The natural resources trap is alive and kicking

· 10 min read

One year ago, I published my book From Dutch Disease to Energy Transition [1], in which I analysed why countries with abundant natural resources (oil, gas, copper, diamonds, etc.) are struggling so hard to turn this ‘manna from heaven’ into a blessing rather than a curse. More often than not, the exploitation of those natural resources ends up crowding out other sectors such as the manufacturing industry, thereby depressing long-term economic growth (Dutch Disease). Furthermore, resource-rich countries tend to be less democratic and more prone to corruption and violence or even (civil) war compared to resource-poor countries (Resource Curse). [2] One year on, I am keen to take stock of any progress worldwide. The good news is that I have detected widespread awareness of the high risks for resource-intensive countries of succumbing to Dutch Disease and Resource Curse. The bad news is, however, that barring a few rare exceptions, these countries seem stuck in a ‘natural resources trap’. Several new oil and gas-producing countries like Guyana and Namibia are trying to avoid falling into this trap, but the jury is out on whether they will succeed. Meanwhile, revenues from natural resources keep fuelling wars and civil conflicts in many regions, most notably the horrifying war in Ukraine.

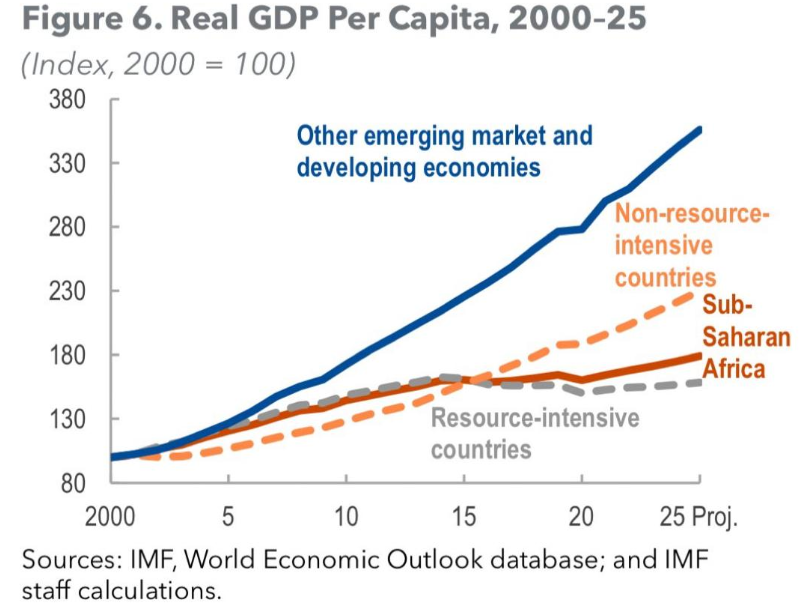

According to a long-standing narrative, the challenges posed by Dutch Disease and the Resource Curse are so overwhelming that they tend to depress economic growth in resource-abundant countries. Unfortunately, the graph below shows that recent IMF evidence seems to confirm this trend for the last 25 years.

The graph makes painfully clear that resource-rich countries have experienced consistently lower per capita economic growth this century compared to non-resource intensive countries, despite many enjoying a strong oil boom. The literature on the role of Dutch Disease and the Resource Curse in crowding out the manufacturing industry and depressing growth is still continuously expanding. [3] Recent opinion pieces include analysis of e.g. Chad, Equatorial Guinea, South Africa, Australia and the US. [4] Finkel and I attribute the low labour productivity and excessively high costs of transmission lines in Australia to Dutch Disease, whereas Gros sees a direct link between the declining manufacturing industry in the US and Dutch Disease. [5] In Gros’ view, this impact is more important than imports from China.

For the ‘new kids on the block’, the huge challenge is avoiding falling into the Natural Resources Trap. The new oil state Guyana just burst into the IMF’s top ten countries by GDP per capita, but can they sustain this, while preparing wisely for the post-oil future? The same key question applies to countries like Namibia, Niger, Guyana, Suriname or Jamaica, where they recently reported significant oil discoveries. [6] It is encouraging to see healthy public debate on these issues in Guyana [7] and Namibia, [8] but this in itself doesn’t necessarily translate into the appropriate policies to avoid or mitigate the formidable challenges of Dutch Disease and Resource Curse. [9] Guyana has already been called ‘the test case for the resource curse In the 21st century’. [10]

