We’re thinking about climate risk the wrong way

· 11 min read

There’s a huge difference between asking “what’s most likely to happen, and how could that affect us” versus “what’s the worst that could happen, and how likely is that.” While the latter is the traditional risk management framing, the first approach is how most Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports are presented, at least at the summary level that is consumed by senior policy- and decision-makers.

No wonder then, that many people still see physical climate risks as gradual, with extremes worsening incrementally and linearly. And why most climate risk assessments seem to make the same assumptions.

There are two problems with this. The first is that we’re already seeing abrupt and discontinuous changes, such as the unexpected and persistent material upward shift in average ocean temperatures in mid-2023, which has now seen every day for over a year at unprecedented levels.

The second is that physical risks often have natural break points given differing vulnerabilities, where damage suddenly tips from being negligible or manageable, to significant or catastrophic. For example, residents of the Australian city of Lismore discovered this when they suffered unprecedented flooding in 2022. While many had experienced previous inundation of the lower level of their properties, this event drowned entire buildings. People who had stored their belongings on an upper level, expecting them to be safe, were left devastated.

In fact, as the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries put it in their recent paper Climate Scorpion, “the sting is in the tail risks”: the unlikely but high impact events occurring in the tails of a probability distribution. Climate change is shifting extreme weather distributions to the right and, at least in the case of temperature extremes, is flattening the bell curve, with longer and fatter tails. What were once highly unlikely events but within the distribution curve are now more likely; and what were once inconceivable are now possible.

Most climate projections are still modeled at a fairly coarse range due to the massive computing power required – in the best cases squares that are perhaps 10km by 10km (many are around 100 km by 100km). They are good at establishing regional trends in certain weather conditions over multi-decadal periods (such as average temperature and seasonal precipitation trends) but are less useful for projecting localised phenomena such as flash flooding, large hail or extreme wind. Traditional design risk assessments based on historical “one-in-100-year” events are ill suited to a rapidly changing climate.

Further, so-called “positive feedbacks” (sometimes colloquially referred to as “tipping points”) that amplify or accelerate global heating, are not incorporated into many models. With mounting evidence that several of these feedback mechanisms may already have been activated, it is increasingly likely that climate projections are understated. The climate system appears to be more sensitive to changes in greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations than had been projected.

Speaking of which, just because many scientific papers generally end their projections by the year 2100 doesn’t mean that climate impacts level off at that point. In particular, ice is expected to continue melting for centuries, with multi-metre sea level rise already locked in. Only the rate of rise and long-term maximum sea level reached are dependent on our collective actions to mitigate emissions. In many areas, the question is not “if”, but “when” we are likely to reach devastating levels for a particular low-lying coastal city or region.

The bottom line is that climatic changes are likely to be discontinuous; impacts will vary widely depending on local phenomena and vulnerabilities; and the rate of change is likely to accelerate, as James Hansen and other climate scientists have warned.

The next limitation is that many risk assessments only consider first order climate risks. It’s typical to see physical climate risk assessments that consider direct local impacts such as flooding or coastal inundation, droughts, heatwaves, and severe storms affecting a particular facility. Some consider second order impacts such as delays shipping goods if roads around a factory are cut off by flooding or storm damage.

But what we’re starting to see are cascading and third order impacts. Towns devastated by the same or different climate disasters within months of each other, leading to structural changes in communities, or the availability of labour, insurance coverage, and capital. Unforeseen impacts to the accessibility or cost of inputs produced on the far side of the world that might render whole product lines uncompetitive or unviable.

Or how about the simultaneous failure of harvests in multiple breadbasket regions due to catastrophic shifts in growing conditions and/or collapse in pollinator populations, in turn leading to a massive spike in global food prices and widespread famine? While wealthy countries might be able to ride it out with government food aid or subsidies, it would likely ripple into massive population displacement including forced migrations and regional instability, at a scale we have never seen before. How could tens or hundreds of millions of climate or economic refugees at the borders of countries your business has operations in – or sells to – translate to risk, including rising protectionist policies? Meanwhile, companies providing discretionary items may be hit hard as consumer focus switches to essentials.

There are a couple of other factors related to physical climate risks that are poorly understood:

First is that the current rate of global heating is unprecedented. While the asteroid impact that condemned the dinosaurs to extinction was particularly sudden, that was a cooling event. The earth has never heated this fast. There is no time for most natural systems to keep up with the changes, especially given the almost fanciful “overshoot” emissions mitigation pathways, which assume a hotter level of warming can be reached before as yet unproven and unscaled technologies are miraculously deployed to reduce atmospheric GHGs and turn down the heat.

Secondly, if people other than climate scientists give this any thought at all, they may blithely assume that peak warming coincides with peak global emissions, and that the temperature will start to decrease as per annum emissions reduce. Unfortunately, while we keep adding emissions, GHG concentrations in the atmosphere keep rising.

