The virtues of water adaptation technologies

Unsplash

Unsplash Unsplash

Unsplash· 10 min read

The contribution of water and water conservation in support of human development cannot be overstated. Water sources such as from glaciers provide freshwater supply to communities for drinking, irrigation, and industry, support unique ecosystems and species, and contribute to climate regulation itself. However, since the mid-twentieth century, rising temperatures have spelled periods of unsustainably high melting rates for many glaciers, disrupting these natural services. This has been the case particularly in the Hindu-Kush Himalayas massifs, which feed ten major rivers sustaining the livelihoods of 240 million people in the mountains, and over 1.6 billion people downstream. The potentially catastrophic impacts of this trend require urgent and innovative adaptation strategies and technologies to secure water resources for the future.

In this insight, we highlight five technologies that can be used to manage accelerating glacial melting, exploring all three classifications of adaptation technologies utilised by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) and widely understood in the academic literature. These classifications are as followed:

• Orgware, or ‘organisational technologies’, referring to the organisational, ownership, and institutional arrangements necessary for successfully implementing sustainable adaptation solutions, such as Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) and watershed management.

• Hardware, or ‘hard technologies’, referring to the physical infrastructure and equipment on the ground, for example small-size solar-powered pumping systems (SIP) and mini/micro-hydropower (MHP) systems.

• Software, or ‘soft technologies’, referring to approaches, processes, and methodologies, such was water reallocation, necessary for adaptation.

Altogether, these technologies play a critical role in mitigating the impacts of accelerated glacial melt, ensuring water availability, sustainable irrigation, biodiversity protection, and enhanced resilience in affected regions. Moving forward, a combination of policy support, investment in technological solutions, and community engagement will be essential to scaling these solutions and safeguarding water security in a warming world.

Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) is currently the globally accepted approach to managing water and is essential to implement in the face of accelerated glacial melt. IWRM is defined by UNEP as the “coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources, in order to maximise the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems”.

