This is why we should all be techne-optimists: an introduction (I/IV)

· 7 min read

We are techne-optimists.

But wait! Don’t throw that tomato.

We are not fans of the a-z Techno-Optimist Manifesto. Our unique flavor of ‘techne-optimism’ (something we will later describe, largely due to our value system, assessment of ‘the facts’, and our philosophy of technology, as something like the bio-psycho-social-cultural-economic-techne belief that things can get better, potentially much better, if we more deeply connect, authentically and inclusively collaborate, and effectively coordinate wise and responsible relational action… Fuck! We’ve just given it away) has been core to the living philosophy of Tethix prior to day 1.

The goal of this essay is to:

We expect this – a genuinely preferable future – will include (and of course, not be limited to) a wise, responsible and ecological relation to technology.

As a basic proxy, you might liken this preferable future to Glen Albrecht’s symbioscene, a possible epoch where humanity, the technologies we design (and that in turn – given what Daniel Fraga has recently referred to as ontological design – design us) and the rest of the ‘natural world’ (yes, that preposterous fucking notion that the natural world is something ‘out there’ that is separate from us…) exist in balance. Such a world requires us to find ways beyond systemic ecological overshoot and rampant inequality and inequity. It requires us to progress beyond multipolar traps, our obsession with infinite growth and myriad perverse incentives. It requires us to move beyond arms races of all kinds. It requires us to first imagine, then act together, to biodegrade that which is unhelpful, while collectively crafting that which can meaningfully carry us forward, the seeds and saplings that might eventually become a thriving ecology for millennia to come.

Increasing the probability of such a preferable future – whatever form that takes, which will not be driven by some top-down homogeneous mandate, but rather some type of dynamic dance between the macro, meso and micro scales – likely requires us to embody relationality, love and an action oriented existential hopefulness.

Alright. Basic setup done.

Take a deep breath in, hold for a brief moment, slowly and purposefully release… Give thanks to the brilliance of your parasympathetic nervous system.

Ready? Let’s do it.

In ‘Techno-optimism: an Analysis, an Evaluation and a Modest Defence’, Danaher presents readers with an ‘Argument template for techno-optimism’. It goes:

(1) If (a) the good probably does or probably will prevail over the bad and (b) if technology probably plays a key role in ensuring this, then techno-optimism is the correct stance.

(2) The probable current and/or future facts are F1…Fn [Facts Premise]

(3) The agreed upon value criteria for determining whether the good prevails over the bad are V1…Vn [Value Premise]

(4) The good probably prevails over the bad, given F1…Fn evaluated in light of V1…Vn [Evaluation Premise]

(5) Technology probably plays a key role in ensuring that (4) is true (Technology Premise].

(6) Therefore, techno-optimism is the correct stance.

We use this as basic inspiration for our work below. But before moving, let’s clarify what might already be obvious. We refer to techne-optimism, rather than techno-optimism. In ancient Greek philosophy, tékhnē is a concept that refers to making or doing, and is modernly thought of as relating to practical knowledge. Because of our underlying metaphysics, value system and broader relational philosophy, this framing makes a heck of a lot more sense.

Our working definition of Tékhnē is the skillful art and craft of relationally applying knowledge, moral imagination and wisdom to reveal ‘reality’ through embodied praxis. Doing so based on the belief that such a collective and relational endeavour increases the likelihood of tomorrow being better than today is where optimism comes in (we discuss how this comes into tension with traditional views of optimism below).

A brief digression… One way to explore Metaphysics is through areas of philosophy that relate to it (and are sometimes thought of as existing ‘within’ it), namely ontology (what exists), epistemology (what can be known, how we can know it etc.), axiology (what we value and why) and cosmology (our story of the universe, the meaning we derive from this etc.). We aren’t going to dive deep into this ‘field’ in the essay you’re reading. We are working with too many practical constraints, and the reality is that such an endeavour is like an infinite unfurling of doorways through wilderland.

What does need to be clearly stated – the explicit point of this digression – is that nothing that humans describe (or perhaps experience for that matter) is metaphysically agnostic. Everything is imbued with assumptions about what exists and what can be known. These assumptions massively impact our capacity to sense-make. They frame how we relate to ideas. They’re implicated in, and give rise to, our very sense of life itself.