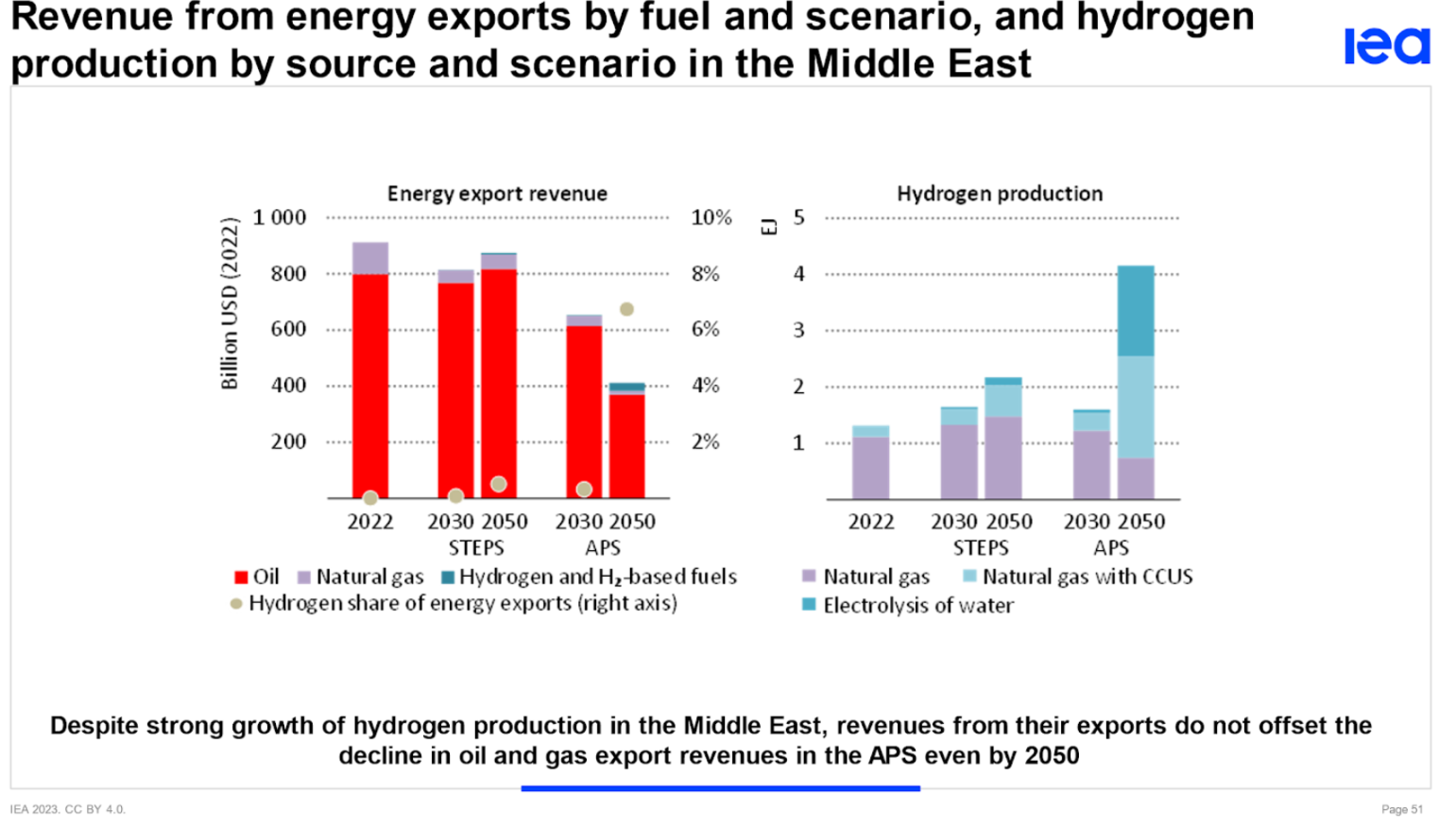

Despite severe headwinds in many countries worldwide over the last year (see, e.g. the farmers’ protests in Europe, and citizens’ anxiety about high energy prices), the global energy transition is still advancing, as demonstrated by recent IEA analysis. The investment in clean energy across the world is now almost double the investment in fossil fuels and is set to exceed $2 trillion in 2024, the highest level ever. [11] China, the US and the EU are leading the way, with many emerging and developing countries still lagging. At COP28, global leaders reached a significant agreement on tripling renewable energy, doubling energy efficiency, reducing methane emissions and, for the first time, starting to transition away from fossil fuels. In short, the global energy transition is now unstoppable and a more significant existential threat for fossil fuel-producing countries than ever before. Recent IMF analysis confirms this. [12] Granted, the road will be long and bumpy, but the direction of travel is beyond any doubt. We should of course, acknowledge that the drivers for the energy transition extend well beyond mitigating climate change and now include strengthening energy security and building up capacity in the new clean energy manufacturing industry (solar, wind, batteries, electrolysers, heat pumps, etc.). This sector has now become a major engine of economic growth and jobs, which at least partly explains why ever more countries around the world are embarking on green industrial policies. [13] One example is that an increasing number of countries with abundant renewable energy resources are eyeballing the build-up of a clean hydrogen export industry. [14] As many fossil fuel-producing countries, for instance, in the Middle East, also intend to become clean hydrogen exporters, it is essential to keep in mind that this avenue will only partly compensate for the loss of fossil fuel revenues. The graph below illustrates this point clearly.

Source: IEA, World Energy Outlook 2023.

It is therefore very understandable that many resource-rich countries are attempting to push economic diversification in other areas. One of these areas is an industrial policy focused on developing downstream sectors, sometimes using measures like trade tariffs or outright bans on exporting raw materials. An example is Indonesia stopping the export of nickel and aiming to develop a nickel refining industry. At the same time, Indonesia’s sovereign wealth fund is investing $1 bn in the energy transition. [15] We can expect many more countries to move in this direction in the near future, as the scramble for critical minerals will intensify. [16]

