To achieve our climate targets it's time to revive the use of bans

· 6 min read

Under India’s G20 Presidency, in the beginning of March, Think20 (T20), which is an official Engagement Group of the G20, organized an event where I was asked to suggest recommendations in the field of climate smart policies. Looking at all the possible policy instruments and climate strategies to achieve the Paris Agreement targets and limit global warming, I decided to focus my intervention on one specific suggestion and that is to utilize more the use of bans in our mitigation efforts to reduce GHG emissions. Yes, those bans that were popular decades ago in environmental policies under what is known as "command-and-control". Such tools can set specific limits for pollution emissions, so the targets are fixed and known in advance.

Today, market-based instruments (MBIs) which focus on putting a price on externalities, such as taxes, charges, levies, tradable permit schemes, deposit refund systems and subsidies, have become the preferred choice in developed countries for environmental policy. This is because MBIs are considered more cost-effective than command-and-control approaches in addressing most environmental externalities. They give polluters the flexibility to respond to incentives by seeking the best sustainable technologies for reducing emissions. MBIs can also incentivize the market to reduce the pollution beyond the targets if possible.

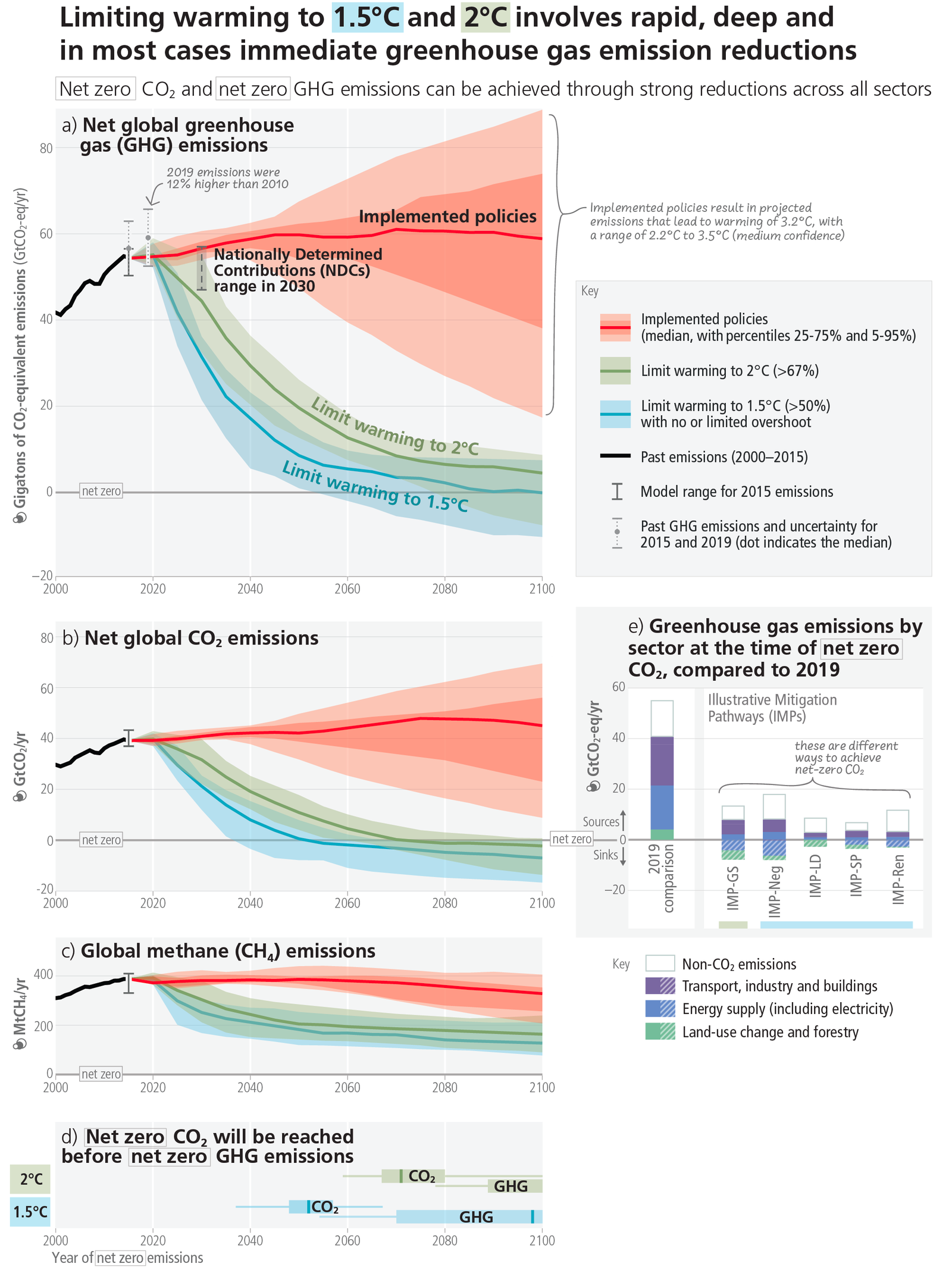

As an economist myself and having been the person promoting MBIs in the environmental policy of Israel, I believe MBIs should be at the core of environmental policies around the world. However, when looking at the climate scenarios we are headed towards, with the international community way behind in reaching almost every target, humanity is running out of time. The recent IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report states that the current mitigation policies and laws addressing mitigation "make it likely that warming will exceed 1.5°C during the 21st century and make it harder to limit warming below 2°C." Therefore, what is done today is not enough to close the mitigation gap. The report also states that "limiting human-caused global warming requires net zero CO2 emissions" and "the level of greenhouse gas emission reductions this decade largely determine whether warming can be limited to 1.5°C or 2°C."

In my view, MBIs, with the evolving and developing carbon markets are good and necessary but making them verifiably effective in actually reducing carbon emissions to the extent required will take years at best. This is time we don't have, as the report reveals.

This is why the use of bans is needed more where there are alternatives to polluting activities and products. I am not saying we need to ban the use of fossil fuels all together; it's not possible. However, as a strategy, bans should be considered much more along with the use of carbon pricing and other incentives, removing harmful subsidies, and promoting innovation and education. Bans should be a cornerstone of climate policies around the world.

There are many examples of the use of bans. In the past, when humanity recognized that the ozone layer was being depleted because of the use of certain chemicals, the international community moved quickly to ban ozone-depleting substances and mostly chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which were responsible for the deterioration of the ozone layer. When the direct adverse health effects caused by certain substances, such as with asbestos or polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were identified, countries were quite decisive in banning their use.

With global warming, as a tragedy of the commons, where most of the effects to date have been global or regional in scope, it is much harder to connect the cause and effect into coherent policy actions. Nevertheless, there are many examples of the growing use of bans. In the context of climate change and air pollution, India has decided to ban the use of diesel autorickshaws in and around New Delhi from 2027, with no new diesel auto-rickshaw registered in the National Capital Region (NCR) from the beginning of 2023. Some countries have also decided to end the sale of new petrol and diesel cars — the United Kingdom by 2030 and the European Union by 2035.

