Rebound effect: the whiplash of innovation

· 7 min read

Do you know that Germany has invested 340 billion euros in home insulation over the last ten years to save energy, and has saved almost nothing? Because houses were well insulated, people spent less money for the same amount of heating, which led Germans to heat their homes to 22°C instead of 20°C. This kind of behaviour may seem silly to you, especially considering the amount of money Germany spent and the lack of results. Yet, it is incredibly common and known as the 'rebound effect'.

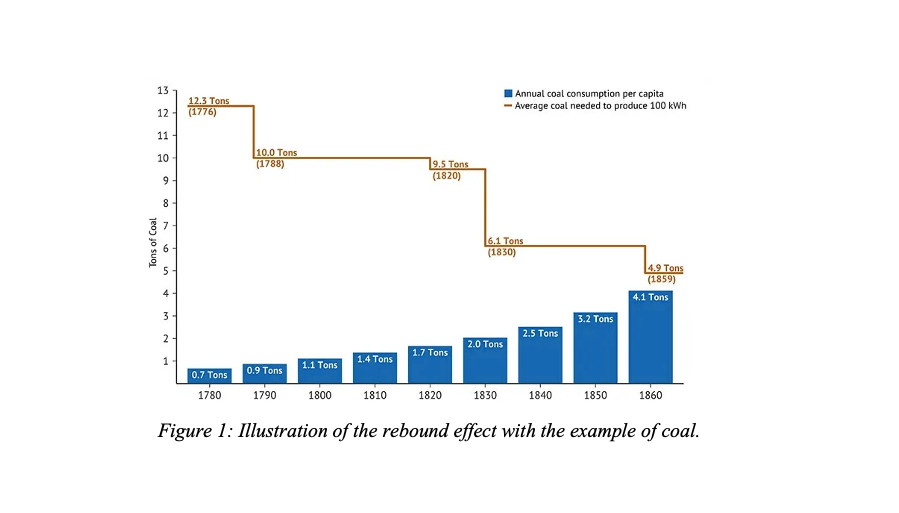

Sir Jevons was a 19th-century British economist. He studied the subject of coal, in particular the links between the exploitation of this resource and the United Kingdom's domination of the rest of the world at that time. Noting an exponential growth in the consumption of this resource, he was concerned about the possible consequences for the country once the peak had passed. Therefore, Jevons looked for ways to reduce coal consumption, including more economical use and more efficient machinery.

He then noticed what would later become known as Jevons' paradox: the increase in the efficiency of machines, thanks in particular to the invention of the steam engine by James Watt, led to an increase in coal consumption [Figure 1].

The paradox is that if a machine consumes less coal for the same purpose, one would expect total coal consumption to decrease. This was without considering the adaptation of human behaviour: for the same production, the machine certainly costs less coal. But it allows for more diverse uses, and one can also afford to use more for the same amount of coal. This explains the widespread use of coal in the manufacturing industry, which has led to an increase in consumption. In 1980, Khazzoom called this paradox the "rebound effect", particularly by studying this phenomenon in the energy consumption of household appliances. He describes the rebound effect as the fact that ‘the estimates of energy savings predicted to result from these mandated standards are derived mechanically’.

