Verified impact reporting: Why boards can no longer afford green bond complacency

Unsplash

Unsplash Unsplash

Unsplash· 16 min read

The green bond market has reached a critical inflection point where voluntary post-issuance reporting must evolve into mandatory verified impact measurement. With USD 672 billion in annual issuance and 74% of issuers already providing allocation reports showing where proceeds were spent², the basic reporting infrastructure exists — but independent verification of actual environmental outcomes remains dangerously inconsistent. This article examines how converging regulatory frameworks (EU, SFDR, proposed SEC climate rules), legal precedents (McVeigh v. REST, Milieudefensie v. Shell, Finch v. Surrey County Council), and market forces are transforming green bond governance from reputational opportunity into legal obligation.

Drawing on fundamental governance principles of trust, transparency, and accountability, and OECD Development Assistance Committee evaluation criteria, we propose that boards must treat verified impact reporting as a universal governance duty rather than competitive choice. The Indonesian Green Sukuk case study illustrates verification failures that would expose directors to liability under evolving standards, while Germany's twin green bond program demonstrates effective verification, preserving market confidence. Enhanced verification costs are minimal — typically USD 10,000– 150,000 per issuance¹ — but protect USD 275–550 million in greenium benefits while avoiding regulatory sanctions and fiduciary breach claims.

• CBI — Climate Bonds Initiative

• COSO — Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission DAC — Development Assistance Committee (OECD)

• ERM — Enterprise Risk Management

• ESMA — European Securities and Markets Authority

• ESG — Environmental, Social, and Governance

• EU GBS — European Union Green Bond Standard

• GSS+ — Green, Social, Sustainability, and Sustainability-linked bonds

• ICMA — International Capital Market Association

• MAS — Monetary Authority of Singapore

• OECD — Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

• SEC — Securities and Exchange Commission

• SFDR — Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation

• UKSC — United Kingdom Supreme Court

• USD — United States Dollar

The green bond market has reached a critical inflection point where what began as a voluntary exercise in corporate responsibility is rapidly becoming a legal and fiduciary imperative that boards can no longer delegate to sustainability teams.

Regulatory frameworks like the EU's Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)³ and the SEC's proposed climate disclosure rules⁴ are transforming green finance from reputational opportunity into compliance obligation. For corporate boards, this evolution demands moving from process monitoring to outcome verification.

Where environmental commitments once generated positive press coverage and modest greenium pricing benefits of 5–10 basis points⁵, they now carry enforceable disclosure obligations and potential liability exposure rooted in established legal precedent.

This transformation reflects three converging forces:

The EU Green Bond Standard (Regulation 2023/2631) mandates external verification through ESMA accredited reviewers⁴. Similar frameworks are emerging across major markets, including Singapore's MAS Green Finance Taxonomy and the UK's Green Taxonomy⁵. The voluntary ICMA Green Bond Principles⁶, while widely adopted, no longer provide sufficient protection against regulatory scrutiny.

Major asset managers have committed to net-zero portfolios, with BlackRock's 2024 stewardship report explicitly demanding "verifiable ESG outcomes rather than process compliance"⁷. These institutions manage USD 20+ trillion in assets and increasingly view unverified green claims as fiduciary risks. Yet "verifiable stewardship" remains contested, with shifting expectations across jurisdictions and time periods, making consistent compliance frameworks difficult to establish.

ESG litigation establishes clear precedent for environmental liability. The landmark McVeigh v. REST settlement (Federal Court of Australia, 2020) established pension fund trustees' duty to consider climate impacts⁸. Milieudefensie v. Shell (District Court of The Hague, 2021) held directors liable for failing to align corporate strategy with climate targets⁹. Finch v. Surrey County Council [2024] UKSC 50 established comprehensive climate impact verification requirements¹⁰. In the U.S., SEC v. Vale S.A. (2023) demonstrated SEC willingness to pursue ESG fraud cases¹¹, while BT Pension Trustees v. Moore [2023] EWCA Civ 875 clarified UK fiduciary duties regarding climate risk disclosure¹².

The evolution from voluntary to mandatory verification finds its foundation in fundamental governance principles that boards have long understood: trust, transparency, and accountability. These principles provide clarity where regulations remain ambiguous and establish the ethical framework for responsible stewardship.

