What will the planet bring to reduce carbon emissions (II/II)?

· 9 min read

This article is part two of a two-part series on the unintended negative consequences of fighting climate change. You can find part one here.

While computer models once predicted expanding deserts due to global warming, satellite imagery paints a different picture: a greener Earth. Yet, as efforts to reduce CO2 intensify, this 'global gardening' trend may reverse, potentially causing desertification in regions like Africa and affecting billions of lives. The debate over climate action demands a comprehensive understanding of these potential consequences.

Meanwhile, the main tool of modern Western climatology was computer modeling, which did not say that because of CO2 emissions and global warming, global gardening could begin. On the contrary, models often predicted the expansion of deserts on the planet.

The fact is that most models suggest the expansion of the so-called Hadley cells responsible for the appearance of arid zones in the tropics. Moisture evaporated over equatorial oceans, with warm and humid air masses, moving south and north, toward the poles. There, these masses are cooled and reduced, and moisture falls in the form of precipitation over Northern or subequatorial Africa. That is why, for example, there is almost no rain over the Sahara and extraordinarily little over the Sahel.

Modeling showed that the Hadley cell area should grow larger, the higher the temperature. True, this was contradicted by the lack of appropriate paleoclimatic data, in fact, in the warm periods, the Sahara and the Sahel were greener than in the cold. But for the time being, they simply did not pay attention to this.

All changed the satellite images. Thanks to them, it became apparent that the African Sahel is one of the most intensive landscaping zones on the planet. Then meteorological data also showed up, which showed an increase in precipitation over the Sahel. Nevertheless, these data have not yet become widely known, and former ideas prevail in society.

Thus, the United Nations Food Organization (FAO) systematically reports that the world’s forests are shrinking. However, the definition of the word “forest” used by this organization, on the one hand, includes areas where there are no trees at all (roads, glades, fire cuttings, etc.), and on the other hand, excludes areas overgrown with trees, if more than 10% of such areas are not covered with trees five meters high or more. At the same time, neither the biomass of trees nor their number in this area is a forest criterion for FAO.

In addition, the situation is complicated by the fact that FAO does not directly consider the forest area: instead, an estimate of the density of the forest in each land area is taken and multiplied by the total area of that area. With rapid changes in the actual coverage of the forest area, this method can produce certain errors.

Satellite imagery has its criteria: for them, clearances are not forests, but a significant part of the areas that are not forests for FAO may well be counted as forests. This causes systematic discrepancies between the theses of the UN on the loss of forests and the fact that they describe scientific papers based on images.

Satellite images show a much less sad picture: the net leaf area in the forests grows by about 100 thousand square kilometers (more than three-quarters of Greece’s area) per year. The earth is not deprived of forests and vegetation, but, on the contrary, is quickly covered by them. By the end of the century, forests will add about as much leaf area as the entire European continent.

However, this does not mean that existing forests can be cut down at the root: of course, the young forest, growing due to global anthropogenic gardening, gives a completely different ecosystem than the old one. Therefore, the reduction of the latter should still be kept under control.

But in general, the situation is such that because of the well-established expectations associated with the “desertification” of the planet due to the growth of Hadley cells, alternative opinions are simply not heard. According to the famous Sahara researcher Stefan Kraepelin, the empirical data turned out to be buried under a mass of works describing what is happening only within the framework of mathematical models.

“I have been studying the Sahara for 30 years and I can say that it is getting greener… Nomads graze their flocks where they could never have before… I tell everyone: come to the desert and see for yourself. But everyone is too busy with their computer models, and they don’t care what happens in practice.”

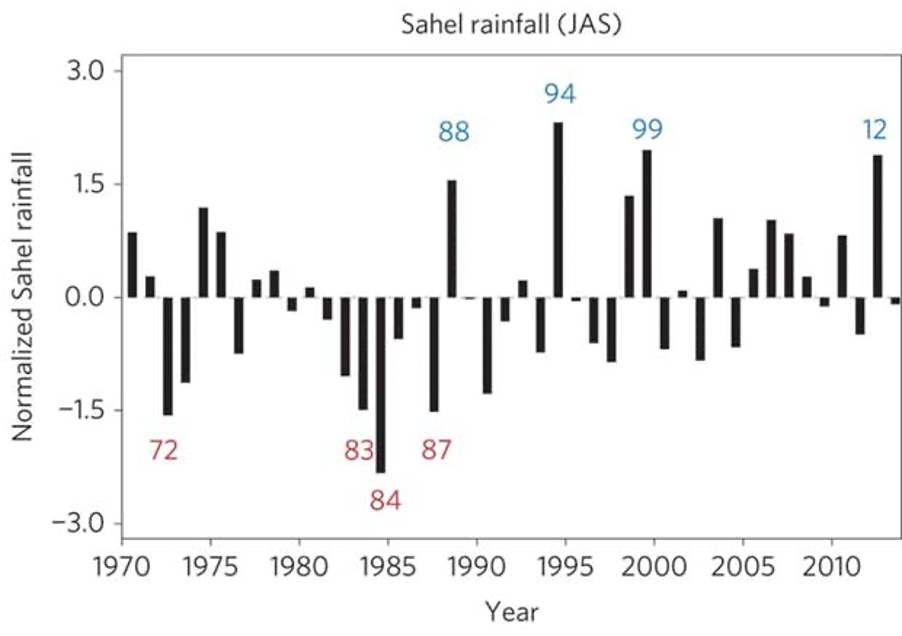

Figure 2. Rainfall levels in the Sahel from the 1970 to 2010

Normalized sediments in the Sahel show an upward trend.