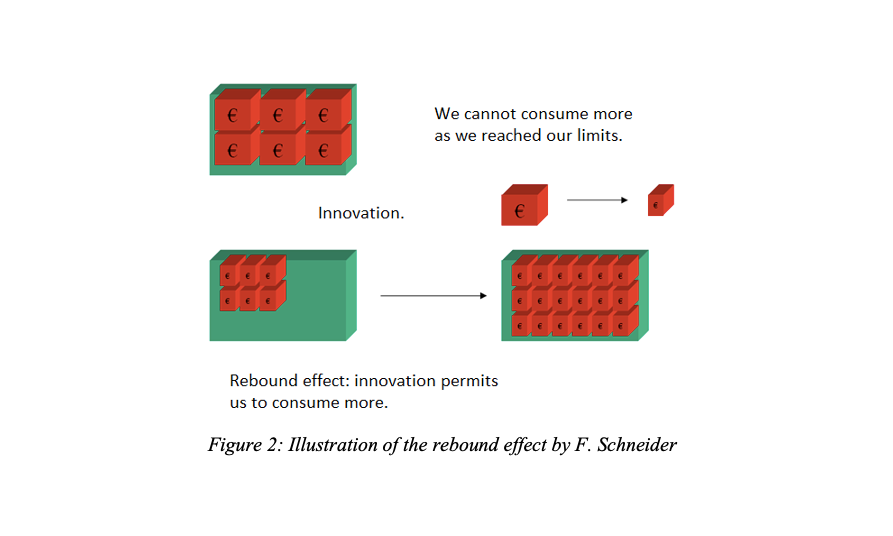

However, Jevons' paradox is a special case of the rebound effect. This term ‘rebound effect’ characterises only the increased consumption of a technology in relation to reductions in the limits to its use. This means that the actual savings from reducing a limit to a technology, whether technical, financial, or ecological - often all three - are less than theoretically possible. This effect is often quantified by the following formula:

The term ‘Jevons’ paradox’ or ‘backfire’ only characterises a rebound that would exceed 100%, making the situation worse than if no technological improvements in efficiency had taken place in the first place, when the potential gains are more than offset by the negative effects.

Since then, some people, especially economists, have looked into this phenomenon. François Schneider defines the rebound effect as an increase in consumption linked to the reduction of financial, temporal, physical, social, etc. limits to the use of a technology [Figure 2].

The rebound effect highlighted by Jevons was due to the removal of a technological and financial barrier (the cost of coal). Most rebound effects are due to this type of barrier, but temporal and ecological barriers must also be considered. Furthermore, the rebound effect is extremely common in two areas in particular: energy and digital.

In the field of energy, the ADEME (Agency for the Environment and Energy Management) has estimated that in France, between 1982 and 2012, while final energy intensity had decreased by 30%, final energy consumption had increased by 15%, from 134 Mtoe to 154 Mtoe. Indeed, as energy was cheaper, the French consumed more of it, as was the case for coal in Jevons' time.

For digital technology, the improved energy efficiency of transmission networks has led to an explosion in data traffic. This is the case with 4G and then 5G: it takes less time and less energy to download a given amount of data, so users are loading much more data than before. The result is an explosion in energy consumption and GHG emissions from the digital sector, which already accounts for almost 4% of global GHG emissions.

Thus, technological innovations to relieve human pressure on the environment may even turn out to be false good ideas.

In a nutshell, what is important to note is that the rebound effect is likely to occur wherever a barrier is removed. Indeed, Jevons and Schneider have shown that ecological innovation in a growth economy inexorably leads to a rebound effect. According to them, to be effective in reducing environmental impacts, innovation must take place in a context of economic contraction and frugality in consumption. Indeed, technological innovations are multiplying in an attempt to respond to climate and environmental challenges.

However, what matters is not the energy, material, or emissions per element, but the total energy, material, or emissions. Therefore, if the rebound effect is not considered, the effects are likely to be reduced, cancelled out, or they will even worsen the situation.

