We’re heading for net-zero – what does it mean for buildings?

· 6 min read

“Greenhouse gases” (GHGs) include carbon dioxide, methane (the principal component in natural gas), nitrous oxides and a number of other compounds. They are mainly produced through the use of fossil fuels, and the production of steel and cement alone is responsible for over 10% of total emissions. In the atmosphere, GHGs act like a heat trapping blanket.

When a building is constructed there are “embodied emissions” associated with the extraction and manufacture of the materials, their transport, and the actual construction process (e.g. use of diesel and other energy on-site; construction waste; etc.).

“Operational emissions” include:

There are also end of life emissions associated with demolition and disposal.

So, what’s “net-zero emissions”? Basically, it means that a given activity produces no GHGs, or if it does, then those emissions are “offset” by activities that remove or avoid emissions elsewhere.

Why pursue a net-zero path? Apart from trying to maintain a more certain future climate, the answer is to avoid asset obsolescence. Increasingly, new buildings are being built to be net-zero by default. More occupiers are demanding buildings that can display better sustainability credentials and enjoy lower energy bills. Based on the empirical evidence when Greenstar was introduced, net-zero buildings are likely to be quicker to lease.

For existing buildings, embodied emissions are largely irrelevant – the building’s there, and, as is said, the most sustainable building is the one you don’t have to build. So how can we get operational emissions down to zero, as cost effectively as possible, and ideally way before 2050?

Like any goal, net-zero involves defining the problem with the current state, the desired future state and performing a ‘gap analysis’ to identify how to bridge the two. The gap analysis output then needs to be translated into projects that can deliver the desired future state.

