· 6 min read

Introduction

It was a happy 90th birthday for LEGO (see sustainability performance).

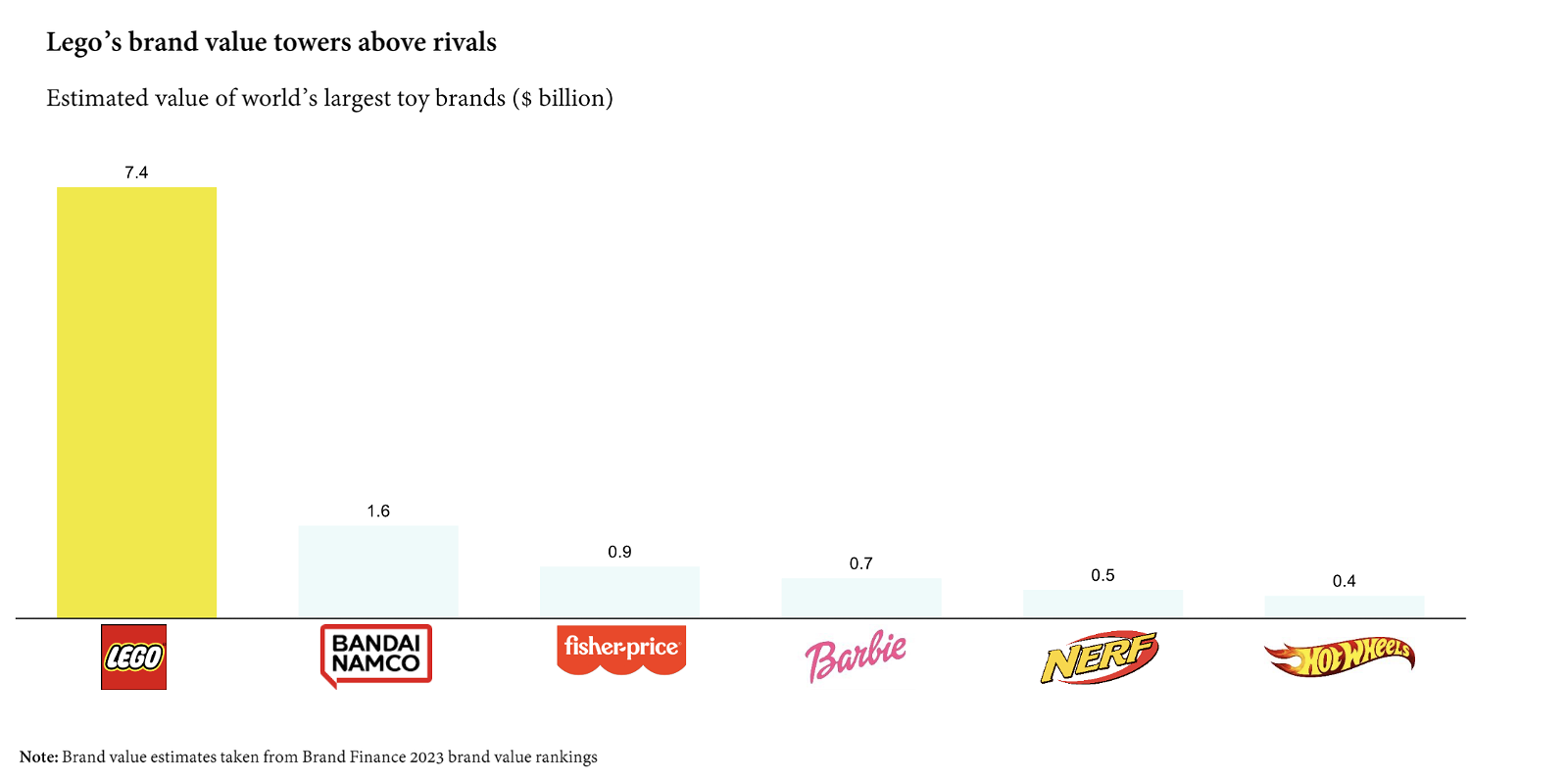

During 2022, the year of the milestone anniversary, the toymaker grew revenues by 17 percent, totalling over $9 billion. For the ninth consecutive year, it ranked as the most valuable toy brand in the world, its estimated brand worth of $7.4 billion dwarfing the $1.6 billion of its closest rival, Bandai Namco (owner of the PAC-MAN franchise).