Without credible verification, the green bond market risks systemic collapse. Unverified claims would erode investor trust, eliminate pricing advantages, and trigger regulatory sanctions. Verified reporting is therefore indispensable to preserve both market credibility and financial stability.

Directors have a fundamental duty to ensure that representations to stakeholders — whether investors, beneficiaries, or the public — are accurate and verifiable. Misstating environmental impacts exposes directors to liability by misallocating stakeholders' capital and preventing informed decision-making. Verified outcomes are essential to protect against fiduciary breach claims and securities law enforcement.

This governance foundation strengthens legal arguments around misrepresentation and fiduciary breach while providing universal principles that transcend jurisdictional differences in regulation. As noted by Eilís Ferran in her Oxford Business Law Blog commentary, "post-issuance accountability represents the next frontier in ESG fiduciary duty evolution"¹³.

Traditional board oversight focused on financial performance, risk management, and regulatory compliance. Sustainable finance introduces a fourth pillar: verified impact reporting (defined as independently confirmed measurement of environmental outcomes against stated objectives).

Boards must ensure green bond commitments align with broader corporate strategy, evaluating whether financed projects deliver measurable environmental benefits that justify their cost of capital.

Green bond project failures create multiple risk vectors including stranded capital, regulatory investigations, and liability exposure from technical feasibility issues, policy reversals, and climate-related disruptions.

Regulatory frameworks and investor expectations require boards to treat truthful impact reporting as a universal standard, not a competitive choice, preserving the credibility of green finance markets for all participants.

Green bond standards exhibit significant variation in verification requirements, creating regulatory arbitrage opportunities:

Global voluntary framework relying on second-party opinions with market reputation enforcement. Focuses on allocation reporting without mandatory outcome verification.

EU mandatory framework requiring ESMA-accredited external review with regulatory sanctions. Emphasizes enhanced disclosure and taxonomy compliance but limited outcome measurement.

Development finance framework requiring independent evaluation with published assessment. Provides six-criteria outcome measurement (relevance, coherence, effectiveness, efficiency, impact, sustainability)¹⁴ with counterfactual analysis and long-term benefit assessment.

At the federal level, the SEC adopted climate disclosure rules in March 2024 that would have required independent assurance of Scope 1 and 2 emissions for large filers. After extensive litigation, however, the SEC announced in March 2025 that it would no longer defend the rules in court, effectively pausing their implementation. This retreat highlights the limits of federal regulation in setting binding verification standards.

At the state level, momentum continues. California’s Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act (SB 253) and Climate-Related Financial Risk Act (SB 261) mandate Scope 1, 2, and eventually 3 emissions disclosure, backed by third-party assurance and penalties of up to USD 500,000 per year. These state frameworks now represent the most stringent U.S. requirements for verified climate reporting, effectively creating a two-tier system where multinational issuers face state obligations despite federal withdrawal.

For boards, the lesson is clear: federal inaction does not reduce liability risk. The SEC still pursues ESG misrepresentation cases under securities law (SEC v. Vale S.A., 2023), while state statutes and global regimes (EU CSRD, EU GBS) impose direct verification duties. Boards that rely on the absence of federal rules as a shield expose themselves to litigation, reputational damage, and greenium collapse.

Indonesia leads sovereign green sukuk markets, having issued over USD 12 billion since 2018¹⁵. Despite comprehensive post-issuance reporting satisfying ICMA guidelines, the program illustrates critical verification failures:

• Context: Indonesia's green sukuk program aimed to fund renewable energy transition while meeting Islamic finance principles.

• Issues: Labelling Misalignment: Marketing emphasized renewable energy while 98% of proceeds supported water infrastructure¹⁶

• Impact Measurement Gaps: Allocation reporting without environmental outcome measurement despite energy projects delivering approximately 1 GW verified capacity¹⁷

• Additionality Uncertainty: Unclear whether funding enabled new projects or refinanced existing commitments against Indonesia's USD 285 billion climate financing gap¹⁸

• Governance Lesson: Process compliance without outcome verification exposes boards to liability when actual impacts fail to match marketed commitments.

Germany's approach demonstrates effective verification standards that preserve market confidence.

