Reconciling Sovereign Debt and Natural Capital

· 3 min read

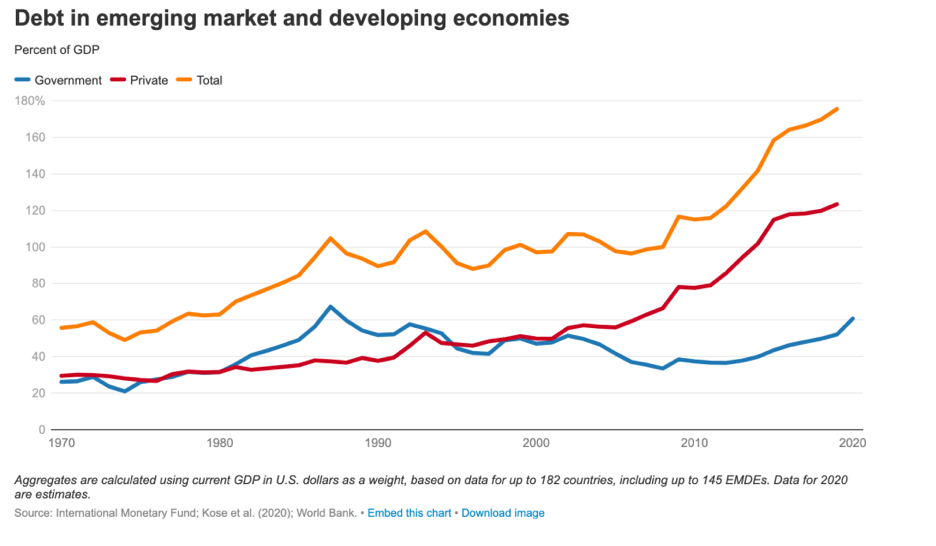

xFalls in FDI and trade imposed by lockdowns, concurrent with the need to manage unstable health and economic systems, has plunged low-income countries (LICs) into a debt spiral. Globally, sovereign debt has increased by around $10 trillion. Not to say that it was stable before the pandemic; in fact, the IMF signalled half of LICs were in debt distress in January 2020. But the emergency fiscal stimulus packages being deployed globally show countries are going beyond rationales of debt vulnerability, instead investing in much needed social infrastructure. Mass sovereign debt restructuring is around the corner.

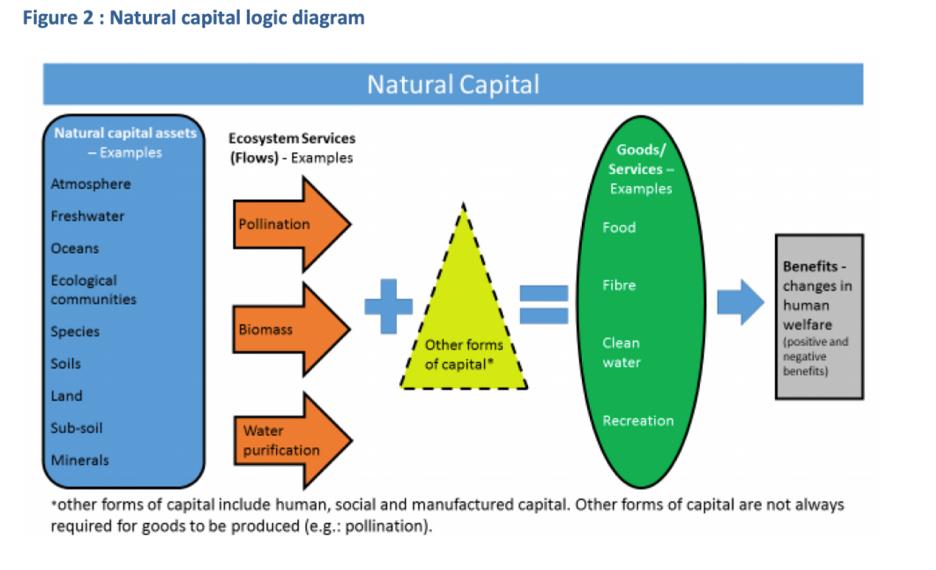

It is imperative that the recovery from Covid-19 be compatible with climate and nature. That’s why a growing number of voices in policy and finance have called for approaches that endorse sustainability-oriented debt instruments. With $281 trillion total active sovereign debt globally, this can be a great avenue for advancing natural capital principles. Natural capital represents the value our economies derive from nature, and on which they depend. As climate change and environmental degradation intensify, we lose natural capital, with knock-on effects on financial and economic stability.

More and more people now recognise the interoperability between economic and ecological systems, the fact that agricultural output needs pollinators, or that our cities depend on the provision of natural resources and ecosystem services. LICs are home to large portions of the world’s critical biodiversity. Neglecting its conservation will have severe consequences for these countries’ wealth, but also global repercussions. In the current context, debt restructuring appears as a means of safeguarding natural capital. First introduced by conservationist Thomas Lovejoy in 1984, debt-for-nature swaps have never reached sufficient sums, due to the inherent challenges of debt restructuring negotiations. Thus, new frameworks should be envisaged.

For nature to have its rightful place in debt portfolios, incentives must be provided on both sides. Attaching green-performance-linked interest rates to securities or local currency swaps would better enable sovereigns to protect their natural assets. For creditors, natural capital could serve as a condition for a debtor’s creditworthiness, informing their investment decisions. According to the Finance for Biodiversity Initiative, the priority is twofold. First, multilateral financial institutions must support a common framework for green sovereign debt relief. Second, investors need the guarantee that green debt serves their needs, can be easily priced, and provides adequate liquidity.

One idea put forward is the creation of a designated fund connecting investors with SDG-related market debt. Refinancing would be geared towards nature conservation projects or simply infrastructure development respective of natural capital. Green bonds would then be phased in progressively. The Green Economy Coalition notes that this approach does not erect barriers to sectors like health or education. In fact, nature conservation can go hand-in-hand with systemic SDG pursuit.

Gathering political momentum around this issue will be of utmost important in 2022, as a post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework is established at the CBD15. Multilateral development banks in particular will seek to converge private capital with their own sustainable bonds. States will need to endorse such a reward-based debt framework, with precursors able to draw from the experience of green bond issuance; France, for example, has so far issued $40.7bn worth of green sovereign bonds. The momentum among industrialised countries must diffuse across the lower-income bracket, so as to avoid yet another fossil-intensive round of debt restructuring.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Biodiversity · Sustainable Lifestyle

Aaron Bruckbauer

Pollution · Greenwashing

Jesse Scott

Carbon Market · Carbon Regulations

The Guardian

Power Grid · Climate Change

NPR

Climate Change · Public Governance

BBC

Biodiversity · Climate Change