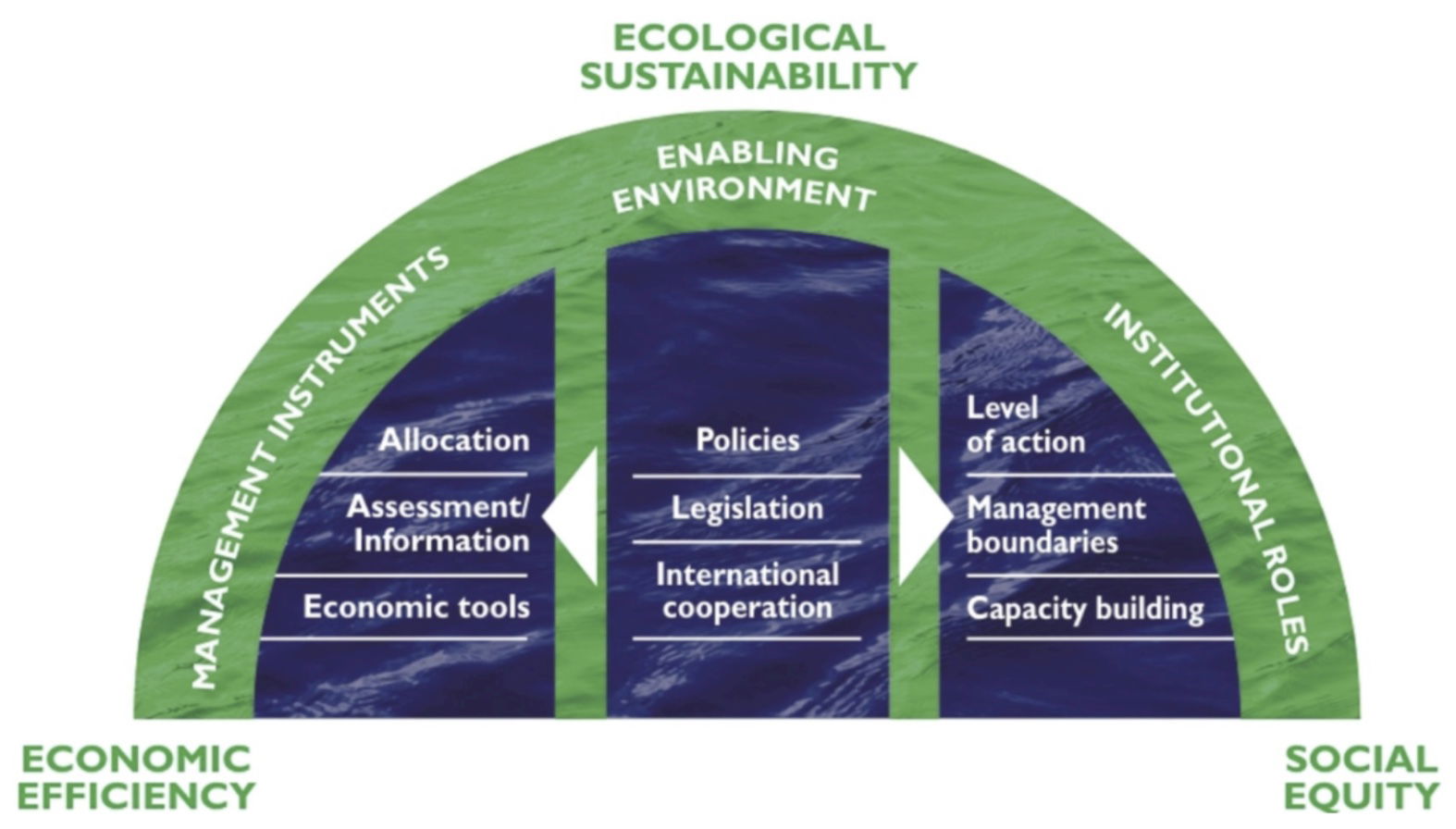

The IWRM approach focuses on three pillars (as visualised below):

• Enabling. An enabling environment of suitable policies, legislation, and strategies for sustainable water management.

• Institutions. Putting into place the institutional framework through which to put these into practice.

• Operations. Setting up the management instruments required by institutions to do their job.

In theory, the combination of these pillars allows water management to achieve ecological sustainability, social equity, and economic efficiency without compromising on each goal.

Visualisation of the IWRM approach (Global Water Partnership)

IWRM does deliver results. For example, the implementation of IWRM in regions such as the Andes has successfully led to a transition away from centralised and engineering-dominated modes of water governance, which are usually characterised by a focus on large infrastructure projects with little regard for their socio-ecological implications. Instead, IWRM has promoted innovative, adaptive management projects such as water funds, rewards for ecosystem services and nature-based solutions, and indigenous knowledge production. Nevertheless, IWRM is not a panacea and attention must be paid to the long-term sustainability of these community-based approaches. For example, research shows that in many regions, including the Andes, local institutional capacity to participate in IWRM has been degraded by a variety of social, political, and economic stressors including the impacts of previous top-down policies, market integration, and local corruption.

At a more local scale than IWRM, watershed management is an interdisciplinary practice linking land and water management in the effort to provide a sufficient source of quality water to both the human world and natural ecosystems. This approach recognises that land-use practices impact water quality through a variety of processes, with the challenge being to address these impacts coherently and comprehensively across a wide variety of soils, terrain, and land-use settings.

This is becoming particularly important as the impact of climate change on the water cycle becomes more apparent, due to increased variability and unpredictability, as well as greater frequency of high-intensity rainfall, floods, landslides and wildfires, having a large impact on agriculture and other economic and social areas.

Management practices are wide ranging and include tree planting, revegetation, terracing, damming, water harvesting, agroforestry and more. Examples of successful watershed management in the Western Himalayan region include the WWF-Pakistan Ayubia National Park project from 2009-2018, in which improved agricultural practices, irrigation systems, and alternative income generation activities were introduced with a special emphasis on women. Successfully implemented actions included protection of biodiversity, improvements to water filtration for locals, and enhanced monitoring of watershed management activities in the region.Sustainable watershed management practices have been shown to have a variety of benefits, with the World Resources Institute (WRI) categorising these as:

• Water quantity: aiming to reduce runoff/erosion, improve soil moisture and filtration, and increase supply.

• Water quality: aiming to reduce sedimentation, filter pollutants and reduce contaminants.

• Regulated flow: aiming to achieve flood and landslide prevention and the protection of habitats and infrastructure.

