· 7 min read

By a lucky twist of fate (read markets), the insurance industry has a personal stake in mitigating and adapting to climate change, and inadvertently protecting the environment. The overlapping crises of a warming climate, biodiversity loss, and pollution present grave dangers to life, livelihood and industry. Owing to its expertise over multiple decades in dealing with risks, the industry is well placed to analyse the threats posed by the polycrisis, and suggest ways to manage and mitigate its fallout. The first item on this new column by Praveen Gupta is PFAS, a toxic bioaccumulating substance that has invaded the biosphere, and the insurance industry’s risk portfolio.

Between March and May each year, 15 million Black-legged Kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla gather from across the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans to nest and breed on rocky Arctic cliffs – some making the journey from as far as Florida or North Africa.

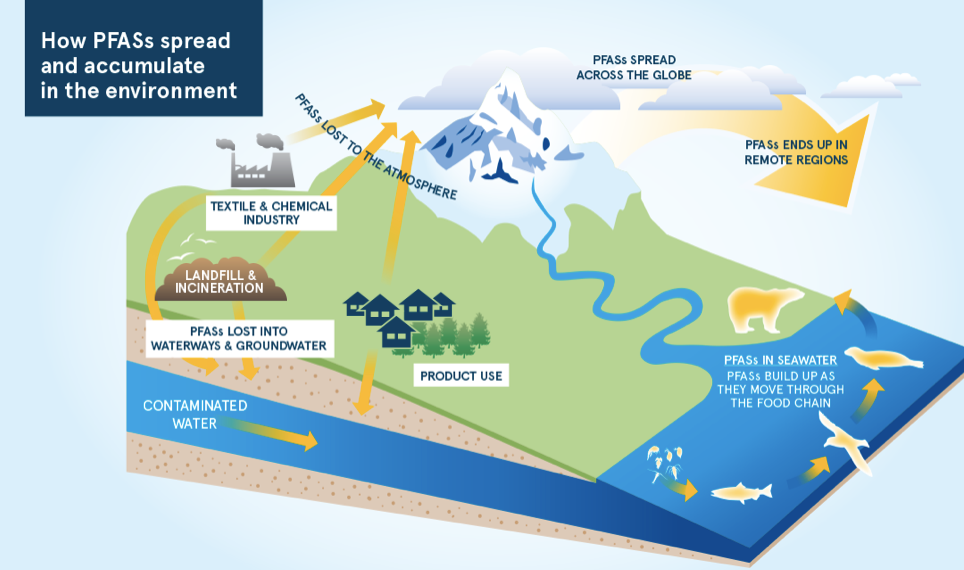

A new study suggests these seabirds don’t arrive empty-handed. They carry souvenirs from the south: forever chemicals picked up in more polluted southern waters. Unlike PFAS in the atmosphere or ocean, contaminants from seabirds often enter the food chain directly. Seabirds are integral to the Arctic food web.

“They’re the main prey of many species,” says Don-Jean Léandri-Breton, a doctoral candidate at McGill University. Arctic foxes, Gyrfalcons, and polar bears prey on seabirds, and nutrients from their guano support plant communities that, in turn, support lemmings, ducks, geese, and a wide variety of invertebrates, Popsci.com writes quoting Hakai Magazine.

Let’s not be blindsided by assuming that climate breakdown is about weather-related risks alone. Pollution and biodiversity loss are very much part of this interplay. Assuming the transfer of such risks to insurance agencies is the panacea – tantamount to the abdication of governance. It deserves special attention.

During the last 100 plus years, two particular environmental and societal risk triggers have had catastrophic implications – asbestos and PFAS. If only we had learnt a lesson from the first, the latter should not have been a problem.

Source: Fidra

PFAS Who?

Billed as the ‘new asbestos’ – given its severe toxic polluting properties – polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) literally stay in a released environment for good. Such compounds have been termed “forever chemicals” owing to the presence of the fluorine-carbon bond, which is the strongest bond in organic chemistry. PFAS is an umbrella term encompassing human-made chemicals used to make products stain and grease resistant. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has identified some 12,000 substances as PFAS. High concentrations of PFAS lead to adverse health risks in the exposed population.

They are used in a wide variety of applications, from the linings of fast-food boxes, toilet paper, feminine hygiene products, most cosmetics to personal care products including lipstick, eye liner, mascara, foundation, concealer, lip balm, blush and nail polish. PFAS are present in non-stick cookware such as Teflon, fire-fighting foams and the insulation of electrical wire. Dental floss, shampoo, mobile phone screens, wall paint, furniture and adhesives all contain PFAS.

