Locked up for the long-term: Financial risk mitigation for CCS

· 6 min read

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) is widely considered an important tool in mitigating the global warming effects of excess CO2 in the earth’s atmosphere. A critical piece of CCS is long term geological storage of captured CO2.

The “ground rules” for responsible development of permanent geological CO2 storage in the United States were developed nearly 20 years ago, culminating in regulations, issued by the Environmental Protection Agency under the Underground Injection Control Class VI well program in 2010, that prescribed both the environmental and financial safeguards for project developers. These environmental safeguards were put in place to ensure, to the degree possible, that the stored CO2 remains in its designated space. The financial safeguards, known as Financial Assurance (FA), requires that appropriate funds are set aside, or can be accessed, to address remediation of potential environmental damages resulting from (primarily) unforeseen CO2 leakage.

With these rules in place, progress, as measured by the number of projects, was slowed by inadequate economics. Prospects for financial returns improved with the higher tax credits established by the Inflation Reduction Act, which became law in 2022, and the number of applications for Class VI permits, i.e., projects that include permanent geological storage, now stands at 113.

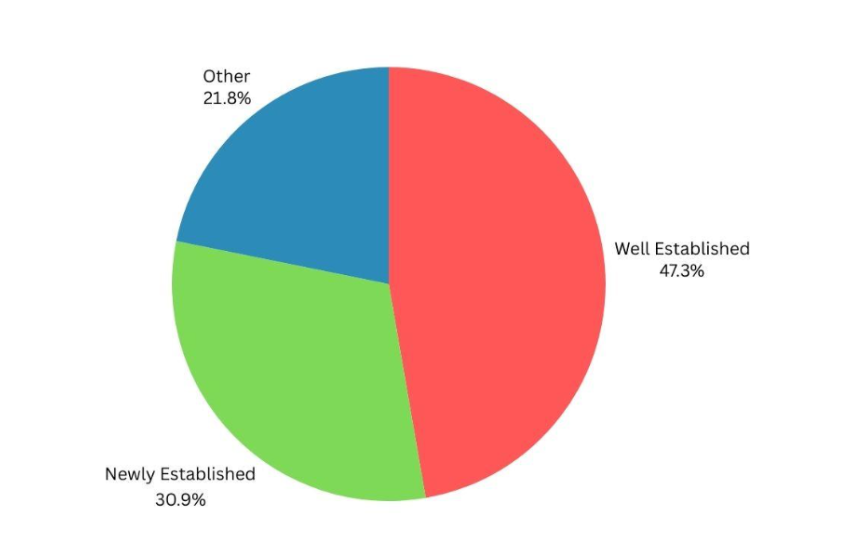

The surge in new development effort has been accompanied by some shift in the nature of the project developer. Now 30% of the applications are sponsored by developers with little or no operating history (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: U.S. Geological Storage Project Developers by “Type”

Source: IEA (2024), CCUS Projects Database

These new developers throw into sharper relief the issues of financial risk management as they pursue CCS projects — and in particular the potential liability should the CO2 leak to the atmosphere during or after injection operations. New developers are more likely to lack the balance sheet to satisfy the EPA’s FA requirements. They are also likely to be far more reliant on Project Finance than others, which comes with different expectations about risk.

And these new developers are more likely to rely on commercial insurance, both to facilitate (raising financing for) geological storage projects and to meet FA requirements. Yet the fact that these developers lack operating history makes it harder for insurers to provide coverage — on top of the challenges the insurers face in assessing the risk of this relatively new “technology.” These developers have also, at least in some cases, sought long term commercial insurance contracts, which creates a further challenge for insurers, again because of limited history as well as how the insurance industry raises capital.

Finally, these developers exacerbate an overhang that exists for any CO2 storage project: the idea that the developer is potentially liable for hundreds of years (or longer). This is well beyond the lifetime of the average corporation, but it can be particularly problematic for single purpose project financed-companies.

Having government assume liability during the Long Term Stewardship (LTS) phase of a geological storage project (relieving developers of such liability) has been enacted in the European Union and selectively in eight U.S. states. Yet this issue remains contentious, with naysayers particularly focusing on the moral hazard such liability release creates.

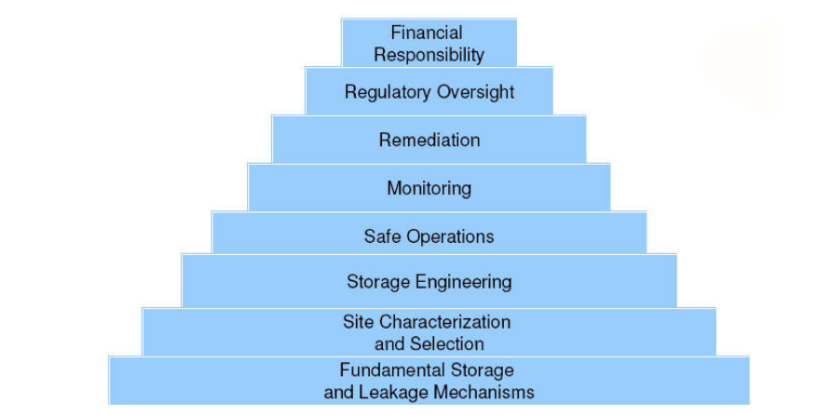

Such concerns appear to be overblown, for three reasons. First, the stringent environmental and FA requirements stipulated for Class VI wells — in effect construct a “storage security pyramid” (see Exhibit 2). Second, developers have decades-long obligations before any such release of liability would be effected. Third, caveats can be put in place to address, for example, deficiencies in operator information that supported site closure. And while some moral hazard discussion in the literature emphasized the risk that the quality of storage locations would decline over time as CCS projects proliferates, this concern appears to be relevant only in the distant future, at which point the industry’s experience with subsurface movement of CO2 could be expected to bring techniques to ameliorate any corresponding risk.

