Our Greatest Enemy

· 7 min read

Time is your greatest enemy

- Top Gun: Maverick

This is Maverick’s first lesson when tasked with teaching a younger generation of fighter pilots. Nobody knows better than him how to cut corners in the air and skim over sand dunes. He is the master of seconds.

Yet throughout Top Gun, a longer scale of time overlays the narrative, where Maverick confronts age, loss, and memory. We discover a man ill-equipped for the future. Once in-flight targets are met, what comes next?

The film engages with the intense pressure of time-bound windows of opportunity, both short and long. His relationship with the younger “Rooster” deals with the consequences of missing them.

We're feeling this tension between short and long scales of time every day in our efforts to limit planetary overshoot. On the one hand we must act now or accept to become spectators of climate breakdown. As I write this France undergoes historic fires, Spain historic droughts, China historic floods, and a glacier in the Dolomites has collapsed. Russia forces fossil fuel scarcity onto Europe and food prices spiral worldwide. Our present is warning us of our future.

On the other hand, deep decarbonisation won’t happen overnight. We know this because we’re timing the process. 1.5-degree peak in 2025, nature positive by 2030, net zero by 2050. Scenario analysis and science-based targets locking dates into corporate strategy and government policy are the promises we’re making to the future. Just like Maverick doesn’t switch on autopilot until the last second to then crack his fingers ready for action, organisations are building the skillset to fly and sustain transformation over time.

But long time must be more than a date and a technical roadmap. The Energy Transitions Commission says "it is undoubtedly technically possible to achieve net-zero emissions by around mid-century at very small costs". If we have the technology and resources to decarbonise at scale, why are all indicators going darker red? Lack of behaviour change and political will are important factors. And they lack precisely because short-termism is locked into Western practices of human organisation.

Long-term resilience is absent from the way we consume. Fast fashion, fast food, fast life. There is a complete disconnect from the simple fact that our consumption – through its social and environmental footprint – destabilises the interest of our future selves and the multitude of other members of our community, the biosphere.

Long-term perspectives are absent from our information networks. The 140-character attention span refuses subject matter complexity. At best news channels feed us simplified snippets of the future, at worst politically charged deformations. Climate scientists, meteorologists, and activists being portrayed as alarmists are constantly resurfacing on television. Another film, Don’t Look Up, captured this perfectly.

Long-term debates are absent from our democracies, incapable of existing separate from their electoral calendars. Politicians’ rushed and highly calculated treatment of era-defining issues prevents substance from actually reaching voters. In April, contenders for the French presidency spent a mere 17 minutes of a 2.5 hours debate presenting their long-term energy plans. Food, biodiversity, and climate adaptation were absent altogether. Nor do any elected officials or candidates admit the true costs and time required for an energy transition. The construction of political narratives is a game of maximal short-term gain, and the interest of future generations doesn’t enter those calculations in their current form.

Reasons explaining this appetence for immediacy are numerous, but at their core lies our faith that markets and efficiency can infinitely enlarge a pie that everyone can take a piece from (some much more than others), and that eating it will bring us happiness. Happy individuals and prosperous nations. So we eat more of it, are forcefully fed more through our screens, and keep asking more from our leaders, who themselves are locked into making more. All this in the knowledge that every extra piece contributes to a future where there is nothing left to eat.

Hence cultural reconciliation with the future must complement the technical orchestration of long time. We should disagree with Maverick and stop seeing time as our greatest enemy. As much as immediate action on all fronts is needed, right now, calls for it are not unlocking change fast enough. Emissions keep rising. Natural carbon sinks are being lost. Species are dying at tragic speed. But a society sick with immediacy cannot heal itself with immediacy. Surely it's the articulation of a long-term narrative for us as a species, a common horizon, that will drive more results in the short-term. In that sense, thinking ahead is in no way a renouncement of urgent action. The time we have ahead of us should be time to see trees grow from seeds we plant today.

Recurrence of cycles has characterised human history. It was punctuated by the changing of seasons precisely because the planet ensured the stability of cycles. Climate change and species loss – consequences of our geological footprint – will make the future anything but cyclical. We are seeing processes unfold that won't stop for centuries to millennia. Humanity has dismembered and massively elongated the timescales of its own existence on Earth.

Those who decry environmentalism as a step backwards don't want to understand that we have changed epoch at a much deeper level, and that we are marching headfirst into it. There is no precedence of entire societies mobilising to meet worsening conditions that threaten collapse for future generations.

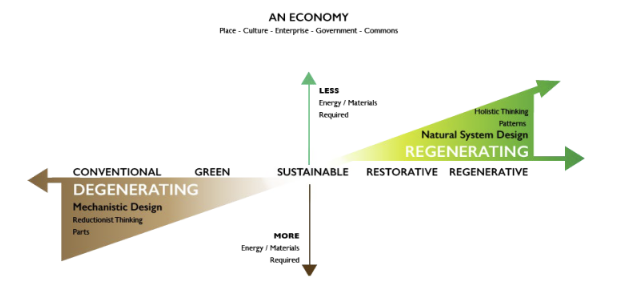

Individuals, institutions, organisations, nations, and regions do not exist independent of long time. By making demands on natural systems through consumption, transport, heating, savings, taxes, and so on, we increase the likelihood of those systems' destruction. What we do in the present connects us to the effects taking place over the "deeper" future. But that's also true for the restoration side of the equation. Initiatives that restore ecosystems will drive benefits over similar timescales. Scientists, economists, and systems thinkers across the world are imagining a society where those benefits would be maximised precisely because society takes the form of the restoration process itself. According to Daniel Wahl, "we have to reinhabit the places and ecosystems we live in as a regenerative and healing presence".

In this scenario, individuals, institutions, organisations, nations, and regions would find value in guaranteeing the health and balance of their surrounding systems over time. An ideal future would be one where each member has unleashed full potential for true wealth creation. Whereas deteriorating global commons are currently slow changes in the background of our embedded society, the restoration of the biosphere must be slow changes taking centre stage in the modus operandi of businesses, states, and individuals. Species intactness, soil biodiversity levels, water quality and capacity, and emissions reduction will be the metrics for success. The guide will be a re-alignment of our culture's compass, away from the maxim of prosperity through instant gratification, and towards one of regeneration over time.

The virtue of a long-term perspective goes beyond a global mission; it is the essence of individual prosperity. Do we not find fulfilment in the things nurtured over time, our family, friends, and enterprises? The joy at buying a house stems from the memories we hope to build within its walls. Imagined futures are the motor of human endeavors. We all know this already, but it lies dormant beneath the ‘stuff’ taking our energy but not improving our overall welfare. To quote Tim Jackson, “investing in the future is the best – perhaps the only – way to render our own lives meaningful today”.

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

The Politics of Planetary Time – Nathan Gardels

Building a Regenerative Future – Daniel Wahl

Regenerative Capitalism - John Fullerton

Political Short termism – Iconio Garri

illuminem briefings

Biodiversity · Nature

illuminem briefings

Carbon Market · Public Governance

Steven W. Pearce

Adaptation · Mitigation

The Washington Post

Biodiversity · Nature

Yale Climate Connections

Effects · Climate Change

Euractiv

Carbon Market · Public Governance