Eventually, all good things end. The same is waiting for the greening of the planet. The fact is that the use of coal all over the world is declining, and this happens most quickly in China, which consumes half of the 8 billion tons of coal produced annually and produces half of the CO2 emissions from it (China accounts for 7 billion tons carbon dioxide emissions per year). If in the early 2010s, coal-fired power plants in China accounted for more than 80% of electricity generation, now it is less than 60%, and only in 2016, coal production in China fell by 9%.

Of course, CO2 is formed during the combustion of not only coal but also other types of fuel, such as methane. However, per unit of energy obtained by burning methane gives tens of percent less carbon dioxide (due to a different chemical composition). More importantly, the production of electricity in solar and wind power plants is growing faster than in gas power plants.

The Western world is aggressively developing CO2 injection technologies in underground storage facilities. There is another category of projects: geoengineering, “reworking the Earth”, providing, for example, the dispersion of sulfur dioxide in the stratosphere, which will lead to the cooling of the planet. As is known from the school course physics, the lower the temperature, the lower the evaporation, and therefore, the less precipitation.

Eventually, at least some of these projects will be implemented. As soon as anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide fall from the current 37 billion tons per year to at least 20 billion tons, a noticeable increase in the CO2 content in the atmosphere will almost stop. One of the scenarios of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — RCP 2.6 — provides for the reduction of such emissions already in the 2020s and overcoming this threshold no later than 2030.

This will first slow down the current greening of the planet and then turn it back on. At present, this situation looks hypothetical, but climate experts believe that without reducing greenhouse gas emissions, it’s likely that “there’s no way”. And if so, in the future, forest and steppe landscapes will not be able to keep where they penetrate today: they simply will not have enough water. Not only will there be less precipitation, but a decrease in the amount of carbon dioxide in the air will cause the plants to lose water faster, opening the stomata for CO2 extraction more widely. The planet will face the inevitable loss of vegetation.

On a planetary scale, the size of future desertification is difficult to estimate. To do this at least approximately, it is necessary to understand how far the greening of the planet can go.

The latest work on this topic reports that climate change in the African Sahel and the Arabian Peninsula will more than double the amount of precipitation there. This means that today’s semi-deserts and deserts of these regions, with a total area of more than six million square kilometers, will turn into savannas and light forests.

It is doubtful that the vegetation that grows there will be able to exist without water. And it is possible that after the end of anthropogenic CO2 emissions and the possible beginning of geoengineering, desertification will severely hit these areas.

In developed countries, people have almost nothing to worry about. Their population either does not grow or decreases. The reduction of land covered with vegetation will leave enough land for local people to grow food.

However, a decrease in agricultural yields (inevitable with falling atmospheric CO2) will force a person to either press down wildlife, expand arable land, or start using more pesticides and inorganic fertilizers.

More difficult will have the animal world of these countries. After the start of a decrease in CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, plant biomass will grow much more slowly than it is now, at the same pace as in the era before the Industrial Revolution. Hence, the amount of plant food for the animal world will drop by tens of percent.

It may seem that there is nothing to worry about and less developed countries: half of Africa and almost all of Arabia in the historical epoch were not spoiled by an abundance of vegetation, so there is nothing for them to lose. But it only seems. The Sahel and the whole of Africa are characterized by rapid demographic growth and forecasts predict that the population will be 3.7 billion by 2100.

If gardening comes to the desert, everything will be fine. An increase in the CO2 content in the air increases yields in today’s fields lying outside the desert and semi-desert zones. If we exclude the scenario of the most radical geoengineering, landscaping will last more than a hundred years. During this time, Africans are likely to inhabit at least part of the former deserts and semi-deserts. The agriculture of these areas is adapting to the growing amount of precipitation and increased CO2 content in the air — and the arable land area and yield will also go up.

But in the case of the success of projects on pumping out CO2 from the air and active geoengineering, all these processes can be reversed. Yields will decrease, and the former fields will become desert and semi-desert. Hundreds of millions of people will face the prospect of mass starvation.

I repeat, all this is no more than theoretical calculations. But they should at least be considered when developing today’s plans to combat global warming.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Gokul Shekar

Effects · Climate Change

Simon Heppner

Effects · Climate Change

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Effects

El Pais

Effects · Climate Change

Euronews

Labor Rights · Climate Change

Yale Climate Connections

Effects · Climate Change