Limits of adaptation: how India copes with catastrophic heat

· 8 min read

News from India and Pakistan brings to mind the tragic scenes from the science fiction novel “Ministry of the Future”, which opens with a story of a catastrophic heat wave from which Indians are trying to escape — and almost unsuccessfully, since the energy system cannot withstand the load from air conditioning and the high humidity in combination with high temperature claims many lives. Is it really possible that heat waves that are getting worse every year will make southern countries uninhabitable and turn their inhabitants into refugees?

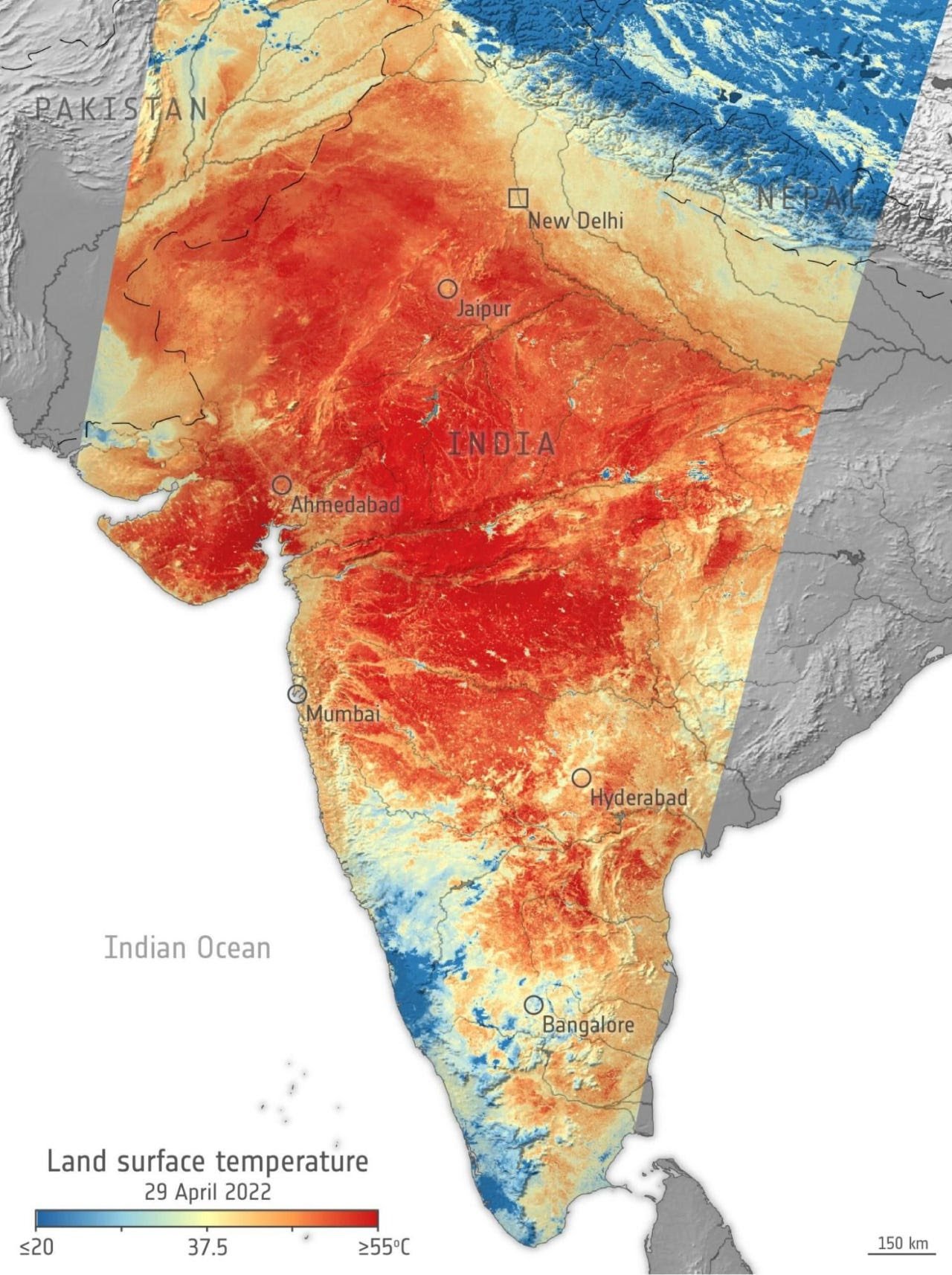

Data from European Space Agency satellites in the last days of April 2022 showed surface temperatures in many parts of India exceeded 60 degrees, reaching 65 degrees Celsius in the Ahmedabad area. This is ten to twenty degrees higher than the usual 55–45 degrees for this season.