Looking back

Nadia Gaber with Lisa Bero and Tracey J. Woodruff made damning revelations in their 2023 paper The Devil they Knew: Chemical Documents Analysis of Industry Influence on PFAS Science: “Our review of industry documents shows that companies knew PFAS was highly toxic when inhaled and moderately toxic when ingested by 1970, forty years before the public health community (emphasis added). Further, the industry used several strategies that have been shown common to tobacco, pharmaceutical and other industries to influence science and regulation – most notably, suppressing unfavourable research and distorting public discourse.”

This is eerily similar to what went down with climate change awareness. The American multinational oil and gas corporation ExxonMobil knew as early as 1977 about climate change. This was 11 years before it went on to become a public issue.

Ever since this group of synthetic chemicals have been used in consumer products and industry at least since the 1940s, they have invaded our land, water and air. Once they enter the environment, PFAS tend to break down slowly, all the while building up in animals, people, and the environment (bioaccumulation). While research about the correlation between concentrations and health impacts is underway, we know for certain that PFAS cause decreased fertility, developmental delays in children, higher cancer risk, and weakened immune system, among other impacts.

“The lack of transparency in industry-driven research on industrial chemicals has significant legal, political and public health consequences. Industry strategies to suppress scientific research findings or early warnings about the hazards of industrial chemicals can be analysed and exposed, to guide prevention,” emphasised Nadia Gaber and team.

USA and UK

Flooded by drinking water lawsuits and under pressure from regulators, US insurers have begun to vigorously ring-fence against catastrophic damage to their balance sheets. Will a pushback from insurers prevent the manufacture of similar products in the future? Perhaps not.

Praedicat estimates that the United States’ cleanup costs for PFAS-contaminated water alone could exceed $400 billion for insurers. Such amounts do not include potential losses in product liability, personal injury, and director and officer lawsuits. If this prediction turns out to be accurate, losses may be beyond the financial resources of the US property and casualty (P&C) insurance industry. Across the Atlantic, the number of sites identified as potentially having been polluted with banned cancer-causing “forever chemicals” in England is on the rise, and the Environment Agency (EA) says it does not have the budget to deal with them, reported the Guardian.

Ultimately, it is too late in the day to merely react upon realising that the insurance industry cannot sustain PFAS any longer.

India’s PFAS Situation Report – 2019

Based on a study by Toxics Link and IPEN, this report is a survey of information available on PFAS in India. These substances have raised increasing concerns on account of their wide use in processes and products and toxic properties that lead to wide dispersion and water pollution.

The principal findings being: No PFAS are regulated in the country. India became a Party to the Stockholm Convention in 2006 and the treaty added PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, a subset of PFAS) to its global restriction list in 2009. However, India has not accepted the amendment listing this substance and it is unregulated, along with other PFAS.

PFAS pollutes rivers, groundwater, and drinking water. They are found in the Sundarban mangrove wetlands and cause particulate air pollution. They contaminate breast milk, fish, and pigs living on open waste.

Way forward

Rather than giving a long rope to insurers and banks as in this case, where insurers in the US and Europe now believe PFAS is like a building on fire – why shouldn’t financial regulators have the right to veto anything societally and environmentally damaging? Insurers, reinsurers, and banks have all the sensitive insights before greenlighting a project.

Shouldn’t financial institutions, before they fund such projects, and insurers, before they let such risks be transferred to their books, satisfy themselves about potential unintended consequences and catastrophic harm?

We need not only a top-down risk management approach but also a uniform global process, so as to:

1. Reduce the scope for national deviations, and enforce uniform rules to ensure a level playing field.

2. Strengthen processes that ensure that financial institutions are following the financial regulator’s rules and regulations by developing global frameworks.

3. Integrate climate risk into all financial regulations, addressing the financial dangers of stranded assets (assets that have lost value) – well beyond fossil fuel – to prevent massive future losses.

4. Regulate PFAS use in manufacturing And why not? Here is a risk inherently intergenerational and cross-border by nature. It has the potential to fuel a polycrisis in an interplay with environmental and societal risks – well outside the grasp and realm of insurance.

The insurability of such risks calls for a more informed and strategic assessment and oversight. We cannot afford to continue overlooking the externalities.

This article is also published in Sanctuary. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.