To decarbonize, focus on sectors rather than companies

· 8 min read

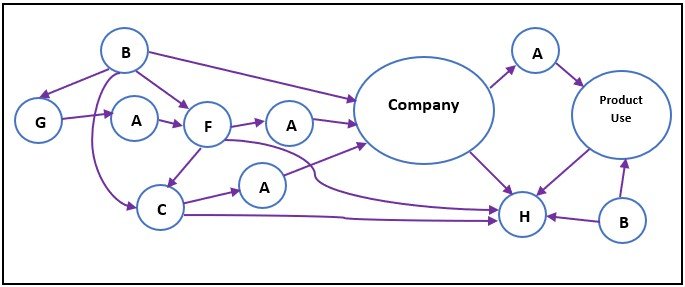

Corporate emissions accounting is implicitly based on a life-cycle perspective borrowed from product life-cycle assessment. The diagram below from the GHG Protocol’s value chain accounting standard illustrates how a single product’s life-cycle emissions make up a sliver of a company’s emissions across all scopes (ignoring for now that the company-level emissions inventory is for a year while the product-level inventory is not time-bound). This framework is great for attributing responsibility for emissions to the company that sits in the middle of the value chain and makes the final products that consumers use. But attribution doesn’t get us to decarbonization as we have argued previously.

The company-centric life-cycle perspective is ill-suited for decarbonization because so much of the emission reductions must happen outside of a company’s direct control. Focusing instead on key sectors in the economy can greatly reduce the complexity and simplify the decarbonization challenge. Climate policies and incentives are, in fact, increasingly aligned with a sector-centric approach.

It is well-known that scope 3 emissions from the value chain can easily account for 80-90% of the total emissions for companies that produce physical products, so corporate emission reductions often turn specifically into a scope 3 emission reduction problem. There are fundamental reasons why scope 3 reductions have bedeviled most companies to date:

Cutting scope 1 emissions would seem much simpler by comparison because companies have complete control over this, but reductions require electrification in most cases which in turn comes down to whether capital costs can be justified. If electrification of building heating, process heating, and company-owned transport can be undertaken then reductions in scope 1 emissions will be accompanied by increases in scope 2 emissions from electricity purchase.

Reducing scope 2 emissions brings its own set of difficulties. Purchasing unbundled renewable energy certificates (RECs) is the easiest approach, but will likely do nothing in reality because almost all of these RECs are non-additional. Power purchase agreements (PPAs) for renewable electricity are much more likely to produce additional emission reductions, but purchasers will need to be able to absorb the complexity and risks associated with PPAs. This rules out small and medium-sized companies from participating in renewable electricity unless they have access to aggregated PPAs. There is also a clear need for matching hourly electricity consumption with clean electricity production (known as 24x7 carbon-free electricity) which adds another dimension to the difficulty of cutting scope 2 emissions for real.

Instead of every company looking at upstream suppliers and downstream logistics to rope into decarbonization efforts independent of what other companies are doing, what if we focused on critical sectors that serve a large number of companies in the economy? Sectors, in other words, that many value chains must pass through in order for the economy to function.

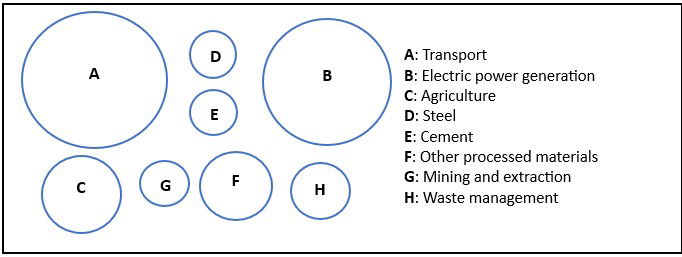

The diagram below illustrates a set of critical economic sectors, with the size of the circles roughly representing sector-level emissions. Even though there are economic transactions between sectors, sector-centric emission reductions would happen within each sector independent of its interactions with other sectors.

Compare this to the next diagram which illustrates just one company with a relatively simple value chain. In a company-centric approach, the company at the center of this value chain will not only need to account for its share of the emissions from all the sectors it uses (both upstream and downstream) but also somehow implement a decarbonization strategy that involves many of those sectors.

Now imagine millions of such companies, all trying to account for their value chain emissions (which mostly come from the same set of critical sectors) and looking to decarbonize on their own. The complexity and intractability of this undertaking would be off the charts. This is exactly where corporate emissions accounting and reduction targets are currently headed.

A sector-centric approach would funnel money and resources into specific sectors that generate most of the emissions in the economy, helping to develop common technologies and practices that could be used widely by all companies within those sectors and radically reducing the cost of decarbonization across the economy.

Using the US national emissions inventory as a guide, there are some obvious sectors at the center of the economy that should be (and increasingly are) the focal points for decarbonization:

When critical sectors like these get on a clear decarbonization trajectory with adequate funding and mandates, all companies and products using those sectors also decarbonize without additional effort. The sector-centric approach would fix the emissions problem where the emissions actually occur. Regardless of how we choose to attribute emissions, the only places where we can cut emissions are at the sources of those emissions.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Christopher Caldwell

Ethical Governance · Minorities

Gokul Shekar

Effects · Climate Change

Charlene Norman

Sustainable Business · Sustainable Finance

Responsible Investor

Sustainable Finance · ESG

Responsible Investor

Sustainable Finance · Corporate Governance

ESG News

Sustainable Finance · Corporate Governance