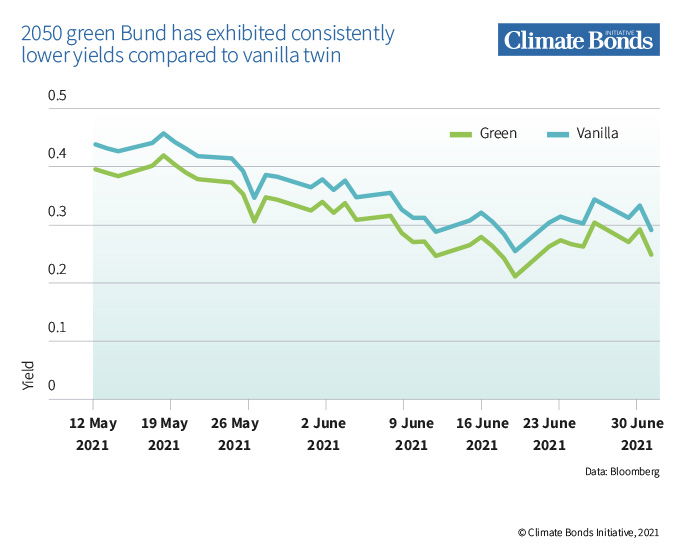

• Context: Germany issues paired "twin" bonds with identical credit profiles to provide transparent performance measurement.

• Success Factors: Independent verification of funded projects maintains consistent greenium effects; spreads stable at 0.5-2 basis points over four years¹⁹; Transparent methodology enables investor confidence

• Governance Lesson: Robust verification preserves market benefits and financing advantages while protecting directors from liability exposure.

Effective board oversight requires four critical components, grounded in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises framework requiring companies to "avoid causing or contributing to adverse impacts"²⁰:

At least one director should possess demonstrated expertise in environmental impact measurement, climate science, or sustainable finance, enabling meaningful evaluation rather than perfunctory approval.

Boards should mandate verification following OECD DAC criteria²¹, moving beyond issuer-commissioned second-party opinions to independent assessment using counterfactual baselines.

Real-time monitoring using satellite imagery, smart meters, and grid data enables continuous oversight. Examples include renewable energy grid connection verification and energy efficiency smart meter tracking.

Comprehensive contingency and exit planning must maintain environmental commitments even under financial pressure, treating environmental commitments as binding obligations rather than conditional promises.

Board oversight of verified impact reporting carries expanding personal liability exposure:

Directors face potential liability for misstating environmental performance in financial reports or investor communications. The Finch v. Surrey CC precedent requires directors to verify sustainability metrics with the same rigor applied to financial metrics.

Directors may breach fiduciary duties if they approve green investments that materially underperform environmental objectives without reasonable justification. The McVeigh v. REST and BT Pension Trustees v. Moore precedents establish this duty across multiple jurisdictions.

The COSO Enterprise Risk Management framework explicitly includes ESG risks²², requiring boards to integrate verified impact data into risk assessment and financial reporting.

Modern technology provides capability for boards to implement verification governance efficiently:

AI-powered systems monitor project performance against environmental targets and flag deviations requiring board attention, enabling proactive governance while reducing director time investment.

Distributed ledger technology enables immutable recording of environmental outcomes, creating audit trails satisfying legal compliance requirements. Major issuers are piloting blockchain-based verification systems²³.

Third-party data sources provide objective verification independent of management reporting, reducing information asymmetries and director liability exposure.

Enhanced verification requirements impose costs, but the financial case is compelling. Current greenium effects generate approximately USD 275–550 million annually in borrowing cost savings²⁴, while implementation costs are manageable. Industry data shows that external review costs typically range from USD 10,000 to USD 150,000 per issuance, with Climate Bonds Initiative certification fees at just 0.01 basis points of issue value²⁵. Even comprehensive third-party verification represents a fraction of typical bond issuance costs including credit ratings (3–5 basis points), legal fees, and underwriting²⁶.

Sources: Bloomberg, Dealogic, Eikon, Banque de France calculations.

Notes: Change in the premium on green bonds between 2018 and 2024. The greenium (curves) and 95% confidence intervals (shaded areas) are estimated using an econometric analysis.

• Context: A pension fund board approves a USD 500 million green bond allocation based on unverified renewable energy claims.

• Issue: When projects deliver water infrastructure instead, beneficiaries face a USD 25 million loss from greenium collapse and regulatory penalties.