The last decade is the coolest we will experience, at least until we reach “net zero” emissions (in a way that is actually consistent with atmospheric chemistry and the laws of physics, rather than what it says on somebody’s spreadsheet). And that’s in the increasingly unlikely event we haven’t triggered multiple positive feedbacks by then. If we have, the heating will continue, with nothing humanity can do to stop it short of radical and highly risky geoengineering projects.

This is because most types of GHG (including carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and dozens of industrial chemicals) are long lived in the atmosphere – taking hundreds to thousands of years to break down, and continuing their warming trick that whole time.

In fact, the carbon dioxide released by burning a tonne of coal traps heat in the atmosphere equivalent to around 70 times the energy released combusting the coal itself![1] Only methane breaks down in what might be considered human timescales.

Given the incrementalism assumed in many climate risk assessments, one seldom sees the sort of war gaming of seemingly extreme scenarios, but it is precisely these sorts of long tail risks that could be the downfall of many companies and governments.

And while companies should be vigilant to the tipping points of climate system feedbacks, it might be social tipping points that lead to their undoing. For example, it is increasingly observed that gratuitous consumption in the Global North, exemplified by the billionaire class with their private jets, yachts and profligate lifestyles, are responsible for a vastly disproportionate level of emissions and broader environmental harm.

Just as the inequalities of the uber-wealthy precipitated the French Revolution, it might not take much more to prompt widespread consumer boycotts and/or political backlash against brands and companies that, in and of themselves seem to have little climate risk, but are tainted by their association with big polluters.

Which brings us from physical risks towards transition risks. Here we have a classic case of tragically misaligned incentives, because the transition risks that stand out for many corporations tend to stand in opposition to the things we need to do to give our civilisation a fighting chance of surviving this century (and possibly even the next few decades).

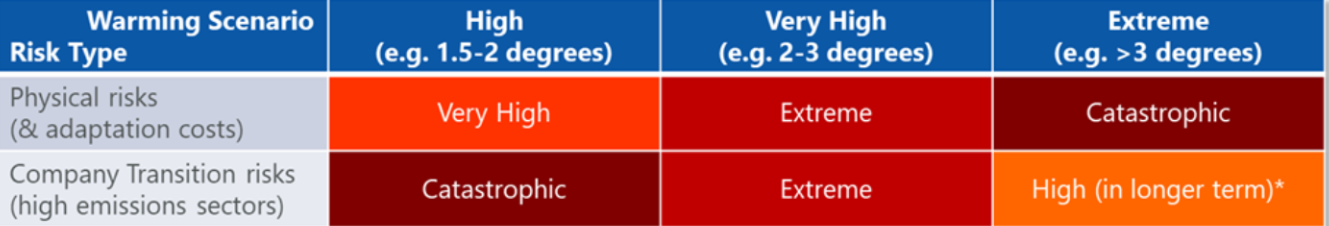

This is highlighted in the matrix below, showing that if governments were to start treating climate as the existential crisis that it is, transition risks would suddenly become catastrophic for whole industries, particularly those involved in extractive energy and emissions intensive products and services.

*In the high warming scenario, it is possible that policies enacting an emergency level, rapid transition would commence only once significant warming is “baked in.”

No wonder such companies and their industry groups are resisting change, resorting initially to outright denial of climate science, and more recently, since it has become obvious that the climate is changing, to ever more desperate efforts to delay the introduction of policies and measures that would effectively reduce climate pollution. It is now routine for big polluters to own the political discourse, through generous (though, in the scheme of things, trivial) donations; a network of aligned “think tanks” and media influencing policy and public discourse; and a veritable revolving door of lobbyists, advisors and politicians shuffling between industry and parliaments.

