· 8 min read

The Hinkley Point-C nuclear power project in England has a latest estimated cost of £32bn ($US38bn) to complete and will produce over 1.6 billion Megawatt Hours (MWh) over its 60 year lifetime. The deal involves a contracts for difference arrangement, effectively paying at today’s inflation adjusted price £106/MWh ($US127/MWh) for electricity to EDF, the French operator for the first 35 years. This is the equivalent of £100b of revenue with the potential of £172b over its lifetime assuming the same pricing model.

Yet many consider Hinkley to be a bad deal for EDF. Why?

Lazard's levelised cost of energy

To understand energy costs is to understand the Lazard Levelised Cost of Energy (LCOE) report. An annual publication, the report serves as an industry benchmark for different types of power generation. It essentially breaks down the cost of electricity by its inputs. Fuel, construction, maintenance, and financing costs.

According to their assessment on nuclear, if a new project is built on budget and on time, you would need revenue of $130/MWh to make a profit. If the costs blow out, then you need to charge $200/MWh. For context, wind and solar can be built for close to $30/MWh and gas combined cycle, $45/MWh.

These numbers are well above what EDF is receiving but how did Lazard get to this conclusion? And why would EDF still proceed?

The power of Uranium

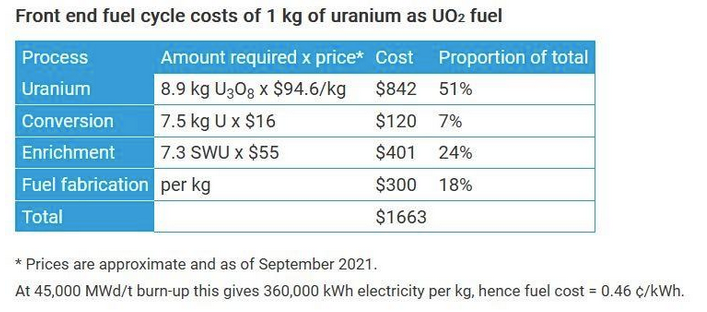

A single kilogram of uranium can produce 360,000 kWh of electricity. It’s the equivalent of 120,000 kg of coal with the added benefit of being dispatchable and with no carbon dioxide emissions.

Lazard assumes a cost of $.85/MMBTU for fuel. With a 33% thermal efficiency which is about the same as a coal plant, it’s the equivalent of a fuel only cost of $9/MWh. The World Nuclear Association, estimates this cost even lower at less than $5/MWh.

Considering the benefits, it’s an incredibly cheap form of fuel and has driven many countries to see a future in nuclear power. But fuel with this level of power requires incredibly sophisticated plants to ensure it's properly harnessed and safe. Building these can get very expensive.

Construction costs

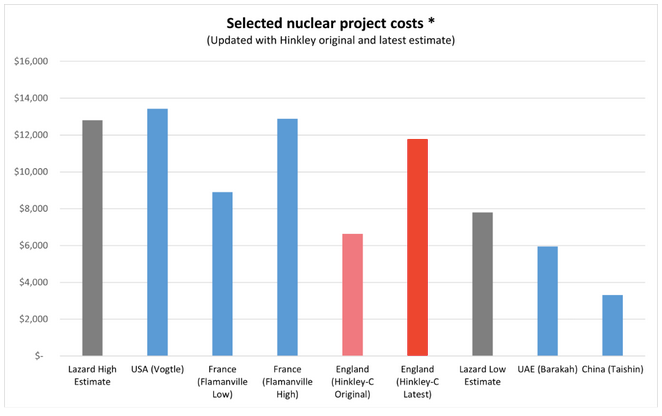

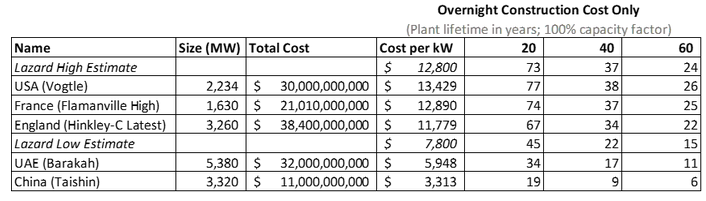

Lazard focuses its analysis on projects in the USA. Currently there is only one project under construction, Vogtle nuclear plant expansion in the state of Georgia. Initially budgeted at $14b, costs have spiralled to $30b.

Construction costs are measured in cost per kilowatt (kW). At a nameplate capacity (size) 2,234 Megawatts (MWe), the $30b current costs gives a unit price of $13,400/kW which is close to the high estimate provided by Lazard.

What about across the industry in other countries?

