Tackling root causes: reversing the biodiversity crisis requires rethinking the global economic model

· 9 min read

The air we breathe. The water we drink. The food we eat. They all depend on the Earth’s biodiversity which provides us with the foundational conditions for life on Earth. Yet, the future survival of human beings is under threat amid the unprecedented rates of global biodiversity loss. The fact that among the nine planetary boundaries, biodiversity is among those that have been driven the furthest beyond their safe operating space indicates the severity of the crisis. Indeed, constituting one of the core challenges of the so-called triple planetary crisis, the depletion of biodiversity has reached such an alarming state that it is arguably initiating a sixth mass extinction, the last of which happened 65 million years ago and resulted in the extermination of dinosaurs from Earth.

Biodiversity encompasses the variety of living species across the Earth’s terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems, including plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi, as well as the complex ecosystems that these inhabit. Such ecosystems provide vital benefits in the form of ecosystem services, which provide us with the fundamental conditions that support multiple aspects of human existence and well-being. Such ecosystem services include carbon sequestration by plants, the filtering of freshwater, the pollination of crops by bees and other insects, and nutrient cycling in soils, among a vast range of other benefits.

However, the aggravating global biodiversity crisis impacts the provision of these vital ecosystem services. The current extinction of species is estimated at up to a thousand times the natural rate and is projected to lead to the loss of more than a million species in the coming decade. Already today the scenario is dire - since 1970, the size of worldwide animal populations has declined on average by 69%, with 83% of the wild mammal population already having been lost. Such loss occurs across different ecosystems with 40% of terrestrial, 30% of freshwater, and 35% of marine animal species facing extinction.

The depletion of biodiversity together with that of its ecosystem services has important societal as well as economic implications. The decline in the number of pollinators, for instance, threatens global food security given that 75% of food crops depend on them. Beyond that, biodiversity loss directly affects human health treatment as half of the global population depends on natural medicines and around 70% of cancer-treating drugs are obtained from natural or nature-inspired products.

The urgency of addressing the crisis derives, beyond its societal impacts, from the central role that biodiversity plays in the global economy. The total economic value of ecosystem services is estimated at more than one and a half times the size of the global gross domestic product (GDP). At the same time, the present rates of biodiversity loss indicate that the global economy may be losing over US$5 trillion worth of ecosystem services per year.

While extinctions are a part of evolution and the past five mass extinctions were caused by natural climatic and environmental changes, the present one is undoubtedly extensively driven by human activities and, more specifically, the linear production and consumption model which characterises global economic activities. The linear economy is commonly named a ‘throughput’ or a ‘take-make-waste’ economy as it takes virgin resources from the natural environment, makes these into goods, and disposes of them as waste when they are no longer used, needed, or wanted. The linear economy is founded upon the prospect of infinite material and economic growth which, to be realised, depends on the continuous extraction of virgin natural resources and their processing into material goods.

However, the natural environment is not fit to support the illusion of infinite material growth. The present rate of natural resource extraction exceeds the rate at which the environment can regenerate them. Contemporary production and consumption patterns are thus responsible for 90% of biodiversity loss, a number which is expected to double by 2060 within a linear economy that, left unchanged, is set to perpetuate a lock-in of continued biodiversity loss.

Besides the overexploitation of natural resources, current economic activities depend on extensive land and energy use and generate large amounts of waste and pollution. Taken together, these activity patterns place immense pressure on natural ecosystems. They spur what the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has defined as the five core anthropogenic drivers of the biodiversity crisis, namely (1) land and sea use change, (2) overexploitation, (3) climate change, (4) pollution, and (5) invasive alien species.

The key to tackling the biodiversity crisis lies, therefore, in addressing the linear model upon which the current global economic system is founded. Given the systemic nature of the challenge, merely focusing on incremental adjustments to a perpetuated linear economy will not solve the root cause of the crisis at a global scale. To solve it, we require transformative systems-wide change.