As highlighted in my book, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Oman stand out among oil-producing countries in consistently pursuing an economic diversification strategy and, more importantly, making tangible progress, thus supporting the compelling narrative. Over the last year, we have seen further advances in this area, ranging from final investment decisions on big low-carbon hydrogen projects to moves in sectors like petrochemicals and tourism. [17] A striking example is that Saudi Arabia is set to become the world’s biggest construction market due to projects aimed at diversifying the economy. [18] Saudi Arabia is also installing about 1 GW of solar capacity per month. [19] The progress on economic diversification is also corroborated by advances in the economic complexity of the export performance of the three mentioned Gulf countries. It remains remarkable that in terms of advancing economic diversification, these Gulf countries seem to be outperforming oil and gas-producing countries like Australia, Canada and Norway. [20]

Many resource-rich developing countries, however, need help with advancing the energy transition and diversifying their economies. [21] In particular, they are facing increasing indebtedness and worsening credit ratings. [22] Unfortunately, the world has made little progress in providing the required multilateral funding to help finance the energy transition of developing countries, while rising interest rates are pushing many of them to the brink. [23] We can only hope that COP29 in Azerbaijan will finally achieve meaningful results in this field.

The tragic reality is that the oil and gas revenues of Russia keep fuelling the war in Ukraine, despite the efforts of North America and Europe to stop this. [24] The main impact of the sanctions against Russia appears to be the reallocation of Russian oil and gas towards Asian consumers against discounted prices, with even Europe still importing significant volumes of LNG from Russia. More recently, the energy infrastructure in Ukraine has become a key target in the war itself, [25] a stark reminder of the historically critical importance of energy sources to fuel the warfare machinery in World Wars I and II. [26]

In other parts of the world, natural resources seem in one way or another closely connected to the flaring up of civil conflicts (and coups) in, e.g. New Caledonia, Mozambique, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Venezuela has laid claims to Guyana’s oil-rich Essequibo region. Apart from human suffering, severe conflicts tend to have profound and long-lasting negative economic consequences. For countries in the Middle East and Central Asia, the IMF has calculated that even a decade after a severe conflict, their real GDP per capita remains about 10% lower than before the conflict. [27] The international community, including NGOs like the Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) and the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), will need to keep doing its utmost to contain and mitigate the risks of the Resource Curse.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

1 Noé van Hulst, From Dutch Disease to Energy Transition, CIEP, June 2023, available on www.ciep.com

2 See my blog, Excerpts from ‘Dutch Disease to Energy Transition’, Illuminem, Dec 07, 2023.

3 E.g. Rabah Arezki et al., ‘The import channel of the resource curse’, VOX EU CEPR, 11 Jul 2024; Ramzi A.A. Hasan, ‘Dutch Disease and the Future of the GCC Economies’, Journal of Investment, Banking and Finance, 2 (1), Apr 29, 2024.