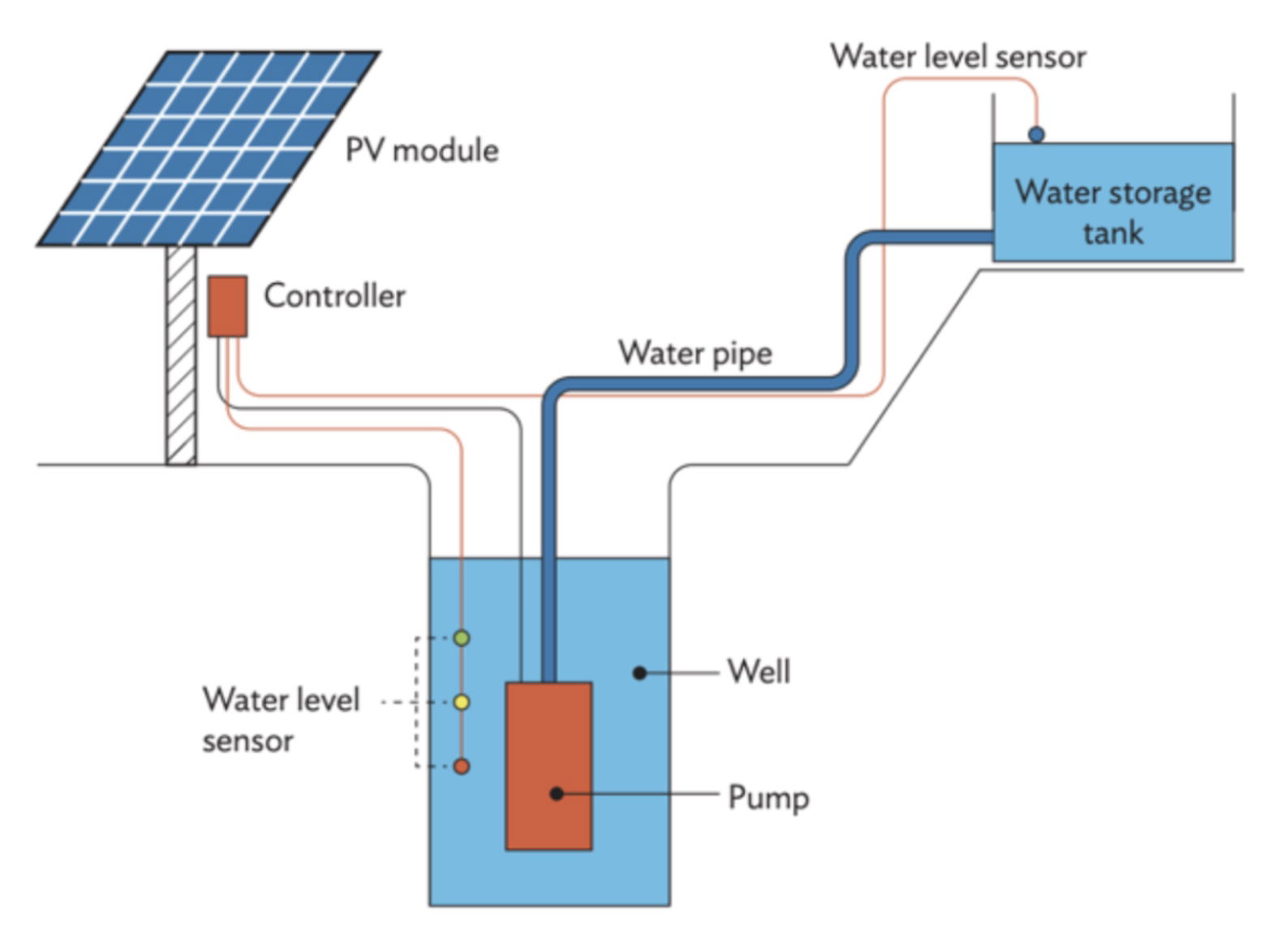

There are many emerging hard technologies that enable us to adapt to these issues more effectively. One of these is small-size solar-powered pumping, or Solar Irrigation Pump (SIP) systems: irrigation systems powered by PV modules that tell the pumps when to distribute water. They are an ideal match for irrigation as water can be pumped when solar irradiation is high.

Configuration of a SIP

SIP systems have many benefits over traditional irrigation pumps. Firstly, SIP systems reduce irrigator’s reliance on diesel fuel, reducing cost of agricultural production and accelerating the clean energy transition while reducing the incidence of water, air, and soil pollution. They also enable more efficient water resource use, as the systems can be designed to service individuals or a group of farmers, leading to a ‘professionalisation of irrigation practices’, and are easy to install, operate autonomously, and have low operation and maintenance costs. In some cases, they also enable users to sell surplus electricity to the grid, benefitting the entire energy system.