This means, firstly, that we must question the dominant structures of the linear economic model and fundamentally rethink how we source, produce, and consume resources and products. Secondly, it means that, although of central importance, efforts to conserve what is left of biodiversity alone will not suffice to reverse the magnitude of the damage already caused and to ensure the continued prosperity of a growing world population. Therefore, rethinking the current economic model requires shifting to an approach that extends beyond mere sustainability to one that is based on a regenerative paradigm. Such a paradigm focuses on restoring natural ecosystems to a state in which they are given space to thrive and remain resilient to changes over time.

It is in this context that the circular economy presents itself as a valuable framework for rethinking the global economic model and as a key to tackling the root cause of the biodiversity crisis. A circular economy is an alternative economic model that recognises the impossibility of infinite material growth on a finite planet and strives to reconcile and foster long-term environmental, societal, and economic prosperity. It seeks to do so by decoupling economic and human development from natural resource extraction and its related impacts on natural ecosystems.

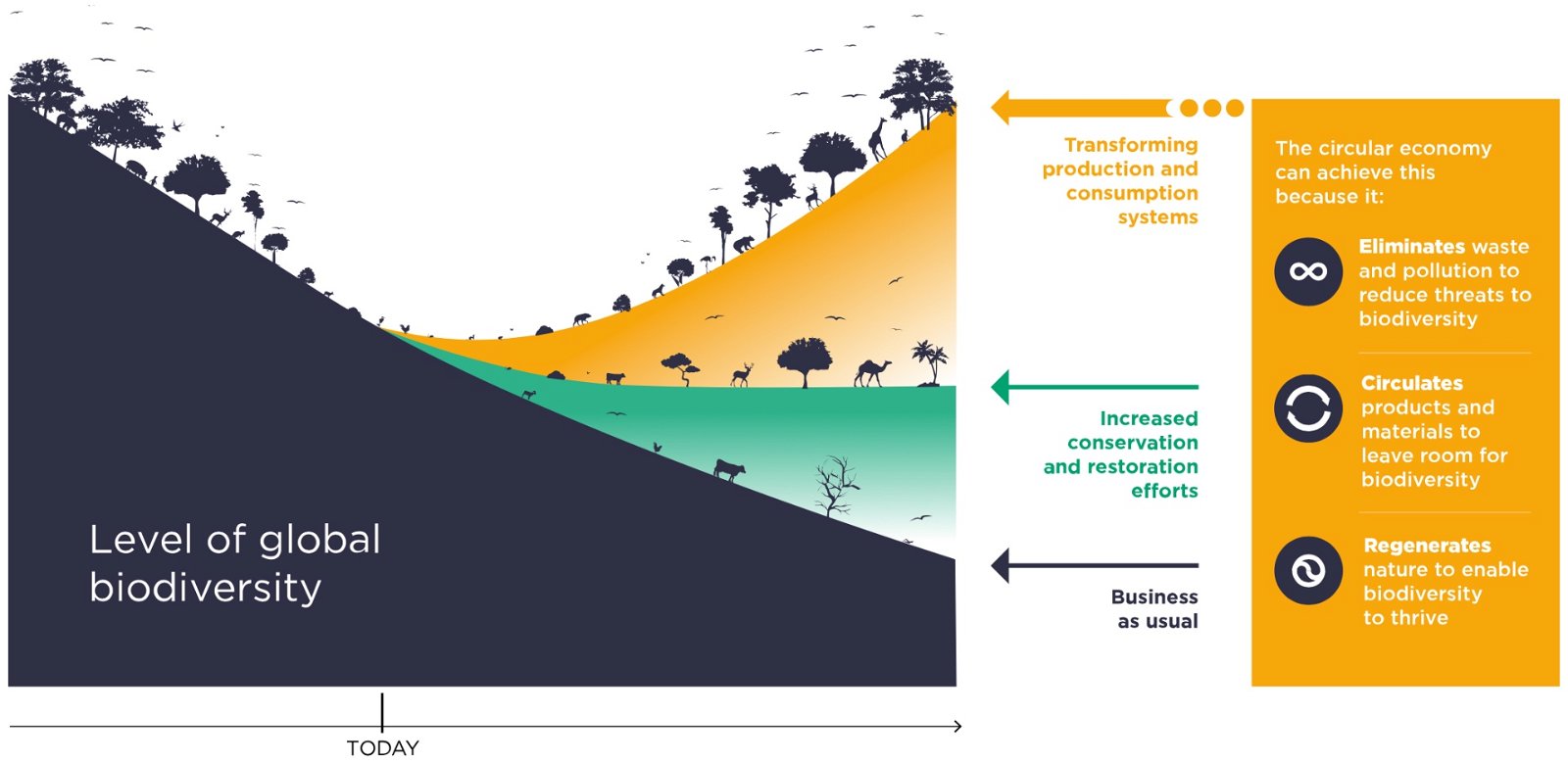

Under that objective, the circular economy is characterised by three fundamental principles. By shifting to a closed-loop economic model, it seeks to (1) eliminate waste and pollution by (2) keeping products and materials in circulation at their highest value within the economy, and, thereby, (3) regenerate nature. That way, by more productively using products and materials within the economic system, a circular economy drastically reduces the demand for virgin natural resources and addresses thereby the core root cause of the biodiversity crisis. Beyond rethinking how we source, produce, and consume resources and products, a circular economy also adopts practices and activities that seek to actively regenerate nature. Examples include approaches such as agroforestry, mixed cropping, and regenerative ocean farming in the food sector and regenerative fiber cultivation in the textiles sector, as well as practices across other economic sectors.

The figure below illustrates how a circular economy through the application of its three fundamental principles can have a biodiversity-positive impact beyond that which conservation and restoration efforts alone can have in merely halting further biodiversity loss.

Recognising the fundamental role that biodiversity plays for the economy, society and the wider environment, the global policy agenda has recently made important strides in including the biodiversity crisis at the centre of environmental commitments. Recent years have witnessed the publication of different policies and regulations specifically addressing the biodiversity crisis and demanding actions by governments and corporations to tackle it.