• Governance Lesson: Under the McVeigh v. REST precedent, trustees face personal liability for inadequate due diligence on environmental claims. The USD 100,000 cost of independent verification becomes negligible compared to potential legal exposure exceeding USD 10 million in damages and legal fees.

The SEC's 2023 enforcement action against Vale S.A. demonstrates regulatory willingness to pursue ESG misrepresentation cases. Vale paid USD 55 million in penalties for misleading investors about dam safety — establishing clear precedent that environmental claims carry the same disclosure obligations as financial metrics. Directors approving unverified green bond claims face similar enforcement risk, with personal liability exposure under current D&O insurance exclusions for intentional misrepresentation.

Australia – Vanguard and Mercer Superannuation Fund (2024)

In March 2024, Australia's Federal Court ruled that Vanguard Investment Australia's claims about an "ethically conscious" fund were misleading. In June 2024, the same court found that trustees of the Mercer Superannuation Fund had made materially misleading representations regarding ESG credentials—and imposed a penalty of AUD 11.3 million (approximately USD 7.3 million) under securities law²⁶. While these cases targeted asset managers and trustees rather than directors per se, they exemplify how senior fiduciaries can be held personally accountable for ESG misrepresentation.

United Kingdom – ClientEarth vs. Shell Directors (2023)

In February 2023, environmental legal group ClientEarth filed a lawsuit against Shell's board of directors under the UK's Companies Act, alleging failure to implement a credible net-zero strategy. However, the case highlighted the complexity of director duties rather than establishing clear liability. The court emphasized that directors' primary fiduciary duty remains profit maximization for shareholders, leaving unresolved the fundamental tension between short-term profit maximization and long-term environmental stewardship where costs of CO2 emissions and pollution are externalized to society²⁷.

While this case did not establish director liability for climate strategy, it marked the first attempt to directly target individual directors over climate commitments, signalling the evolving landscape of potential personal accountability.

Greenium collapse would eliminate market benefits while potentially triggering broader sustainable finance corrections affecting USD 1.05 trillion in annual GSS+ issuance. Boards failing to implement adequate verification governance risk losing green financing benefits and facing regulatory sanctions, investor litigation, and reputational damage.

Before approving any green bond issuance, directors should ensure management can answer these five questions with verifiable evidence:

✓ Verification Independence

"Who will independently verify our environmental outcomes, and are they accredited under relevant frameworks (ESMA, OECD DAC criteria)?"

Red Flag: Management proposes using issuer-commissioned second-party opinions without independent oversight.

✓ Measurable Outcomes

"What specific, quantifiable environmental outcomes will we deliver, and how will we measure additionality against counterfactual baselines?"

Red Flag: Vague commitments to "support renewable energy" without GW capacity targets, timeline commitments, or baseline comparisons.

✓ Legal Exposure Assessment

"What is our potential liability exposure if actual environmental outcomes fail to match marketed commitments, and have we obtained appropriate D&O coverage?"

Red Flag: Legal counsel has not reviewed green bond documentation for misrepresentation risks under current ESG litigation precedents.

✓ Technology-Enhanced Monitoring

"Do we have real-time monitoring systems (satellite imagery, smart meters, grid data) providing objective performance data independent of management reporting?"

Red Flag: Reliance solely on self-reported project performance without third-party data verification.

✓ Contingency Planning

"If projects underperform or face technical difficulties, how will we maintain environmental commitments while protecting greenium benefits?"

Red Flag: No written contingency plans for project failures, policy reversals, or climate-related disruptions affecting financed projects.

Directors who cannot obtain satisfactory answers to these five questions should defer approval until adequate verification infrastructure is established.

The convergence of legal precedent, regulatory momentum, and governance principles creates an unmistakable mandate for enhanced green bond governance. The transformation from voluntary reporting to mandatory verification reflects a fundamental shift in corporate accountability — one that boards can no longer ignore or delegate.

In the United States, this imperative is amplified by regulatory fragmentation. At the federal level, the SEC’s 2024 climate disclosure rules — which would have embedded independent assurance into corporate reporting — are now stalled, following litigation and the Commission’s decision not to defend them. Yet this retreat does not shield directors from liability: the SEC continues to prosecute ESG misstatements as securities fraud, as seen in SEC v. Vale S.A. At the state level, California has moved decisively with SB 253 and SB 261, mandating third-party assurance of greenhouse gas disclosures and imposing meaningful penalties for non-compliance. Federal inaction therefore increases rather than reduces governance risk, forcing boards to anticipate overlapping state, investor, and global requirements without waiting for Washington to set the standard.

