We need synergies, not silos, to solve humanity's greatest challenges

· 6 min read

Climate change is often framed as humanity’s greatest challenge. And for good reason. Every fraction of a degree of warming – the planet is currently about 1.2°C (2.2°F) warmer than before the Industrial Revolution – leads to more heatwaves, wildfires, and other extreme and erratic unnatural disasters. Moreover, stopping climate change requires more than just tinkering with one aspect of society; it demands a total reimagining of how our world operates across sectors and geographies.

But climate change is neither the only major challenge we face nor the one that’s a top priority for many people. Biodiversity loss is accelerating around the planet, jeopardizing countless ecosystems and species and, with them, the health and livelihoods of billions of people. Meanwhile, hundreds of millions of people worldwide still go hungry and live without access to electricity or clean drinking water.

This isn’t to suggest that there hasn’t been progress. Over the last several decades, international and multilateral efforts have lifted people from poverty, decreased levels of hunger, increased protected areas for nature, and decreased greenhouse gas emissions in many major economies. But the pace is not fast enough, and the scale is insufficient. Why? Because we continue to treat climate change, biodiversity loss, and human well-being as separate, unrelated crises. Only by working at the nexus of these challenges can we achieve meaningful progress toward a just, sustainable future.

Despite the interconnected nature of these challenges, we have continued to address them in silos with separate policies, institutions, and frameworks designed to tackle each one individually. But thinking, planning, and acting in silos has gotten us where we are today.

At a global level, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are the lodestars on climate, biodiversity, and human development, respectively. Distinct bodies or frameworks are not inherently wrong. But if they fail to work together or complement one another, they’ll also fail at meeting their own self-stated goals.

At national and sub-national levels, there are separate agencies or departments for energy, environment, social development, and other domains that rarely collaborate in ways that reflect their interconnectedness. Conflicting mandates are more common than not. At best, this is an inefficient way to solve social, climate, and environmental challenges, one that needlessly requires additional resources, time, and capital. At worst, it results in unintended consequences that slow down or negate progress on one or multiple challenges.

Recovery from unnatural disasters highlights the perils of thinking and acting in silos. There is often a push to build back quickly and similarly to how it was before. Of course, in some ways, that makes sense. What was lost was more than shelter. Building back can be a form of community solidarity. But by focusing solely on human well-being, we might create disaster relief policies and funding schemes that recreate the same risky conditions. The gains can – and given the growing intensity and frequency of floods, fires, and more due to climate change, likely will – be undone with the next major disaster.

Thinking outside of silos reveals new approaches. Building back better often requires building back differently, focusing on solutions at the nexus of people, nature, and climate. New infrastructure, building materials, and community design can be more energy efficient and better equipped to handle and evacuate from disasters. Floodplain forests soak up flood waters. Mangroves can decrease the power of storm surges and adapt to rising sea levels. Natural habitats on steep hillsides can prevent mudslides.

Moreover, these natural systems pull carbon dioxide from the air and store it in plants, animals, and soils. Concrete, metal, and earthen structures can reduce risks for people but have little benefit for nature or stopping climate change. They can even put communities at greater risk if the barriers fail and people have built up more in the high-risk areas. In contrast, solutions at the nexus of people, nature, and climate can help build short- and long-term resilience for communities.

Fortunately, as the crises themselves are inextricably linked, so, too, are the solutions. There are many solutions – real, practical, ready-to-go solutions – that synergistically mitigate climate change, improve people’s lives, and protect nature.