Being the first global agreement of its kind, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was passed at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in December 2022. The agreement builds a pathway towards the global vision of a world living in harmony with nature by 2050 by expanding the area of globally protected land and oceans, restoring depleted ecosystems, and mobilising funds for biodiversity-related efforts. Other recent regulations and treaties, including the Treaty of the High Seas, the European Union (EU) Biodiversity Strategy 2030, and the EU Nature Restoration Law, are further contributing to the growing commitments to tackle biodiversity loss.

While such commitments are increasing efforts to tackle the biodiversity crisis, they are at risk of not being met under current trajectories of continued biodiversity loss. This indicates the importance of coupling biodiversity policies and regulations with transformative change in activities to tackle the biodiversity crisis at a global scale effectively.

While several researchers argue that present biodiversity loss is leading to a sixth mass extinction, data indicates that we are yet far from that point. The extinction of species can take different trajectories in the coming decades and centuries, and it is up to us to carve out which path it will take. The power is in our hands to rethink the current economic model which lies at the root cause of the crisis. The circular economy may be the necessary key to initiating that change and supporting the achievement of the global biodiversity policy agenda.

Notwithstanding, it is also important to recognise that the circular economy is not a panacea to either the multifaceted challenges of the current linear economic model or to solve the global biodiversity crisis on its own. An integrated set of approaches is required that pursues a circular economy in complement to nature conservation and restoration activities and other economic frameworks that together create the enabling conditions for sustainable development. In addition, while the circular economy is receiving increasing attention as a pathway to tackling the biodiversity crisis, its benefits to actively regenerate biodiversity remain yet underexplored and poorly quantified. While research has initiated the discourse on the potential of the circular economy for a nature-positive future, further research on the topic is called for.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Gokul Shekar

Effects · Climate Change

Michael Wright

Agriculture · Environmental Sustainability

Simon Heppner

Effects · Climate Change

The Guardian

Biodiversity · Nature

The Guardian

Pollution · Nature

CGTN

Renewables · Nature