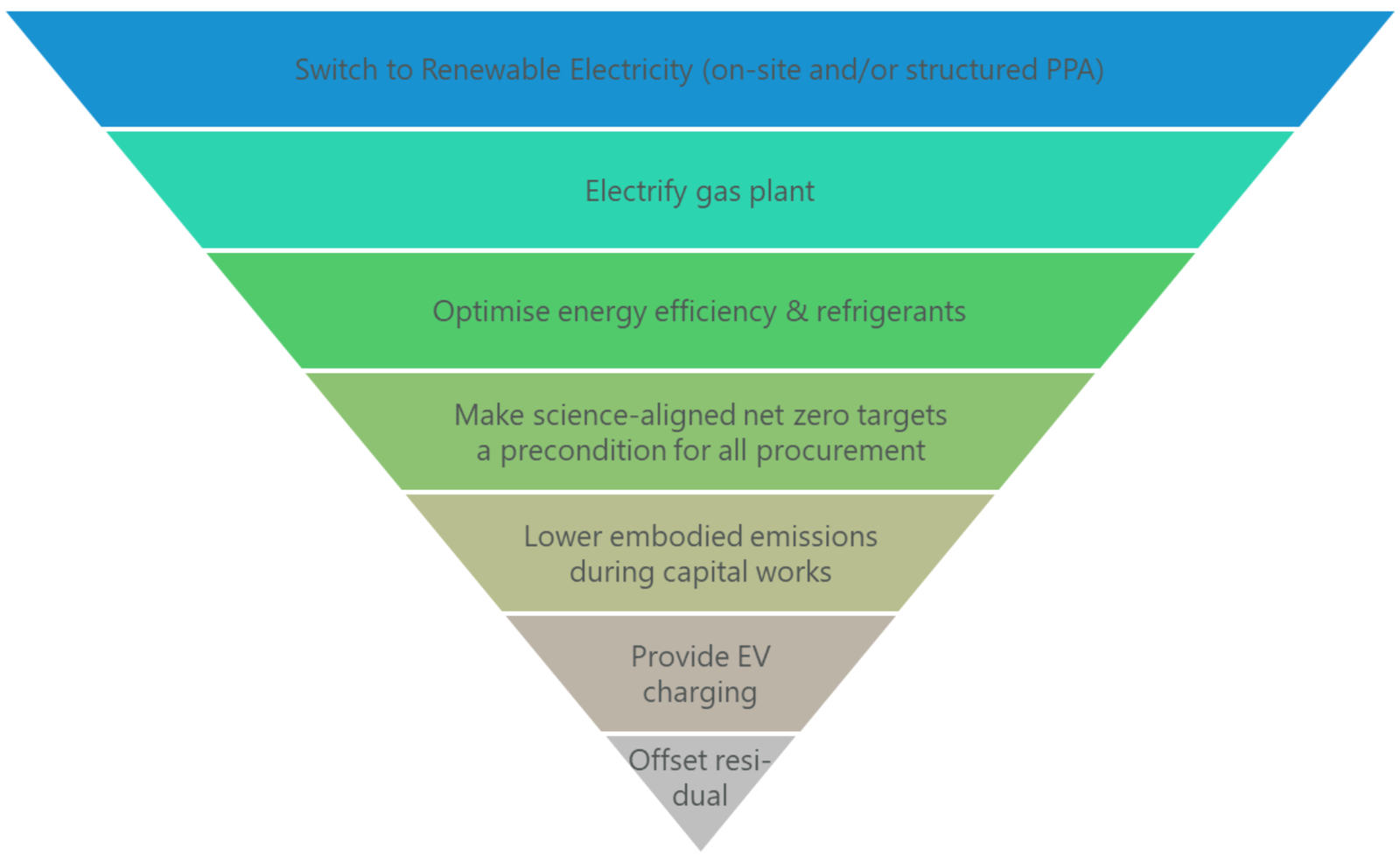

Our net-zero pyramid captures the steps, in approximately descending order of emissions reduction and/or future proofing benefit. It’s critical to assess this as an overall strategic package of works, because the various steps are highly inter-dependent. There are also additional benefits of tackling net-zero at a portfolio level.

Let’s break it down. Electricity forms the largest chunk of operational emissions for a commercial building, so sourcing renewably generated electricity is a logical first step. This might involve a combination of options, potentially involving on-site solar and battery storage.

A decade ago, the only way to source renewables was by paying a premium for accredited Green Power. With renewable generators now able to undercut coal and gas plants, arranging to purchase directly from a specific wind or solar farms may make sound commercial sense (aggregating usage over the course of 12 months, regardless of whether the renewables happen to be generating at all times your building needs the power – the actual electrons still come from the normal grid).

Generating on-site – behind the meter – delivers electricity with zero marginal cost and no network charges. Adding a battery facilitates not only time shifting (use excess generation in the middle of the day at other times), but also peak demand shaving opportunities – more on that in a moment.

Before rushing into a multi-year renewable power purchase agreement, it’s critical to model the electricity utilisation curve (intra-day, weekly, and seasonal) as you implement additional steps in the pyramid.

Gas is a significant source of emissions, and a building can’t achieve net-zero without electrifying existing gas plant: typically heating, hot water and cooking. That will change your electricity usage.

Electrification also generates a substantial energy efficiency dividend: heat pump technology is far more efficient than burning gas to make heat. And there are usually a range of other efficiency opportunities: not just with building services plant, but improving glazing and insulation, for example.

Of course, some of these initiatives involve significant Capex spend, so it’s important to align them with planned plant replacement cycles to optimise budgeted spend wherever possible. All of this goes into the energy modelling, including changes in maximum demand charges.

A less well-known source of building emissions are refrigerant gases. The Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol has resulted in a phase out of common refrigerants that are potent greenhouse gases. When planning electrification and other plant replacement, low GWP refrigerants (including natural refrigerants) should be used.

Where buildings have on-site car parking, the pyramid also identifies the need to consider electric vehicle charging. “Always Be Charging” is the ABC of EV ownership. Daytime charging can optimise utilisation of cheap on-site solar power, while providing a new revenue stream. Unless provided by a third-party operator with a separate utility connection, however, the provision of charging facilities will change overall power utilisation and peak demand, which needs to be considered in the model.

Clearly, developing a strategic net-zero roadmap is critical to avoid abortive spend, particularly when relevant plant fails ahead of planned replacement. Figure two highlights the components of a good roadmap.

As maintenance and other contracts come up for renewal, procurement processes offer a great opportunity to encourage suppliers to be doing their share of emissions reduction. One way is to ask potential vendors to demonstrate compliance with the Science Based Targets Initiative, with an emissions trajectory aligned with the 1.5oC goal of the Paris Climate Agreement. There are several net-zero certification schemes out there and some are of less worth than others, so it pays to ensure that suppliers’ claims have substance.

The same applies when procuring capital upgrade works, which provides an opportunity to significantly reduce associated embodied emissions if design, procurement and contractual documentation is suitably aligned.

On the other hand, in the absence of regulated net-zero emissions standards it’s important to set a boundary for emissions measurement in common with peer buildings, to avoid imposing additional costs on occupiers that won’t necessarily create competitive advantage.

The final step in the pyramid is to offset remaining emissions. As electrification and other initiatives are implemented, residual emissions will decrease. On the other hand, supplies such as water, waste and sewage all carry an operational emissions payload. Even when you complete the journey, all energy should be from renewable electricity, but there will still be some emissions associated with servicing. It’s beyond the scope of this article to cover the carbon offset market, other than to say it’s a minefield of often dubious claims.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Labor Rights · Climate Change

illuminem briefings

Architecture · Carbon Capture & Storage

Barnabé Colin

Biodiversity · Nature

Euronews

Degrowth · Public Governance

Politico

Public Governance · Climate Change

Mongabay

Climate Change · Environmental Rights