Exhibit 2: The “Storage Security Pyramid”

Source: Sally Benson, Stanford

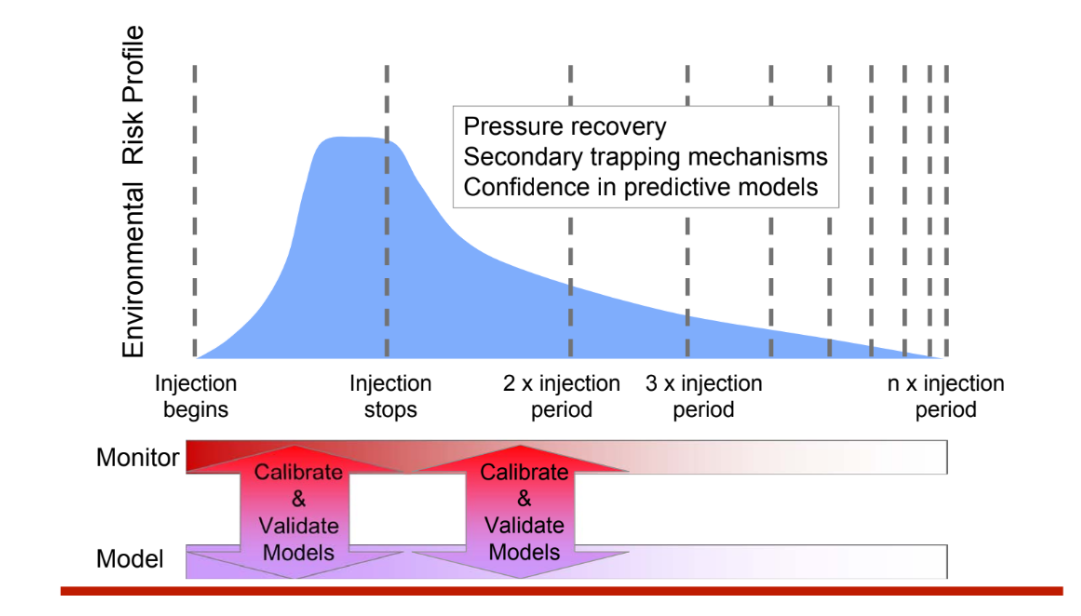

It is also worth noting that it is widely believed that the risk of leakage declines over time once injection operations have ended due to pressure decrease with continued migration of the plume, solution trapping and (to a lesser degree) mineralization of the stored CO2 (see Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3: Risk Profile Curve for CCS Sites

Source: Sally Benson, Stanford University, Global Climate & Energy Project (2007)

The U.S. states with related legislation have applied different conditions to assuming such liability. The resulting patchwork, as well as the associated separate administrative bodies and Trust funds, is suboptimal from a clarity and financial management perspective.

A federal program is a workable solution. A national program can offer efficiency and consistency advantages relative to state-run models.

A national program must have three elements.

It must stipulate that an entity assume responsibility for monitoring and management of the stored CO2 sites.

A Trust must be established and funded to pay for ongoing monitoring expenses and any potential remediation costs should leakage result in damages. It has been suggested (and the state programs have stipulated) that such a Trust would be funded by a “tipping fee” levied on every ton of stored CO2.

Congress must legislate the conditions in which the developer would, or would not, be released from liability.

As to the appropriate size of the tipping fee to be levied on stored CO2, and therefore the size of the Trust, risk analysis that is required for Class VI well approval offers insight (at least for early projects; such an amount can and should be revisited over time to reflect projects’ experience).

In one example for ADM in Illinois, the probabilistic-based exercise yielded an expected value of $0.14/ton of stored CO2. However, this analysis includes risks associated with leakage from pipelines transmitting the gas, the injection well, and known and unknown oil and gas wells in the area (see Exhibit 4), as perceived in advance of all operations. Paring back to the risks that could still be extant during the LTS phase, a tipping fee well below $0.10 per stored ton of CO2 can reasonably be expected to cover ongoing expenses and any potential remediation. This fee is in line with the demands of most of the states that have legislated liability relief.

Exhibit 4: ADM CCS Wells 5-7, Probability-Weighted Costs to Remediate Risk Events

Source: EPA (Petrotek analysis), Payne Institute for Public Policy

Financial risk mitigation mechanisms, including long term liability relief are unlikely, on their own, to foster the widescale adoption of CCS that is needed to help offset the worst effects of global warming. That will, instead, require the advent of new, lower cost, technologies or further economic support. But these risk mitigation measures can help on the margin, including in helping some project developers secure financing, and therefore should be encouraged.

This article summarizes a broader study conducted by the Payne Institute for Public Policy at the Colorado School of Mines. That full report can be found here. illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Gokul Shekar

Effects · Climate Change

illuminem briefings

Mitigation · Climate Change

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Environmental Sustainability

The Guardian

Agriculture · Climate Change

Euronews

Climate Change · Effects

The Wall Street Journal

Climate Change · Effects