· 7 min read

Introduction

In opinion polls, “too much plastic” constantly ranks as one of the most pressing environmental concerns (Agyepong-Parsons, 2020). Overproduction and overconsumption of plastics have led to a severe negative externality on our environment, especially our oceans. To combat this issue, market-based solutions must be implemented rapidly by governments to reduce the amount of plastic we use and to promote recycling within their own borders. In this article, I will first highlight the harsh consequences of the marine plastic pollution market failure. Furthermore, I will shine a light on the complex relationship the UK has with its plastic waste. Lastly, policy instruments that can be used to internalise this negative externality will be presented, as well as the difficulties associated with these policies.

What is the problem?

Since the 1980s, there has been a multitude of studies on the negative externality that plastic has on ecosystems and wildlife. Although there remains some uncertainty about the extent of the impact of plastics on our environment, plastic pollution of the marine environment is increasingly understood as a serious ecological problem. This is due to the chemical durability of plastics and their fragmentation into micro- and nano-plastics which can be ingested by small organisms such as zooplankton and move up the food chain. Every year, an estimated one million seabirds, as well as 100,000 sea mammals and turtles, are killed by plastics (IUCN, 2021) due mainly to entanglement or ingestion. Indeed, plastic bags and packaging are the most deadly forms of plastic in our oceans, but discarded fishing gear also plays a major role (United Nations Ocean Conference, 2017). These negative externalities on the environment highlight the presence of a market failure, as countries have not acted in a major way to curb the plastic pollution problem and internalise it into prices and legislation of their country. This pollution leads to a tragedy of the commons where no country is incentivised to bear the cost of cleaning up the ocean.

The truth about plastic waste recycling in the UK

Looking at the UK specifically, the recycling capacity of plastic waste is insufficient. Every year, local authorities collect an estimated 2.3 to 2.4 million tonnes of plastic packaging, primarily from households (Eunomia Research & Consulting, 2018). However, according to RECOUP (2020), an organisation formed to encourage recycling, the UK recycles just 230,000 tonnes of domestic plastic packaging per year, implying that only around 10% of household plastic packaging gets recycled within the UK. The rest is too difficult to recycle or is exported to be recycled in the Global South. In 2019, the UK exported 61% of its plastic packaging for recycling, mainly to countries like China, Turkey, and Malaysia (British Plastic Federation, 2021). The quantity of plastic sent overseas has increased sixfold while the total number of plastic packaging recycled in the UK has stagnated since 2002.

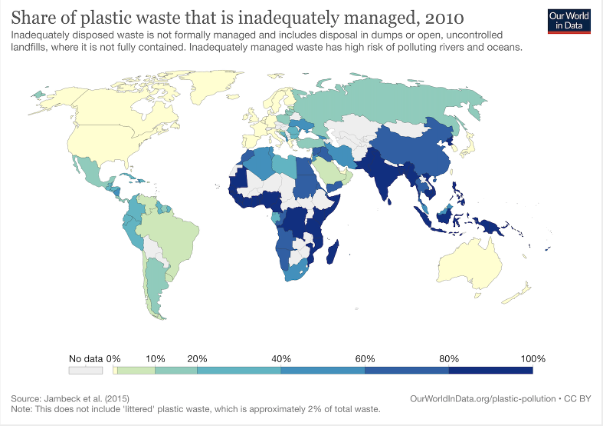

This waste management strategy is unsustainable, particularly in light of increased environmental regulation in the Global South. Turkey and China, for instance, have banned imports of most types of plastic waste as a reaction to the increased pollution within their borders and as a means to improve their international reputation (to not be seen as a waste dump for the Global North). The issue is that plastic exports are not reliably monitored, and no effort is taken to guarantee that the plastic does not end up in poorly managed landfills or illegal dumping, a problem that is widespread in the Global South (Figure 1). A study by Bishop et al. (2020) estimates that up to 31% of the plastic sent for recycling abroad might not be recycled at all. Weak international institutions, uneven regulations, and unequal North-South relations are at the root of the problem.

What can be done to combat this issue?