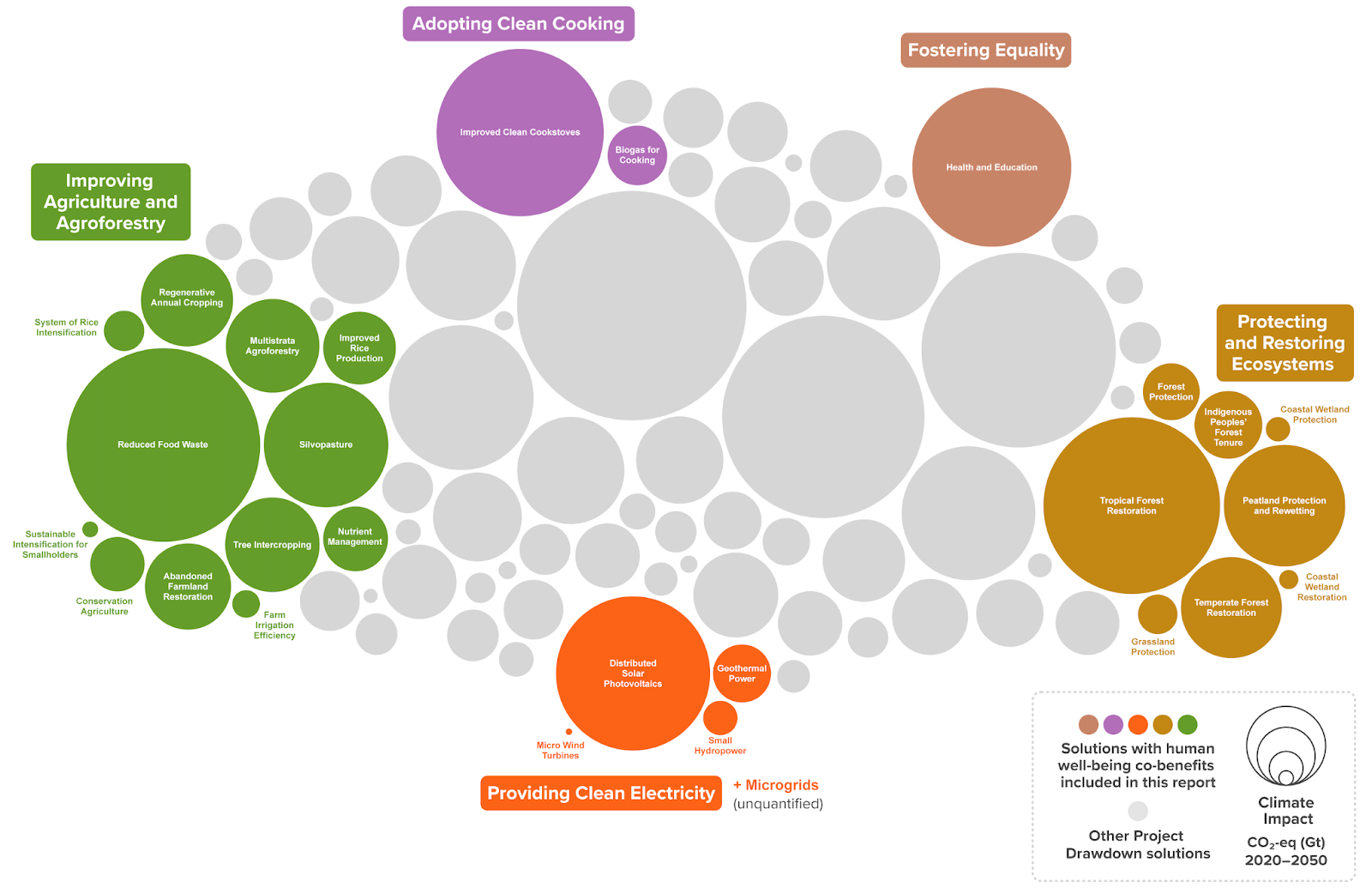

A few years ago, Project Drawdown began broadening its lens of how we view climate solutions to assess how (or if) they benefit people and nature. As a science-based organization, we started, as always, with the evidence. We reviewed hundreds of studies to determine how actions we think of as climate solutions can help lift people from poverty and food insecurity in rural communities in low- and middle-income countries. We found direct or indirect benefits to income, food security, health, access to electricity and clean water, and seven other dimensions of people’s well-being for 29 of the more than 80 climate solutions in our Solutions Library, several of which benefit nature, too.

Climate solutions provide many benefits for people in rural communities in low- and middle-income countries. See full report.

Many of these triple-win nexus solutions relate to how we grow and prepare food and conserve ecosystems. For example, clean cooking technologies can improve household air quality for the 2.1 billion people who still rely on cooking with highly polluting wood, charcoal, and dung. Poor air quality can lead to chronic illness and is a leading cause of premature deaths. Switching to cleaner fuels also frees up time spent gathering fuelwood, allowing more time for education and paid work.

But the benefits go well beyond improved air quality and more time. It also reduces tree harvesting, which degrades forests and increases greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, in a study across 35 countries, researchers observed a lower probability of diarrheal disease, a leading cause of childhood mortality, in people who lived downstream of healthy forests. This means that one solution – improving access to clean cooking – deployed in the right location can help mitigate climate change, improve air quality, increase education, raise incomes, protect forests, and decrease childhood mortality. Many other solutions also provide multiple benefits for climate, nature, and people.

More and more organizations and researchers are appreciating the benefits and tradeoffs between climate, nature, and people. Over the last 30 years, the number of studies on the so-called “co-benefits” of natural climate solutions has increased tenfold. At Project Drawdown, however, we have come to realize that there are no “co-benefits,” only benefits, and the most powerful solutions are those at the nexus, where investing resources and research results in improved outcomes well beyond what addressing climate, nature, or human well-being alone could achieve. In the coming year and beyond, we will be developing new tools and approaches to accelerate the world's understanding and adoption of these nexus solutions.

This article is also published on Project Drawdown. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Labor Rights · Climate Change

illuminem briefings

Architecture · Carbon Capture & Storage

Barnabé Colin

Biodiversity · Nature

Euronews

Degrowth · Public Governance

Politico

Public Governance · Climate Change

Mongabay

Climate Change · Environmental Rights