustainable Development Goal) 1 (Poverty) and SDG2 (Life on Land). The result is a space where we can see nuances, trade-offs, and synergies between these two goals, rather than just polarised wins and losses. This space acts similarly to a political compass. In addition, we can also visualise the impact of someone’s choices as a vector pushing the world in a given direction, with arrow length representing power.

”The Architect is the alternative to conflict.”

For example, a citizen acting as an ‘Occupied’ would actively pursue humanity’s welfare, pushing back the health of nature as a sad but necessary sacrifice, whereas a ‘Concerned’ citizen would be willing to undergo discomfort and embrace sobriety to leave space for nature. By definition, only the ‘Architects’ push towards win–win outcomes. Furthermore, we can combine archetype arrow length and weight to view aggregate trends, depending on the world’s current composition of archetypes.

Figure 2. The solution space is a framework to represent the development pathways each archetype is ready and willing to explore. There are four sub-spaces for exploration: 1) humans win at the expense of nature; 2) win–win pathways; 3) nature wins at the expense of humanity; and 4) all lose. Vectors are used to represent agents and their decisions: i) the length of the vector represents the power of an agent; ii) the direction reflects the intentions of an agent; iii) the angle (compared to an axis) denotes the efficiency an agent establishes for the trade-off between the two dimensions (axes).

Source: Modified from Waeber et al (2021), doi.org/10.3390/su13063578 (adapted from Sylvain Mazas, 2021)

These visualisations are useful as they can help us see how different issues (eg, SDGs) play off against one another in today’s context. However, the real question is: how do we shift those arrows towards the win–win quadrant of the solution space and foster the emergence of more ‘Architects’? We can do this by empowering people by providing them with information, beliefs that match existing causal links, an invitation to broaden the scope of their dimensions of interest, and a means with which to act.

Tropical forests and the issue of deforestation are good cases to test this framework. Deforestation is an ongoing process, contributing to the climate and biodiversity crisis. In 2018 alone, 12 million hectares of tropical forest were lost, an area the size of Belgium. As it stands, nearly all stakeholders involved in deforestation belong to the first three archetypes: ‘Uninformed’, ‘Denier’, or ‘Occupied’. Therefore, slowing, halting, and reversing deforestation will be a daunting task and can only be achieved against their collective will.

One of the possibilities is to adopt a confrontational stand – betting that the struggle will push the system away from its current lock-in. This is what ‘Concerned’ decision-makers could opt for. It requires considerable power to turn the tide against intelligent and determined opposition. The pathway Garcia and Waeber propose is to devise alternatives to the tug of war, betting on collective intelligence.

”It is possible to shape our future rather than just witness it.”

Differences over values are apparently crippling to the design of effective collaboration. However, irrespective of this, the framework highlights people will find it difficult or impossible to cooperate if they do not share the same beliefs. One of the most significant implications of the theory proposed by Garcia and Waeber is that it suggests a bypass to overcome divergence in values by focusing on building common beliefs on which to jointly design strategies.

Putting this theory to the test, though perhaps in a surprising way, Garcia and Waeber have applied this concept to design and broker agreements over forest landscape management in Central Africa. Stakeholders and institutions involved in managing intact forest landscapes were invited together to play strategy games. These games, designed and adapted through participatory research and modelling, condense the real-life situation as accurately and succinctly as possible. In each game session, players took on their own role or one of the other stakeholders engaged in the discussion. The games allowed in-person discussion and illustrated future problems in a setting where they could be understood, discussed, and worked through.

At the end of each game, stakeholders debriefed and analysed both their actions and the games themselves. This provided the researchers with feedback to refine and improve their models. More importantly, it provided the players with a shared set of beliefs about how the system works – the rules of the games they had just discovered. And since it was just a game, no harm could come and participants could explore freely the outcomes of their proposed actions. The games could fast forward landscape dynamics to peek into possible futures.

By gathering in these game and scenario exploration workshops, stakeholders were able to listen to each other’s lived experiences and understand. After playing the games, stakeholders were far more willing to revisit their initial beliefs in light of what they had experienced together. New compromises were easy to identify based on evidence, which was either new to them, countered their previous opinions, or became more pertinent. The participants were provided with information, a common set of beliefs, a better understanding of each other’s values, and could imagine together new forms of collaboration.

These models and games can be used anywhere – at the core of this framework is that it considers everyone equally, irrespective of gender, culture, affluence, or creed. It applies equally to urban elites in the Global North to pious pioneers in Central America and Indigenous communities in Sarawak. Given the power asymmetries, systemic ‘lock-in’, and technological means in the Global North, it seems potentially promising to try to shift the mindset of ‘Deniers’, ‘Occupied’ and ‘Concerned’ archetypes at this end of the scale.

There is a crucial point – the archetypes are tied to a specific question. A different question would reshuffle the deck and one cause’s ‘Architect’ could very well become another one’s ‘Denier’. The framework does not require the beliefs of the ‘Concerned’ ones to be actually true. In that sense, it is a general theory to predict the responses of humans, irrespective of their condition, when faced with a new situation. You can try it out yourself, and see how you navigate yourself between the different archetypes on the issue of COVID-19.

If we can understand how and why we make our decisions, it is possible to shape our future rather than just witness it. Mind, after all, is for anticipation.

This article was also published on Research Features. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

References

illuminem briefings

Social Responsibility · Sustainable Lifestyle

illuminem briefings

Sport · Social Responsibility

illuminem briefings

AI · Green Tech

Deutsche Welle

AI · Green Tech

The Independent

Effects · Climate Change

The Globalist

Climate Change · Effects