Looking at other high-profile real-world projects is not positive. Hinkley Point C in England (£32bn, 3,260MWe) is $11,800 per kW at today’s exchange rate and if you believe EDF, Flamanville in France (€13bn, 1,630MW) which has been under construction for 16 years is estimated at $8,900/kW. But if you believe the French legal authorities, it is closer to €19bn or $12,900/kW.

In developing countries, the results appear to be promising. The United Arab Emirates Barakah project ($32bn, 5,600MW) comes in at $5,700/kW and the Chinese Taishan project came in at a very cheap $3,300/kW. Ironic considering it was a French designed plant.

What is the impact on electricity costs?

Dividing the construction cost by lifetime electricity production would give you a simple unit cost. Lazard bases their estimate on a 20-year lifetime which means Lazard would estimate the Hinkley construction cost alone to be $67/MWh.

But Hinkley is estimated to last 60 years which in theory would drop the unit cost down to $22/MWh?

Capacity factors

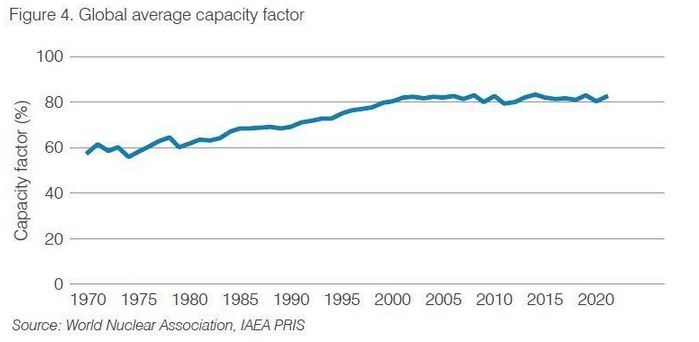

Nuclear power plants run best at close to full capacity. Lazard assumes close to 90% production which is similar to the historical averages reported by the US Energy Information Agency (EIA)

Globally, capacity factors have trended around 82% with France at around 70% and the UK closer to 60%. That means less MWh’s of electricity to pay for the construction cost and is a risk for Hinkley.

Where are the other costs then?

With a fuel cost of $5-9/MWh plus construction adjusted for a 90% capacity factor of $24/MWh, the difference to Lazard is still a long way off from $200/MWh.

The discrepancy at Flamanville gives a clue as to where the remaining costs are.

Low estimates sometimes are just the construction costs. But without revenues flowing in, expenses need to be funded by investors and banks. Normally it’s not a big issue in smaller, easier to build renewable energy projects but as nuclear construction can last 10+ years, the interest on interest accumulates.

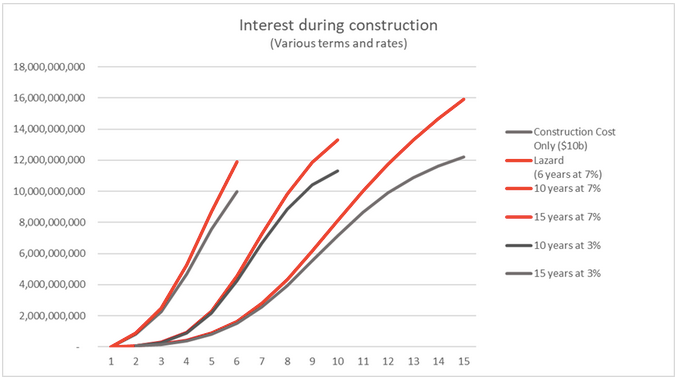

Lazard estimates a project can be completed in 6 years and assumes they use a commercial rate for debt. This alone adds close to 27% extra to the completed cost. But projects can take much longer. In recent years, the World Nuclear Association has seen median construction times getting close to 10 years which would add 35% to the project. For the high-profile projects that blow out to 15+ years, this can add 60% to the completed cost just in interest payments.

But it doesn’t. That’s because many nuclear projects do not pay commercial rates for debt. Governments keen to export their nuclear technologies provide favourable rates in order to win projects. A recent Columbia University study documented rates of between 1%-3% for projects although the catch is it may involve certain countries limited by trade sanctions.

Financing costs

So was Hinkley done over by a loan shark?

Lazard assumes investors want a return of 12% and bond holders will accept an interest payment of 8%. These are kept standard across all types of generation as the intention is not to assess the risk of the project but instead the competitiveness of the technology.