In order to halt this reliance on exports to countries in the Global South that mismanage waste, more investment needs to be diverted into the UK's recycling capacity (British Plastic Federation, 2021). The Government could implement several policies at the same time to combat this issue. Indeed, I believe that having multiple policies that are tailored to influence certain behaviors would be the most effective. Firstly, the Government could subsidise the construction of new plastic recycling plants by proposing to fund a percentage or the full amount of the fixed costs necessary to start building new plants. Simultaneously, it could announce a ban on exports for plastic recycling by a specific date (e.g. 2030). The idea would be to have a certain amount of time for the sector to prepare and to have new recycling plants ready to function by that date. As with the ban on combustion engines in 2030 in the UK, it is important to have this delay period so that the sector can react slowly and not cause too much socio-economic disturbance.

The problem is not only that we export too much plastic, but also that we use too much of it. Notably, plastic packaging is especially unsuitable for recycling in practice, and other types of plastic also degrade in quality each time they get recycled. As a result, it is critical for the UK to reduce the quantity of plastic generated in the first place (Greenpeace, 2021). To reduce the amount of single-use plastic and thus plastic required to be recycled, the Government can put in place new regulations facing supermarkets. As an example, the French Government decided this year (as part of a new environmental bill) to enforce a ban on plastic packaging for most fruits and vegetables for sale in the country, starting in January 2022 (France24, 2021). Supermarkets can also be forced to have a certain number of packaging-free aisles with refill stations. This has also been decided this year in France, where now a fifth of aisles are required to contain refill stations by 2030. This will incentivise consumers to bring in alternative reusable shopping containers and bags and would be a major step in the circularisation of the British economy.

What are the challenges?

There are several challenges facing the solutions mentioned above. Firstly, making sure that UK households become better at recycling their plastic waste will require nudges and incentives from the government, but changing behaviours takes a lot of time. Another problem is how the government is going to get that capital. There might be more pressing problems according to the government since UK citizens might not be affected directly by this plastic waste. Allocating a portion of their budget to that might require the government to raise more money (by increasing taxes) or reduce funding for another issue, such as climate change mitigation, which might affect the Global North more than plastic waste. However, we can see that these topics are interconnected as plastic waste mismanagement contributes to climate change, through for example incineration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the problem of plastic waste is a global one that requires cooperation from countries around the world. Rather than passing the challenge to the Global South, the UK and other countries in the Global North should take on the responsibility for the waste that they generate. Otherwise, the fact that plastic waste is out of sight acts as an incentive to produce plastic indefinitely and creates issues when it is exported to countries with mismanagement practices and illegal dumping. Taxes might not be the way to go, but nudges can be put in place in supermarkets, such as through the implementation of packaging-free aisles with refill stations or bans on certain types of packaging that can easily be replaced. A topic that might accelerate policy implementation in this area is the impacts of micro- and nano-plastic particles on human health. Truly, in our anthropocentric world, we tend to react in a delayed manner to things that don’t impact us directly.

References

Agyepong-Parsons J (2020). Plastic pollution tops list of public’s environmental concerns, survey finds [online]. Ends Report.URL: www.endsreport.com/article/1696048/plastic-pollution-tops-list-publics-environmental-concerns-survey-finds [Accessed 30 November 2021].

British Plastic Federation (2021). Exporting Plastic Waste for Recycling [online]. URL: https://www.bpf.co.uk/press/exporting-plastic-waste-for-recycling.aspx[Accessed 5 December 2021].

Eunomia Research & Consulting (2018) ‘Plastic packaging: Shedding light on the UK data’ [online]. URL: www.eunomia.co.uk/reports-tools/plastic-packaging-sheddinglight-on-the-uk-data [Accessed 30 November 2021]

France24 (2021). France to ban plastic packaging for fruit and vegetables from January 2022. [online]. URL: https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20211011-france-to-ban-plastic-packaging-for-fruit-and-vegetables-from-january-2022 [Accessed 1 December 2021]

Greenpeace (2021). Trashed. How the UK is still dumping plastic waste on the rest of the world. [online]. URL: https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Trashed-Greenpeace-plastics-report-final.pdf [Accessed 1 December 2021]

IUCN (2021). Issues brief: Marine plastics. International Union for Conservation of Nature [online]. URL: www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/marine-plastics [Accessed 30 November 2021]

Our World in Data. URL: https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution [Accessed 30 November 2021]

United Nations Ocean Conference (2017) “Factsheet: Marine pollution”. [online]. URL: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Ocean_Factsheet_Pollution.pdf [Accessed 1 December 2021]

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.