The untold stories: what the energy transition looks like in a developing economy

· 7 min read

Currently, 24.9% of the Panamanian population is between the ages of 15 and 29, which means that a quarter of the country is represented by young people: a quality characteristic of developing countries. What does the energy transition look like here and now, where efforts to advance the energy transition are surrounded by difficult social conditions, especially for the younger population? What does it mean for children and young people in rural villages to talk about a just and inclusive energy transition?

At the beginning of March 2022, I went with UNICEF Panama on an awareness-raising mission aimed at the student population of different rural schools that had environmental programmes in place, to promote a survey on renewable energies that we built in the non-profit organisation I co-founded called Youth and Climate Change, in alliance with UNICEF.

This led me to visit La Bonga, a village located in the western part of town, in the mountain range, a three-and-a-half-hour drive from Panama City, where a high percentage of the population has only basic education (first 6 years of schooling) and the work sector is mainly the agricultural sector.

Figure 1. On the way to the nature trails surrounding the multi-grade school of La Bonga, in the company of the children

On our way, we came to a multi-grade school of the same name. A multi-grade school is a type of school where a teacher gives lectures to two or more grades simultaneously in the same classroom [1]. It is a school model characteristic of rural Latin America, and this is, for example, teaching 5th and 6th grade classes together because there is not enough student population to have separate classes, or enough educators to teach separate groups. This was precisely the case of the school of La Bonga.

The survey consisted of raising awareness about energy consumption and its impact on the climate crisis, and how much children in the area knew about the issue, through UNICEF's U-Report platform that works with a WhatsApp Chat Bot and whose data collected, aims at a participatory democracy from the perspective of youth input to decision-makers [2]. To conduct the survey, we had to walk with the group of children to a small Catholic chapel located on a hill where there was better access to internet signals.

More than 250 children from all over the country, and not only from the village of La Bonga, commented that they knew that energy consumption influenced climate change (see illustration 2).

Figure 2. Child taking the survey via UNICEF's U-Report Chat Bot. In the text you can read in English: Do you consider that energy consumption influences climate change? Answers a) yes, b) no, c) don't know.

It was only in 2020 that work began to supply power to the village and other parts of the area through the rural electrification office. Prior to this date, guarichas (small kerosene-powered lamps), candles and firewood for cooking were still part of the daily life of the resident families.

For some children, wanting their "school to have solar panels and not run-on fuel because it pollutes the environment" is a possibility. The Latin American region possesses enormous natural resources, such as its existing water, wind and solar potential. Proof of this is that Panama, according to data published by the Latin American Energy Organisation (OLADE), has more than 80% of its electricity generation from renewable sources, ranking 8th in the world in terms of clean energy [3]. However, this high percentage is due, as in many countries of the region, to its dependence on energy from hydro sources rather than a diverse energy mix. In 2021, 81% of Panama's electricity generation was produced by renewable sources: 70% from hydro and 10% from solar and wind [4].

The region's dependence on hydroelectric power raises concerns about the vulnerability of hydrological cycles over the last decade, so imagining their school powered by solar energy, as one of the children suggested, is not such a foreign idea to think about in the near future.

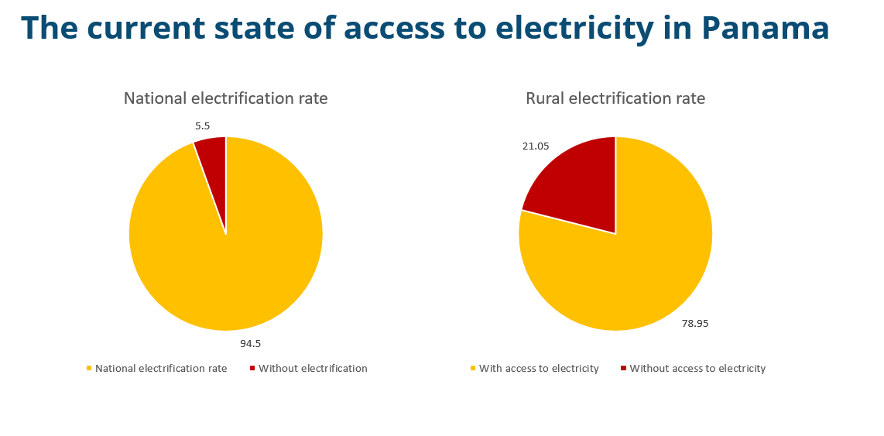

And even though 80% of the energy matrix is renewable, there are still villages where the energy isn’t available, cutting off possibilities of higher education or better living conditions. Illustration #3 shows that currently, the country's rural electrification rate indicates that 78.95% have access to electricity, while 21.05% of the rural population does not have access. It doesn’t seem like bigger numbers, but in other words, 3,948 communities or 46,259 households in the country will not have access to electricity under the current energy concession model.

Figure 3. The current state of access to electricity in Panama [5]

The next stop on my journey took me to the Playa Chiquita school, about an hour from the city, in a small rural village bordered by mangroves and with an interesting condition: it was located on a former open-air rubbish dump, which had now been filled in for the construction of the school and was now a model of environmental development. At the highest point of the land, you were able to see the sea, and the gentle breeze blowing almost made you forget that at some time, the place was full of waste.

The school was practically self-sustainable: they had vegetable gardens, animal farms, areas dedicated to cultivation where the crops were used for school consumption and the surplus was sold, thus generating extra income for the school's operation. Except for energy, which came from the national grid, and who’s reliable wasn’t the best.

According to the survey results, 8 out of 10 participating children and young people believe that laws and educational talks should be promoted to help bring about a shift towards the development of cleaner energy [6]. When asked if they had a message for the country's leaders on the energy issue, they replied:

"The technologies and options exist to be able to make the energy transition and also to bring energy to the most distant communities, what is needed is the will on their [decision-makers] part. It is time to act.”

"The power is with them [decision-makers], we are just the voice, they have more power than us, therefore, they can do more."

However, in the countries of the Latin American region, the engagement of the population in climate and energy transition issues is difficult due to the level of economic and social development, coupled with more urgent problems to solve, such as those suffered by the people of La Bonga and Playa Chiquita in terms of access to basic needs such as internet, education, transport or health, which means that decisions on when, where and how to invest in energy transition end up being resolved at desks, sometimes with little participation of society, not by choice but by circumstances [7].

Figure 4. The children of Playa Chiquita during the survey

The need for a just and inclusive energy transition becomes even more urgent when the degree of vulnerability that people face because of climate change is higher. An example of this issue is that the first human displacement in Latin America due to climate change is occurring here in Panama, where more than 1,200 people will have to leave the island of Gardí Subdug (Isla Cangrejo in Spanish, Crab Island in English), home to an indigenous community of the Guna Yala, for the mainland, in search of refuge and where it is estimated that a high percentage of the climate displaced are children and young people.

The untold stories of La Bonga and Playa Chiquita taught me that we still have a long way to go if we want to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals: energy access for all, and that to show the real stories of the energy transition and its impact on people, we first need to humanise energy, not forgetting that the end product is intended to improve energy poverty, education in schools, to enable greater connectivity in rural areas, and to make life easier in general.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Oil & Gas · Ethical Governance

Jonathan Lishawa

AI · Energy Transition

Olaoluwa John Adeleke

Power Grid · Power & Utilities

The Wall Street Journal

Natural Gas · Oil & Gas

Financial Times

Oil & Gas · Upstream

Forbes

Nuclear · Power & Utilities