4 Harry Verhoeven & Théophile Pouget-Abadie, (No) Power to the People: Oil and the Politics of Energy Access in Chad’, Center on Global Energy Policy, Columbia/SIPA, February 05, 2024; Ken Opalo, ‘What next for Equatorial Guinea after oil?’, An Africanist Perspective, Feb 20, 2024; Ross Harvey, ‘Dutch Disease and what to do about it in South Africa’, Good Governance Africa, May 23, 2024; Daniel Gros, ‘A Trade Policy for the Middle Class Will Not Save US Manufacturing’, Project Syndicate, Jul 11, 2023; Alan Finkel and Noé van Hulst, ‘Speeding up the global energy transition’, Illuminem, Oct 26, 2023.

5 On the US, see also Patrick Artus/Natixis, Flash Economics, June 19, 2024 [no 284].

6 ‘Explorer ramps up pitch on Jamaican oil prospects’, The Gleaner, May 29, 2024.

7 ‘Guyana Is Trying to Keep Its Oil Blessing From Becoming a Curse’, Bloomberg. 16 February 2024.

8 Including a stark warning of the Bank of Namibia governor Johannes Gawaxab, Namibia Economist, April 5, 2024.

9 The reportedly best film about the resource curse is Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon; see Ed Crooks on X on 30 October 2023.

10 ‘Guyana: the world’s last petrostate?’, Financial Times, 25 June 2024.

11 IEA, World Energy Investment, June 2024.

12 IMF, Key Challenges Faced by Fossil Fuel Exporters during the Energy Transition, IMF Staff Climate Note 2024/1.

13 See my blog ‘Anatomy of a fall: Europe’s deindustrialisation’, May 09, 2024.

14 Anne-Sophie Corbeau & Rio Pramudita Kaswiyanto, What Do National Hydrogen Strategies Tell Us About Potential Future Trade?, Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia/SIPA, May 2, 2024.

15 ‘Indonesia wealth fund focuses on energy transition with $1 bn plan’, Financial Times, 23 April 2024.

16 Thomas Reilly, ‘African Raw Material Export Bans: Protectionism or Self-Determination?’, Global Policy Watch, May 21, 2024.

17 See the chapter on Saudi Arabia in: Robert D. Kaplan, The Loom of Time: Between Empire and Anarchy, from the Mediterranean to China, Penguin Random House, 2023. and ‘Call of the desert’, The Economist, July 6th, 2024, on Saudi tourism.

18 Bloomberg, 25 June 2024.

19 Dave Jones on X, 29 May 2024.

20 See chapter 3 of my book and recent pieces like ‘Fossil fuel giant Norway pitches itself as Europe’s ideal green partner’, Politico, Apr 23, 2024; Robin Mills, ‘Is Australia’s energy transition losing track?’, The National, May 06, 2024; Simon Mundy, ‘Canada faces a long road ahead to arrive at cleaner energy mix’, Financial Times, 20 June 2024.

21 For a recent analysis of Nigeria’s situation, see Ken Opalo, From An Africanist Perspective, ‘Why exactly are major international firms leaving the Nigerian market?’, Jun 19, 2024.

22 Guy Prince, ‘Petro States of Decline: oil and gas producers face growing fiscal risks as the energy transition unfolds’, Carbon Tracker, 01 December 2023.

23 See Lawrence H. Summers & N.K. Singh, ‘The World Is Still on Fire’, Project Syndicate, Apr 15, 2024.

24 Currently EUR 664 million per day, see the weekly updates of Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA).

25 ‘Russia hits Ukraine energy infrastructure in large-scale missile, drone attack’, Politico, 1 June 2024.

26 See chapter 2 of my book.

27 ColombeLadreit, Scars of Conflict Are Deeper and Longer Lasting in Middle East and Central Asia, IMF Blog, June 5, 2024.

illuminem briefings

Hydrogen · Energy

illuminem briefings

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

Vincent Ruinet

Power Grid · Power & Utilities

World Economic Forum

Renewables · Energy

Financial Times

Energy Sources · Energy Management & Efficiency

Hydrogen Council

Hydrogen · Corporate Governance