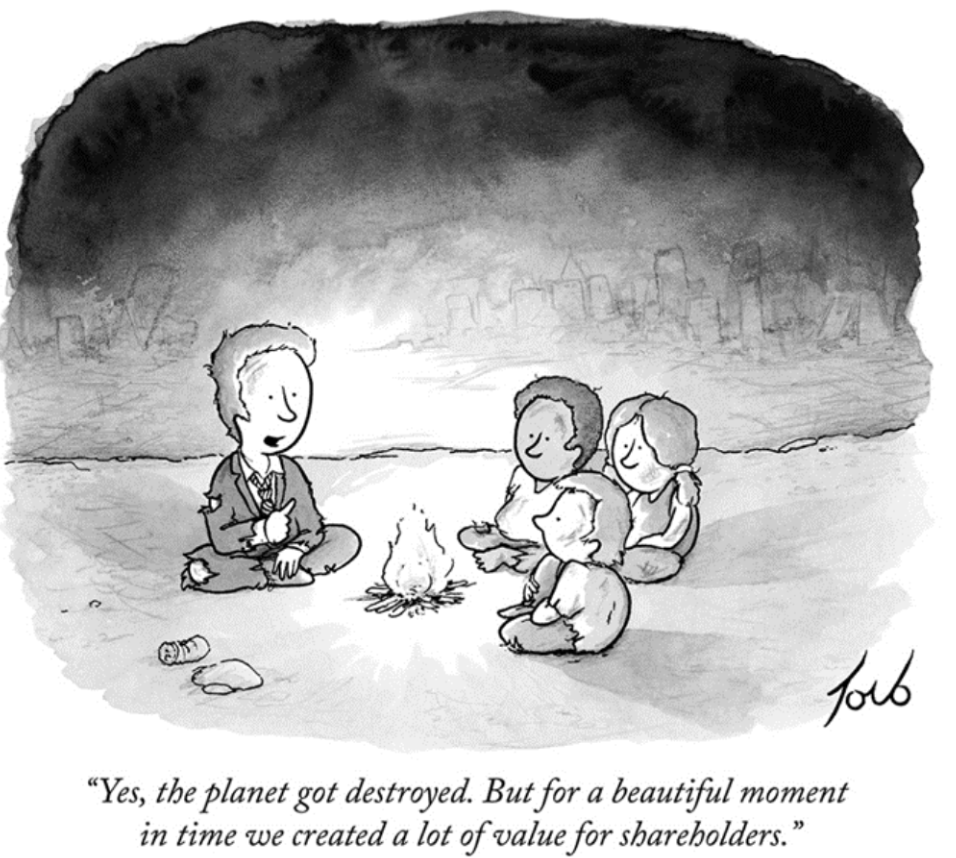

Decades of neoliberalism has put short term shareholder value maximisation at the centre of corporate actions. [2] The central financial concept of the time value of money (a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow), rationalises corporate actions that ignore the fact that there will be no business on a dead planet (as immortalised in a viral 2012 cartoon from The New Yorker).

Runaway climate change driven by positive feedbacks would devastate the biosystems we depend on (which are already weakened by over exploitation) and take our civilisation down with it. Having just experienced our first 12 month period with average global temperatures 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial times, there is no time to waste. There are clear limits to adaptation, particularly when it comes to preservation of biodiversity, agricultural systems necessary to feed an expected 10-11 billion people by mid century, and the longer term viability of low lying coastal communities and infrastructure.

Without signs of a rapid, radical rethink of our economic system, [3] which would need to be adopted in some form by all the major economies, it feels like we are in a death spiral. Sure, there have been encouraging shifts in sentiment and economics around the reduction of energy system emissions, but most governments are still moving at a glacial pace versus what is required, hamstrung by the donations and lobbying power of big polluters.

Globally, emissions continue to rise. The concentration of atmospheric greenhouse gases – the only climate indicator that really matters – continues to rise. Some of the world’s best climate scientists have moved from issuing ever more strident warnings, to non-violent direct action and uncharacteristic displays of anguish and grief, so devastated are they at the world’s failure to heed their multi-decadal warnings; so terrified are they, given their foresight about what is to come.

With mandatory climate disclosures however, investors, experts, advocacy groups and the public could have opportunities to take companies to task over the inadequacy of their emissions reduction efforts and their articulation of climate risks.

In the first instance, ensuring disclosure requirements are comprehensive, comparable, regimented and robust is critical. Risk assessments should be informed by a range of scenarios, developed by experts, that explicitly require discontinuous and long tail risks to be evaluated. Guidance should be provided to ensure complex and cascading multi-order risks are investigated. Unfortunately, the recent watering down of the US SEC’s proposed measures is another sign that our collective safety continues to be sidelined by people who do not understand – or care – about the risks.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

[1] Extrapolated from sources including Matthews, Gillett, et al, The proportionality of global warming to cumulative carbon emissions and Campbell, What harm could one coal mine do? Plenty – 1.7 million Hiroshima bombs of heat for starters.

[2] Jamies Montier, while at investment firm GMO, perfectly captured the perils of shareholder primacy in his whitepaper “The World’s Dumbest Idea.”

[3] It is beyond the scope of this article to propose what a sustainable economy might look like. Suffice to say, “green growth” paradigms that assume economic growth can be maintained but decoupled from emissions and other environmental harm seem naïve. Alternatives, such as degrowth (which, as an approach, often seems to be misunderstood by orthodox economists), feel more realistic in terms of where we need to get to as a society. The hard part would be initially persuading electorates to give it a try and, critically, stick with it through what might be a rocky implementation phase: this is the challenge of our democratic systems with their short cycles and shallow media coverage.

illuminem briefings

Biodiversity · Nature

John Leo Algo

Ethical Governance · Environmental Sustainability

Steven W. Pearce

Adaptation · Mitigation

The Washington Post

Biodiversity · Nature

Yale Climate Connections

Effects · Climate Change

Euractiv

Carbon Market · Public Governance