Rare earths, China and market dominance

Unsplash

Unsplash Unsplash

Unsplash· 6 min read

When I pick up a smartphone or drive a car, I am aware that its existence depends on extremely complex supply chains. But I wasn’t aware until recently of the increasingly pervasive importance in many technologies (sustainable or otherwise) of the so-called “rare earths”. Awareness has of course recently risen sharply since China’s decision in April to impose export licensing on many of them. Resulting “rare earth” supply disruption is now threatening output of electric cars, amongst other products, raising major questions about market functioning. So, what I want to explore in this newsletter is:

• What rare earths are and where they are used

• China’s production dominance and export licensing

• Why developing other rare earth sources will take time

Rare earths are a set of 17 chemically similar elements which may be found in nature in combination with other substances. Their names may not be familiar to you, but they are increasingly important to how we live. Rare earths are used both in leading industries driving the sustainable transition (e.g. renewable energy, electric vehicles) and many more traditional sectors (e.g. defence, electronics).

Rare earth uses in vehicles, for example, include magnets for electric motors (Dysprosium, Neodymium, Terbium, Praseodymium and Samarium), fuel cells (Terbium) and batteries (Neodymium, Lanthanum and Cerium). Rare earth magnets also find their way into wind turbines and rare earths are used in energy-efficient lighting. There are many other uses for rare earths in these and other areas: the problem is that they can be difficult to substitute with other minerals or technologies.

Rare earths were not a focus of the US administration’s “Liberation Day” tariffs announced at the start of April. But China, the world’s major producer of rare earths, was quick to see an opportunity for policy leverage when it responded to US tariffs. It announced restrictions on Chinese exports of seven rare earths and of high-performance rare earth magnets. Foreign companies seeking to export these rare earths from China must now apply for licences, a process that takes time and, potentially, the disclosure of sensitive material on these companies’ activities.

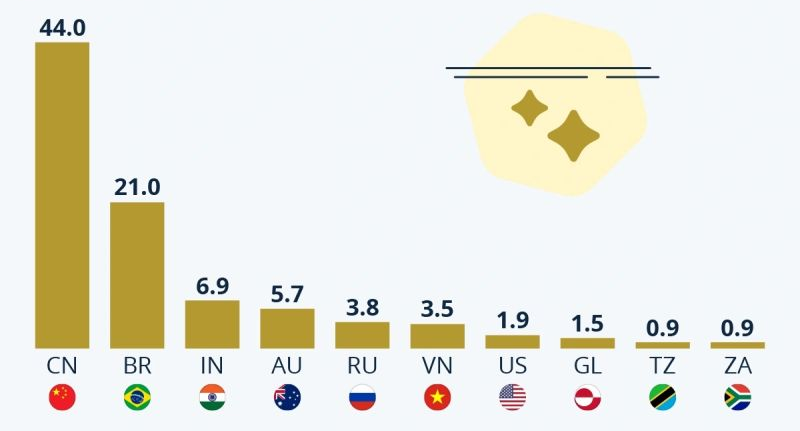

China would appear to be in a strong position here. It accounts for almost 70% of global rare earths production[i] and, as importantly, perhaps 90% of rare earths processing which can be difficult and capital intensive. (Rare earths tend to be thinly spread as trace impurities, so getting them to a useful level of purity can require processing of vast amounts of ore and result in major environmental damage.) China also has the world’s biggest rare earths mine, Bayan Obo in Inner Mongolia. Some rare earths (e.g. dysprosium) have no large rival producers outside China. In short, there is no hope that non-Chinese production can immediately make good any shortfall in global rare earths extraction or processing.

China’s decision to impose export licences has certainly accelerated discussions around the issue. President Trump has claimed a deal with President Xi on the issue, with some concessions to China: late last week, China’s Commerce Ministry, appeared to confirm that it would now “review and approve eligible export applications”. Meanwhile, EU businesses have been lobbying China for a special “fast track” channel for licences. India (which has an increasingly important autos sector) has despatched a business group to Beijing. The impact of export licensing is already affecting auto production around the world, with output of some individual models suspended.

I think that a settlement will be found to the rare earths issue: there are many risks for China in pursuing this approach too aggressively. But, even if China rows back quickly on export licensing, the threat of its future deployment remains. So how can rare earth users outside China protect themselves against future supply disruption?

The obvious response (by corporates and governments) would be to diversify sources of supply of rare earths. Possible alternative sources do exist: rare earth projects are at various stages of development in Greenland, Canada, the U.S., Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa and other countries. But developing new extractive facilities and the associated processing will take time and large amounts of money.

The big question is whether the necessary investment will really happen. There is an interesting recent article by executive director of the International Energy Agency (IEA), Fatih Birol, where he looks at diversification in critical minerals production, markets and possible causes of market failure.[ii] As he points out, a range of technologies in energy, electronics and aerospace depend on the same critical minerals (including rare earths) and have highly interconnected supply chains. At the IEA, he says, a “golden rule” for energy security involves diversification (of both energy source and suppliers). But, in the case of these critical minerals (copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt and graphite, as well as rare earths), the reverse is true. The average market share of the top three producers has risen to 90%, with China the leading refiner of 19 out of 20 such minerals. We are facing a situation of market concentration, not diversification.

Mr Birol’s argument is that, with markets generally well supplied with such minerals in the recent past, prices have been low and this has reduced the incentive for investment outside China, despite strong projected growth in the use of such minerals over the next decade. According to him, projects elsewhere also face capital costs that are around 50% higher than those in China and other incumbent refiners. Long-lead times for most projects can make the problem of investment even more acute.

This is his stark conclusion: “left to their own devices, markets will not deliver the level of diversification that would significantly reduce supply security risks”. To rectify matters, “policy support and international partnerships are essential” and “tools such as price support mechanisms, demand guarantees and incentives tied to high environmental and social standards could unlock new sources of supply”.

I hope so – but such measures will take a long time to put in place, and in the interim, I suspect that “beggar my neighbour” competition for supply could intensify.

China is fortunate to be blessed by large supplies of rare earths and has worked hard to develop them. Its combination of extensive rare earth supply and relevant industrial muscle (for example in renewable energy technologies) will continue to give it a unique position in related global trade. I hope very much that rare earths production can be diversified, with new reserves discovered and developed elsewhere, but I fear the process will take time.

This article is also published on the author's blog. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Purva Jain

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

illuminem briefings

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

illuminem briefings

Energy Transition · Public Governance

Deutsche Welle

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

Climate Home News

Energy Transition · Public Governance

Politico

Energy Transition · Public Governance