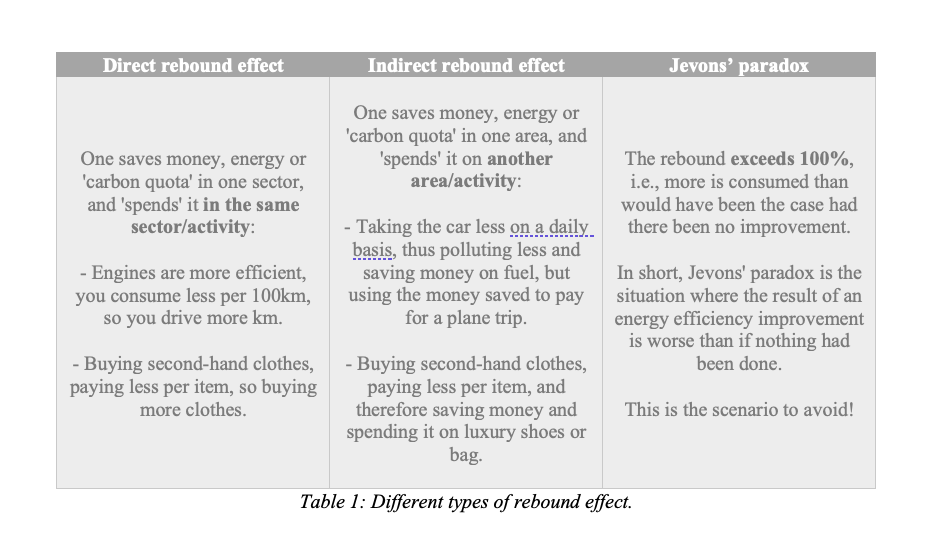

To summarise and clarify the situation a little, it is essential to have in mind the different rebound effects. Indeed, one of the difficulties of the rebound effect is its multifactorial and sometimes even hidden character.

There are two main types of rebound effect, plus the Jevons paradox [Table 1].

We can thus see how difficult it can be to quantify the rebound effect, especially when the effects are indirect: "The concept is simple to understand, much harder to demonstrate with numbers".Unfortunately, when it is difficult to quantify, it is not taken into account in projects and policies, including in scientific articles such as the IPCC or the IEA. Hence the emergency to raise awareness about this topic.

It is certainly difficult to put in place solutions to reduce something that we find hard to quantify. However, it is important to know that in some cases, particularly in the energy field, quantifications are present and precise. Moreover, we must not forget that the rebound effect is due to the human factor. Thus, encouraging people to change their behaviour can help reduce the rebound effect.

This can be done by raising awareness of ecological issues: making people aware of the rebound effect makes it easier to avoid it. The responsible fashion sector has conducted several massive awareness campaigns on this subject.

The Patagonia brand has a very strong ethical and environmental policy. It also ran an advertising campaign during Black Friday calling on consumers not to buy. ‘Don't buy this jacket’ encouraged consumers not to buy what they did not need.

Indeed, the brand declared: ‘It's time for us as a company to address the issue of consumerism’, thus stirring up the fashion world by being strongly relayed on social networks.

In the same idea, the French brand Loom, founded in 2016, has a business model based on producing less but better. The clothes are indeed designed to last, and the customer service takes returns after the first year of use to ensure that the quality of the clothes is not deteriorated. The brand also studied the rebound effect (of new clothes) and thus concluded that it was better to reduce emissions at source by reducing production, and that frugality was a priority.

Finally, initiatives are flourishing to raise public awareness of consumption and frugality. This is the case, for example, with Zero Waste Scotland and Edinburgh Science, which have organised awareness-raising workshops in George Square in Glasgow. Information was provided on the environmental impact of fashion, but also on solutions to be implemented, such as sewing, repairing, but above all questioning one's needs.

While solutions exist and are increasingly being found on an individual scale, reflection on a collective scale is much more profound and complex, but not impossible, as it requires us to question the entire consumption model on which our societies are based.

The rebound effect arises when financial, temporal, physical, social, etc. limits to the use of technology are reduced. The consequences are an increase in resource consumption and CO2 emissions, sometimes greater than if no reduction had been allowed in the first place.

It is therefore understandable that this can be a problem in the fight for environmental protection: innovations may improve existing uses but increase the pressures of behavioural change. This is what has happened with electronic equipment, the use of fuel-efficient cars and the renovation of buildings.

This effect appears when we have understood the solutions but not the problem. Thus, environmental solutions in a growth economy will almost inevitably lead to rebound effects. So, what we need to do to avoid it and really reduce our pressures on the environment is to question our consumption at the root. What do we need and what do we do with it? This cannot be done without a massive awareness of the scale of the environmental challenges.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Corporate Governance · Adaptation

illuminem briefings

Sustainable Finance · ESG

illuminem

Adaptation · Biodiversity

CBC News

Climate Change · Biodiversity

Human Rights Watch

Adaptation · Environmental Rights

The Wall Street Journal

Public Governance · Sustainable Finance