But LEGO, a company born in a village in Denmark in the 20th century, now faces a very 21st century problem: its empire, quite literally, is built on plastic.

And despite ambitious pledges, there is little to show for LEGO’s sustainability efforts. A recent high-profile backtrack highlights the obstacles that stand in the way of ‘sustainable’ LEGO.

Its top line is not suffering so far, but the LEGO sustainability story is a cautionary tale for businesses and customers alike in the move away from plastic.

Locked in a petrochemical playground

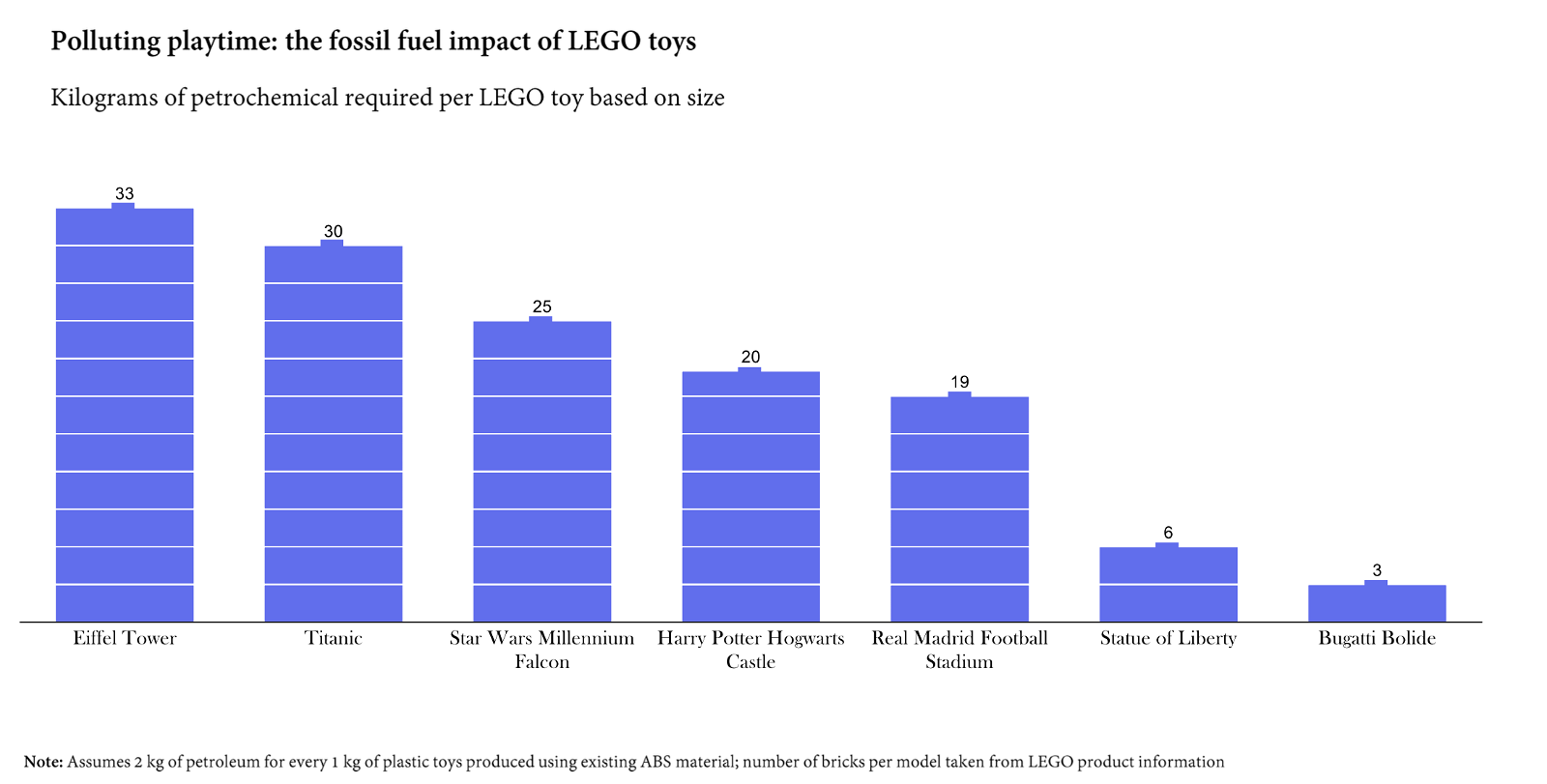

Every tonne of LEGO produced uses approximately 2 tonnes of petrochemicals in the manufacturing process. LEGO makes approximately 60 billion bricks per year, indicating that some of LEGO’s largest sets would require over 30 kilograms of petrochemical equivalent to produce.