To better understand what we really mean by the claim, “nothing that humans describe is metaphysically agnostic”, allow us to introduce the Philosopher of Science, Bjørn Ekeberg. In this interview on the ‘shaky foundations of cosmology’, Dr. Ekeberg describes some of the challenges facing the Standard Cosmological Model. He highlights the very nature that, even within the ‘natural sciences’ (the ‘hard’ sciences if you will), there are powerful metaphysical assumptions all over the place*. You might find the Einstein example particularly useful.

*This is not to say that science is not incredibly useful, powerful and illuminating. It most certainly has been, can be and will continue to be. It is to suggest that science, like all human constructs, has limitations, is driven by assumptions and is grounded in narrative.

It’s pretty darn rare to talk about metaphysics or our deep underlying assumptions and beliefs. But just because it’s uncommon, doesn’t mean it’s not important. So, here we are.

We ‘know’ we operate in relation to metaphysical beliefs. We hold them fairly lightly. We try to make them as explicit as we can, but it’s likely many remain implicit. We can’t always grasp them with the limitations of language. With that said, Bucky does a decent job here:

With our digression done, defining a basic value system feels like the most useful place to go next. This impacts everything we do and think of as a team. It’s expressed through a dynamic dance of what we think exists, what we think we can know and our interpretation of the story of the universe.

To start with, let’s make a normative claim (something we believe ought to be done because it’s good and right): Humanity should actively work together to create a world where every person on this planet lives a healthy and dignified life, within biophysical limits (the ‘safe operating zone’ in relation to Earth System Boundaries).

You can think of this as our core value premise.

Within this, of course, there’s nuance. We can’t possibly cover the entire field of value theory or the ways in which we relate to it. Nor can we really describe everything that we value or we think we ought to value in some type of linear, dot point list (we’re not even sure that’d be helpful).

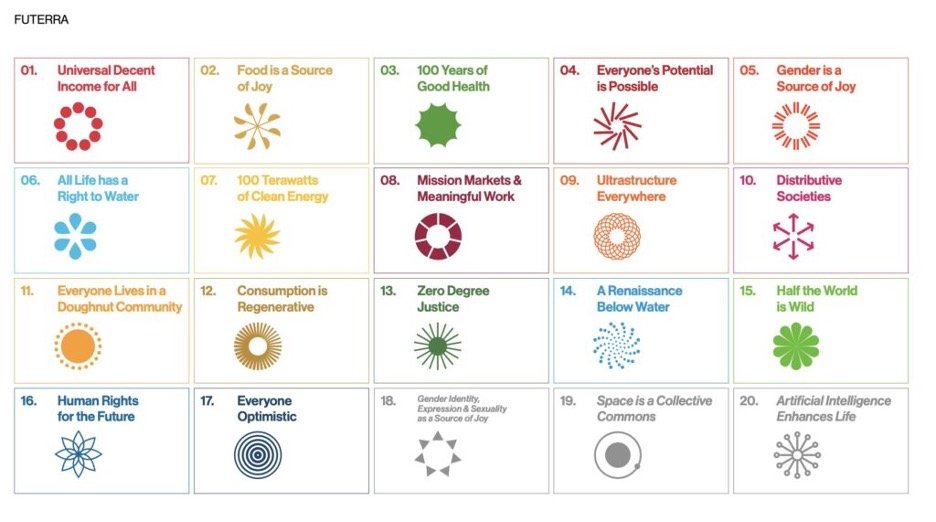

Instead, imagine there was some type of guiding value like the above. Now also imagine something like the below, taken from Futerra’s Awesome Anthropocene Goals, as the basic guiding framework that supports more specific action across the macro, meso and micro scales of connection, collaboration and coordination (something we describe in our response to the Australian Government’s Draft Science and Research Priorities).

This is the basic substance of what we value. It’s not an exhaustive description of course, but it should usefully support the rest of this essay.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Effects

illuminem briefings

Oil & Gas · Ethical Governance

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Insurance

Al Jazeera

Effects · Climate Change

Forbes

Sustainable Living · Climate Change

Japan Times

Climate Change · Effects