When speaking about bans, one should address the slight difference between the use of the terms "bans" and "phasing out" as most people today use the latter rather than the former. Bans shouldn't be abrupt; therefore, one can consider them as the "phasing out" of unwanted activities and products. Nevertheless, I find that there is a conceptual difference between the terms as bans suggest there is a clear and finite deadline while phasing out suggests the process is gradual, moderate and can be changed or modified over time. My suggestion would be to use the term "bans" as the default for such policy measures.

As with every policy, bans too should be adjusted to national circumstances as each country or sector has its own circumstances, alternatives, and options. A recent study, for instance, has found that the adoption of product carbon requirements (PCRs) which would establish near-zero-emission limits for basic materials would require that low-carbon production processes or substitute materials have reached a certain level of technological maturity which is not likely to happen before the 2030s. Nevertheless, there are sectors where it is possible to ban carbon-intense activities or products. If there is one area where it will be crucial to see change, it is in the use of coal and in this regard, many countries have already accepted the fact that technologically speaking, coal power plants can be permanently closed as cleaner technologies are readily available. In fact, at COP26 over 40 countries have pledged to phase out the use of coal power plants in the next decades, though the timeline is not consistent with the Paris Agreement.

It should be noted that when bans are not implemented properly, they may cause more harm than good. For instance, a study on the assessment of trucking bans in urban areas as a strategy to reduce air pollution found that banning the entrance of trucks during certain hours into the Medellin Metropolitan Area in Colombia did not significantly change the amount of pollutants (PM2.5). It was found that the emissions were more concentrated in the hours without restriction, causing a counterintuitive effect that could affect more human health.

A few last points on bans. Bans should also be accompanied by other measures to ensure the policy is just and fair, especially when the impacts of climate change and the policy changes do not equally affect the rich and poor, women and men, and older and younger generations or developed and developing countries. Bans are also not very useful in fostering innovation; therefore, governments should also combine them with other types of instruments as a policy mix which will eventually signal to everyone a clear direction. One other point addresses the IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report, which presented different opportunities for scaling up climate action. These included the need for switching fuels and reducing the emission of fluorinated gas. Such mitigation options and others should include bans where they are feasible.

Finally, to avoid reneging on climate commitments due to geopolitical events affecting the prices and sources of materials, energy products and destabilizing supply chains, governments along with the private sector should incorporate these scenarios and possible occurrences into their transition risk management strategies, allowing an orderly transition. This would limit the excuses of governments to delay or halt policy measures intended to remove completely the use of such far reaching and perhaps radical instruments such as bans.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Labor Rights · Climate Change

Steven W. Pearce

Adaptation · Mitigation

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

Politico

Public Governance · Climate Change

Mongabay

Climate Change · Environmental Rights

El Pais

Effects · Climate Change