“Do you know what 60 degrees Celsius means? Roads and other infrastructure begin to literally melt. I have seen roads melt in Rajakhstan at 50 degrees. We have to be very careful and check the road (before driving),” said one meteorologist, as quoted by The Hindustan Times.

The surface usually heats up much more than the air, whose temperature is measured by weather stations and thermometers outside the window, but these values also broke records in Hindustan. In India, in some regions, absolute temperature records for April were broken, for example, in one of the cities in the state of Uttar Pradesh, thermometers reached 47.4 degrees Celsius, and in the state of Madhya Pradesh — up to 45.9 degrees. In Pakistan, daytime temperatures were five degrees above normal — that is, the values for these dates averaged over 30 years.

To residents of the north, this deviation of five degrees may not seem that big. For temperate and polar latitudes, this is a common story: the temperature here can regularly either rise five degrees or more above normal or drop five degrees below normal.

Hydromet considers abnormal hot weather to be a period lasting more than five days and exceeding average values by seven degrees. But in tropical latitudes, temperatures are generally much less variable from day to day, and such a large deviation from the historical norm is incredibly significant.

Figure 1. Surface temperature on April 29 according to the European Sentinel-3 satellite

Source: ESA

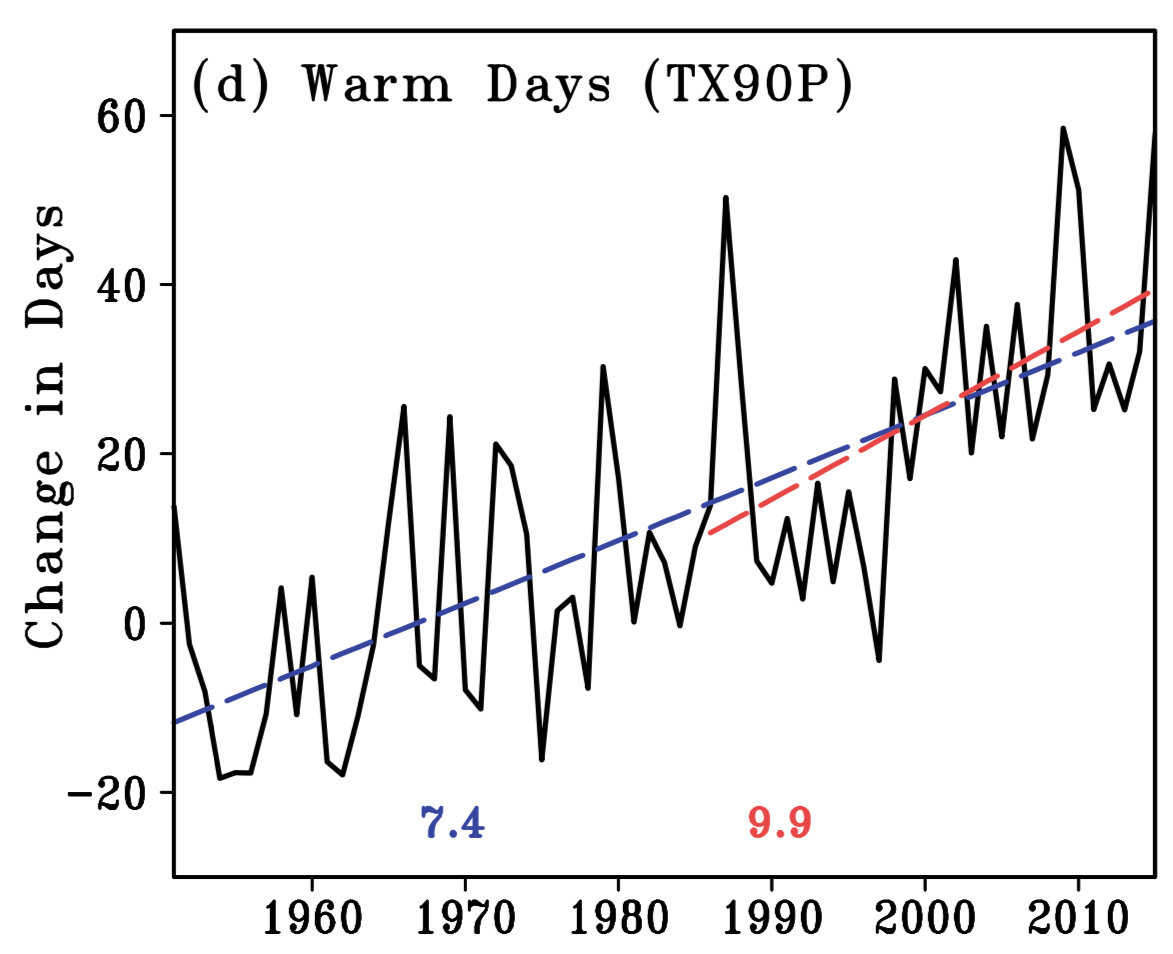

Such a large deviation is unusual, but recently, with global temperatures rising, it is gradually becoming the new “norm.”