It is nevertheless important to manage the use of these pumps responsibly in community-driven management frameworks. As the marginal cost of pumping is zero, there is a risk of over-exploitation of surface and groundwater sources, leading to a potentially severe maladaptation risk. When promoting this technology, training and the establishment of management frameworks are critical elements in delivering successful projects.

Another key technology is micro-hydropower (MHP), essentially a power generation take on water mills. Modern MHP units consist of a water conveyance component that delivers the water (typically a channel or pipeline); a turbine, pump, or waterwheel, an alternator or generator, a regulator to control the generator, and wiring to deliver electricity. Irrigation canal hydropower specifically is the practice of installing these turbines in irrigation canals, enabling the generation of electricity by utilising existing water flows.

Hydropower generation potential stands to benefit from the impacts of climate change and accelerated glacial melt on water flows so long as there is sufficient planning, so impacted communities can harness sustainable, decentralised, sustainable and low-cost energy from these systems. From a capacity perspective, MHP systems are useful in developing country contexts due to their relatively easy installation and cheap operation on existing irrigation canals, avoiding issues such as the rehabilitation of people and environmental issues with larger hydropower plants. This form of MHP also does not disturb the main function of the irrigation canal to supply water to the irrigation system and can help provide power for the system itself, increasing sustainability.Finally, the introduction of managed flows can help regulate excess glacial melt and store water for increasingly erratic dry periods. The ponds created in this way can be used for fish-rearing and to support biodiversity. Careful design and planning are however needed.

MHP is a very common technology in Switzerland, with more than 1,400 systems at an installed capacity of 1,000 MW producing 4,100 GWh per annum, around 10% of the total hydropower generation. Many organisations in the country, including Cleantech Alps, have championed the use of MHP systems in existing or planned infrastructures, including irrigation, drinking water, wastewater and snowmaking, citing their minimal environmental impact and low investment cost. A guide to ’energy recovery in existing infrastructures with small hydropower plants’ has been produced by the company ’Mhylab’ and the European Small Hydropower Association (ESHA), providing several case studies of functional MHP systems in irrigation canals in Europe, the largest of which is located in Rino, Italy, producing 14,000,000 KWh/year, enough to power just over 3,000 European households.

Small hydro, Switzerland

Water reallocation is the transfer of water between users who have a formal or informal allocation of a specific amount of water – for example through water rights, permits, or agreements. The reallocation process could be triggered e.g. in cases when the current allocation becomes physically unfeasible, economically inefficient, or socially unacceptable. Water reallocation can take many forms, and can be driven by law/policy changes, economic feasibility, climate change, infrastructure degradation and development, population growth and more.

Water reallocation is a complex process that will require the balancing of multiple, competing interests through the engagement of all stakeholders. It can form an integral part of IWRM and sustainable watershed management. For example, diverting water for irrigation purposes from a reservoir feeding power generation could lead to reduced power generation and higher electricity prices. Similarly, overuse of water for low-value agricultural purposes such as the production of animal feed for export purposes, could reduce water volumes available for municipal and/or industrial use.

When these challenges are overcome, water reallocation injects much-needed flexibility into water systems, enabling them to share resources without additional investment in alternative water sources or infrastructure while providing environmental and social benefits. It also acts as an important component in water supply and demand management, enabling scarce water to be transferred from marginal/inefficient to higher-value/more efficient uses, providing additional water supplies to new or growing demands.

For example, due to climate change in the Peruvian Andes, glacial melt threatens to lead to long-term decline in available water where there is already existing competition between sectors, so the decision has been made to reallocate water from agricultural to urban uses. Similarly, in Coimbatore, India, growing urban demands including an emerging water-intensive textile industry have led to many formal and informal water transfers from rural to urban uses. Water reallocation for environmental benefits has also occurred, for example in China, where a portion of irrigation water supply from the Hei River Basin was ordered to be reallocated to ensure the maintenance of greater instream flows for ecosystem restoration efforts.

These examples highlight the need to ensure a balance is struck between different use-cases in water reallocation, with the example from China leading to farmers receiving financial support from the central government for more efficient irrigation practices to offset the reduction in irrigation water supply. While these cases underscore the challenges of balancing competing demands, they also reveal significant potential for water reallocation to mitigate the impacts of glacial melt and other water resource pressures, provided that careful planning and equitable support mechanisms are in place.

This article is also published on LinkedIn. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Steve Harding

Water · Nature

Diego Balverde

Effects · Water

Praveen Gupta

Effects · Mitigation

Financial Times

Power & Utilities · Water

BBC

Nature · Water

Eurasia Review

Carbon Capture & Storage · Water