LEGO’s environmental issues with plastics go back a long way. A ship accident off the UK coast in 1997 led to 62 containers (some with nearly 5 million Lego pieces) falling into the sea. Some pieces are still being discovered over 25 years on.

This was why the 2021 announcement of the ‘Bottles to bricks’ initiative was interpreted by many as a genuine signal of intent for LEGO to translate commercial activities into sustainability leadership. Under ‘Bottles to bricks’, the company stated its target to mass-manufacture its blocks from end-of-life materials – mainly plastic bottles.

The move was widely praised in the mainstream media: a Reuters headline declared that “Lego finds the right fit with recycled plastic”.

But the praise was premature. In September 2023, LEGO confirmed that it was abandoning the project, with the proposed alternative material – recycled PET – estimated to increase emissions across the product’s lifecycle compared to the current oil-based plastic, acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS).

“It’s like trying to make a bike out of wood rather than steel,” according to LEGO’s head of sustainability, explaining how LEGO was not able to make such drastic changes to its manufacturing process without negating any emissions avoided via recycling.

“We thought it would be easier to find this magic material […] but that doesn’t seem to be the case,” admitted LEGO’s CEO during the backtrack.

Fossil-intensive companies should take note: relying on unknown technologies of the future is insufficient to resolve current challenges.

A similar ‘magic material’ is being dreamt up in multiple industries, but it should not excuse companies from addressing immediate climate risk. As LEGO’s embarrassing saga shows, there is no guarantee that such technology will arrive in time, or at all.

The Scope 3 conundrum

LEGO’s need for a silver bullet alternative to plastic highlights the importance for companies to meaningfully address the full scope of their emissions profile.