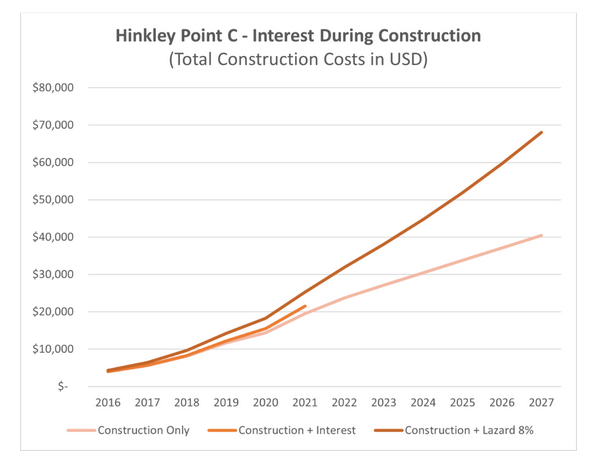

If Hinkley was to pay these commercial rates, the project construction with interest would balloon out to close to $70b. But they didn’t and digging into EDF’s financial statements shows interest costs related to construction was only 1% of capitalised costs in 2017 and 4% in 2021.

So, if they were not funding the project by debt, EDF must have been using their own money to fund the project? This would account for the low interest payments but at the same time investors don’t give away money for free?

Equity

An LCOE encompasses the project and operating costs but funding this does not come for free. Investors invest for future profits as well as any debt carried into the operating period also needs to be paid through interest payments. In effect LCOE is the wholesale cost of electricity, what a company like EDF would sell the electricity to the grid for.

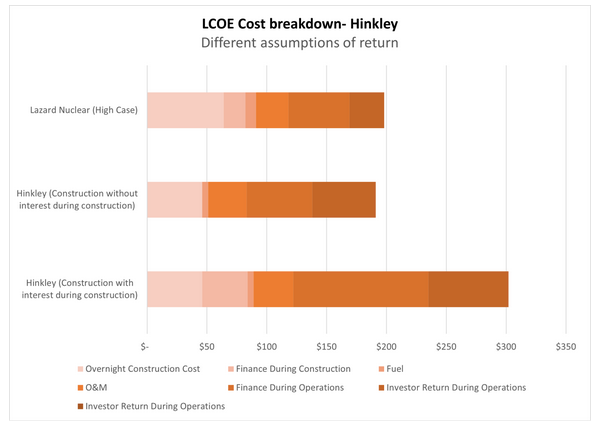

Updating the Lazard model and assuming a $70b project with a 20-year lifetime and 12% investor return, Hinkley would need to charge $309/MWh for electricity to keep investors happy.

Early in the Hinkley project, EDF had stated they were forecasting a 9% internal rate of return (IRR). As the costs have gone up, EDF has reduced their estimates to 7%. A 9% return would mean $290/MWh and a 7% return to $279/MWh.

What about increasing the lifetime to 40 years to account for more revenue?

This would increase the amount of revenue but also means investors want another 20 years of profits. In addition, investors place a lower value on returns that are further into the future. The impact would be minimal, decreasing the revenue needed to $266/MWh.

This same logic also applies to long term costs such as decommissioning and waste disposal. Investors don’t place any weight on events in the distant future.

Is there any way to deliver a 7% return with revenue fixed and cost blow-outs?

Cheap debt would reduce the costs. EDF is now owned by the French government. Accessing government backed rates of debt of 3% would get the revenue needed to $200/MWh but is the French public willing to subsidise British consumers?

So it’s impossible?

Yes and no, nuclear projects need to be seen in the bigger picture.

Engineers talk in terms of “first of a kind” or FOAK for short. The first project in a new country is inevitably the most expensive and as engineers learn from their mistakes, they will be able to decrease costs for future projects. In marketing terms, Hinkley is the loss leader with profits to be made from future projects.

EDF and its partners have proposed Sizewell C in Suffolk, England, with many technical similarities to Hinkley. Will it be better planned to ensure a quicker construction period or make better use of a more experienced workforce? Will this lead to more profits in the future? Maybe, but it doesn’t matter too much because the key learning will be within another branch of engineering.

The financial engineering branch.

EDF has proposed a new funding model. Gone will be contracts for difference where the developer will fund the construction out of their own pocket and incur interest payments. Instead, a regulated asset base (RAD) will be used where consumers pay for the project from when construction starts via their utility bills. If applied to Hinkley, this solves the interest during a long construction period problem. With this fixed, a significant cost of the project will not be borne by EDF and its partners. Although unfortunately, it will be at the expense to the British consumer by effectively prepaying 10-15 years in advance for electricity.

What is the main lesson from Hinkley?

Understand what the true cost will be? Stick to the targets? And maybe make sure you get financial engineering expertise in place which is where the big costs are.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.