By contrast, the European Union and other jurisdictions are embedding verification as a norm through the EU Green Bond Standard, CSRD, and related frameworks. For globally active issuers, this asymmetry magnifies reputational and legal risk: investors expect verification as a baseline, regardless of jurisdictional divergence.

The evidence is overwhelming. Legal precedents from McVeigh v. REST to Finch v. Surrey CC establish director liability for inadequate environmental verification. State legislation in the U.S. is imposing mandatory assurance despite federal retreat. Market forces are equally clear: investors demand outcome proof, not process compliance.

The message for boards is unambiguous: federal gaps do not reduce responsibility; they heighten it. Verified impact reporting is now a governance duty owed to investors, regulators, and stakeholders alike. Directors who embrace this responsibility will preserve financing advantages, strengthen trust, and insulate themselves from the escalating risks of misrepresentation. Those who delay face an increasingly stark choice: proactive governance or reactive enforcement in a fragmented regulatory landscape.

The window for voluntary adoption is closing. Verified impact reporting is not a future consideration; it is an immediate priority requiring decisive board action. Those who act now will lead the transformation toward sustainable finance integrity. Those who hesitate risk explaining not just to investors, but to regulators, why their green bonds delivered promises instead of proof.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Sustainability needs facts, not just promises. illuminem’s Data Hub™ gives you transparent emissions data, corporate climate targets, and performance benchmarks for thousands of companies worldwide.

¹ Conservation Finance Network (2020). "Green Bond Certification Costs"; Climate Bonds Initiative Certification Programme.

² Climate Bonds Initiative (2025). State of the Market 2024: Green Bonds & Sustainable Finance. ² Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 on sustainability‐related disclosures in the financial services sector. ² SEC Proposed Rule: Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures (March 2022).

³ Bloomberg New Energy Finance (2024). Green Bond Pricing Analysis.

⁴ Regulation (EU) 2023/2631 on European Green Bonds.

⁵ Monetary Authority of Singapore (2024). Green Finance Taxonomy; HM Treasury (2024). UK Green Taxonomy.

⁶ ICMA (2024). Green Bond Principles: Voluntary Process Guidelines.

⁷ BlackRock (2024). Investment Stewardship Annual Report.

⁸ McVeigh v. Retail Employees Superannuation Trust (2020), Federal Court of Australia Settlement.

⁹ Milieudefensie v. Royal Dutch Shell (2021), District Court of The Hague.

¹⁰ R (Finch) v. Surrey County Council [2024] UKSC 50.

¹¹ SEC v. Vale S.A. (2023), U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York. ¹² BT Pension Trustees v. Moore [2023] EWCA Civ 875.

¹³ Ferran, Eilís (2024). "ESG Fiduciary Duty Evolution: Post-Issuance Accountability," Oxford Business Law Blog.

¹⁴ OECD DAC (2019). Better Criteria for Better Evaluation.

¹⁵ DDCAP (2024). Sovereign Green Sukuk Market Analysis.

¹⁶ Ministry of Finance Indonesia (2023). Green Sukuk Allocation and Impact Report. ¹⁷ NS Energy Business (2024); Star Energy Geothermal (2020).

¹⁸ Brookings Institution (2024). Funding Climate Agenda in Indonesia.

¹⁹ Deutsche Finanzagentur (2024). German Federal Green Security Reports.

²⁰ OECD (2023). OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct. ²¹ OECD DAC (2019). Better Criteria for Better Evaluation.

²² COSO (2023). Enterprise Risk Management: Integrating with Strategy and Performance.

²³ World Bank (2024). "Blockchain Applications in Green Bond Verification."

²⁴ Bloomberg New Energy Finance (2024). Green Bond Market Analysis.

²⁷ MLT Aikins (2023). "ClientEarth vs. Shell Directors: Personal Liability for Climate Strategy."

Jane Marsh

Wellbeing · Services

illuminem briefings

Sustainable Business · Services

Riad Meddeb

Consumers Green Tech · Services

Irish Independent

Sustainable Business · Carbon Removal

The Wall Street Journal

Sustainable Business · Pollution

ESG News

Carbon Market · Carbon