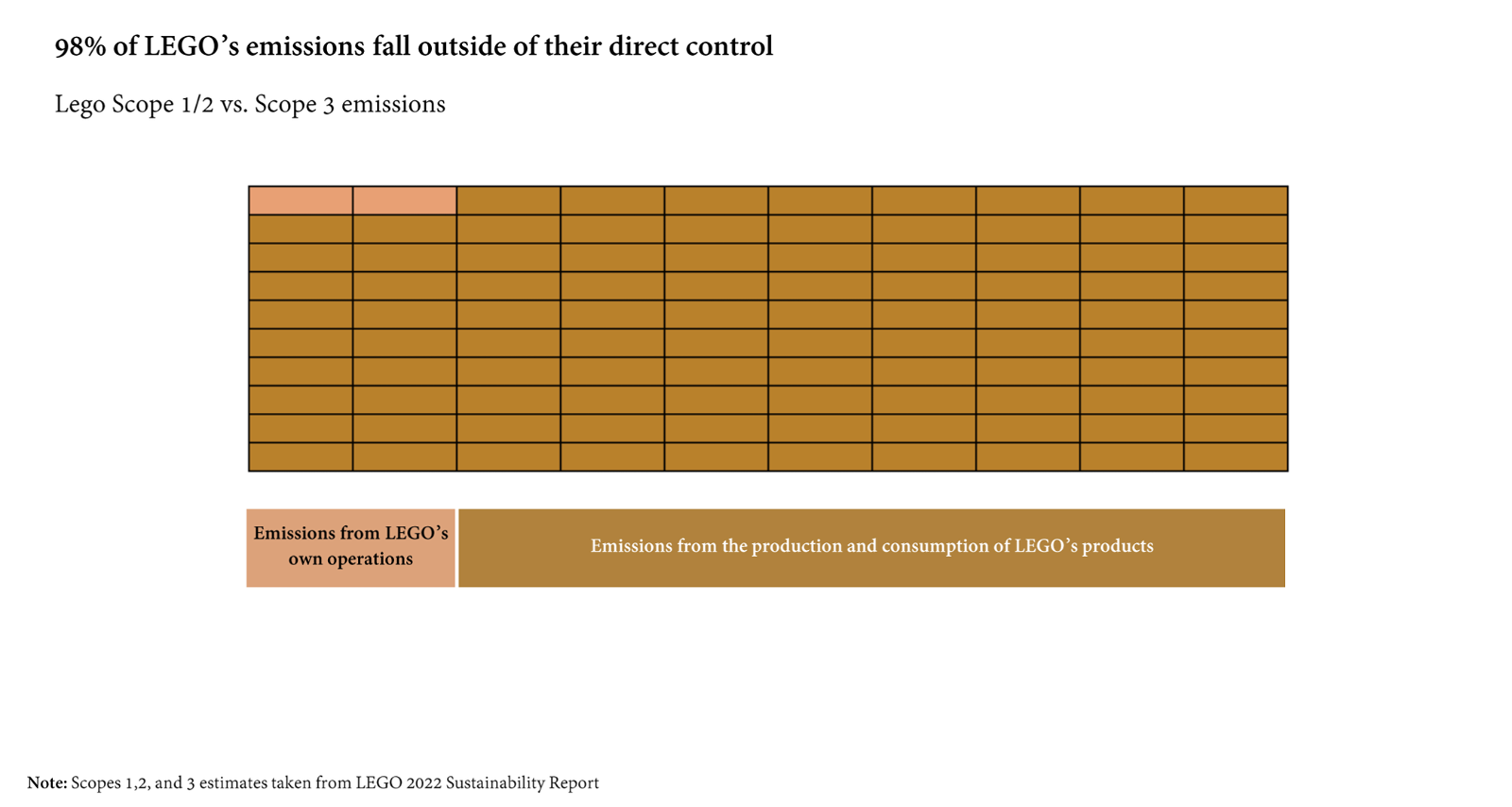

Scope 3 emissions include emissions resulting from buying products from suppliers and the emissions that come from products when customers use them. They are significant for many industries: it is estimated that 75% of total company emissions fall under the Scope 3 category.

LEGO is an extreme case: 98% of its emissions are Scope 3 due to the central role of plastic to the company’s activities.

LEGO has attempted to limit the harmful effects of its plastic usage, but whilst well-intentioned, such effects are limited in scale, highlighting the size of the task for plastic-based consumer products to make a meaningful sustainable transition.

An example is LEGO’s ‘Replay’ programme – a takeback scheme which reuses the unwanted bricks of consumers and repurposes them into new sets – only in the US and Canada. Whilst a creative project, the number of LEGO bricks currently involved is equivalent to less than 0.5% of the 60 billion new blocks the company manufactures in a year.

A laudable move in theory; in practice, one unlikely to drastically reduce the 100,000 tonnes of plastic it creates per year.

Admittedly, LEGO can do more to lower the environmental impact of its own operations – the 2 percent it has greater control over. In its most recent sustainability report, among its top 3 ‘highlights’ were ‘plans’ to construct a solar park in Denmark, and a ‘pilot’ initiative to reuse its pallets in some of its factories in China and Mexico. This suggests a lack of preparedness for the current decarbonization agenda.

However, the elephant in the room remains: without a move away from plastic – that is, without making a dent on the 98 percent – LEGO will never be synonymous with sustainability.

Forcing the shift

Yet who is twisting LEGO’s arm to change?

The sustainability activity of competitors do not worry the Danish toymaker. Current rivals – including Mattel, maker of Barbie dolls, and Hasbro – are making ambitious pledges but with low impact to date. Through brands such as Biobuddi and Mokulock, it is possible to purchase more sustainably sourced building block equivalents. But their limited scale poses little challenge to LEGO’s dominion.

Regulation in Europe, LEGO’s HQ continent, is improving but still playing catch-up. The new European Sustainability Reporting Standards will require publicly traded companies in the EU to disclose Scope 3 emissions from next year. Similar proposals are under consideration in other markets, such as the US. Despite this, history shows greater reporting does not drive proactivity among firms.

This is where consumer action may have to play a decisive role.

LEGO is an extreme example of the importance of consumer willingness to make purchasing decisions that punish sustainability laggards. It is much more tangible for individuals to contemplate purchasing an EV over a fossil-fuel alternative. But sustainability considerations can influence any purchasing decision.

Connotations with family trips to theme parks and birthday presents should not exempt a brand from its climate reality: namely, every plastic LEGO building block purchased today will be lying around in landfills or on the ocean floor in 1,500 years.

LEGO’s record figures suggest that heavy polluting activities are not resulting in any consumer backlash or damages to brand reputation. Does this signal that customers do not know enough or do not care enough?

The LEGO brand name comes from the Danish phrase 'legt godt', meaning 'play well'. Current regulatory and competitive inertia means consumers may need to be the ones to highlight to LEGO that ‘playing well’ is not possible without ‘playing clean’.

See the sustainability performance of Lego on Data Hub™.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.