This is becoming “normal” in the sense that the climate system is quite predictably responding with more frequent heat waves to anthropogenic pressure, that is, to increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases. In other words, we are now in a transitional stage — from an era when this kind of heat wave was a highly unusual event, to an era when it is becoming routine.

For example, March 2022 in India became the hottest March in the entire history of meteorological observations in the country.

Figure 2. Change in the number of abnormally hot days (with maximum temperature above the 90th percentile) in India

Source: Assessment of Climate Change over the Indian Region / Springer Open

But March is generally a much cooler month, and April and early May are exactly the hottest time of the year in India and Pakistan. The sun is already extremely high, and a lot of solar energy is coming, but the monsoon has not yet reformed. There is monsoon circulation in the region, which is caused by different rates of heating and cooling of land and ocean — the ocean has greater inertia and does everything more slowly.

Different heating brings with it different pressures, and this already determines the wind regime: the wind blows from a cold surface. That is, in winter — from land to ocean, in summer — from ocean to land. Perestroika should happen soon, but the winter monsoon is still in effect, dry weather prevails, and the period of summer monsoon rains, which effectively extinguish the heat, has not yet begun.

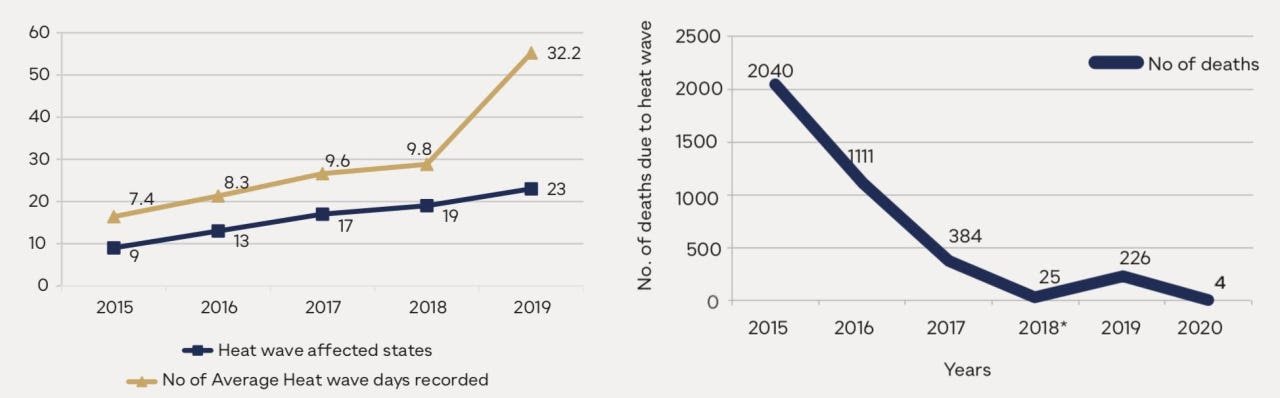

So almost every spring similar messages appear: there is extreme heat, people are suffering from the heat, and there are casualties. In the summer, unfortunately, other messages will come — about heavy rains and the floods they cause. In general, the weather in India is a test, and the question is how ready the population is for them. And in this sense, India is one of the “leaders” in the development of adaptation measures. This is, for example, evident in the contribution of Indian scientists and their activity during the work on the second volume of the IPCC report.

Overall, the country is making significant efforts to reduce the impact of heat waves on the population, adopting plans and implementing measures to adapt large cities to hot weather. Such measures include increasing public awareness, improving the quality and lead time of forecasts, technological solutions, and so on. And the results are already visible: at least according to Indian scientists, despite the increasing intensity of heat waves, the number of people who have died due to this has been decreasing in recent years.

Figure 3. Effectiveness of adaptation measures: heat wave intensity and death toll in India

Source: National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), Government of India

However, if the climate continues to warm at the same rate, the effectiveness of adaptation may decrease. The latest IPCC report clearly showed the limits of adaptation, which strongly depend on the level of global warming. It is interesting here that it was India, at the summit in Glasgow, that insisted on the wording that coal combustion would not stop (phase-out), but would decrease (phase-down).

It is clear that India is squeezed by the need for economic development, because coal is a relatively cheap way to generate electricity, although they have very large resources of the same solar energy. But it turns out that when they oppose the transition away from coal, they support this increase in warming, which is hitting them. A number of works assessing GDP losses show that India, like a number of countries in Africa and Oceania, is among the most vulnerable to climate change. For example, in India, four degrees of warming by the end of the 21st century could reduce the country’s GDP by 14 percent per year, both due to damage to the population and damage to agriculture due to heat and heavy rainfall.

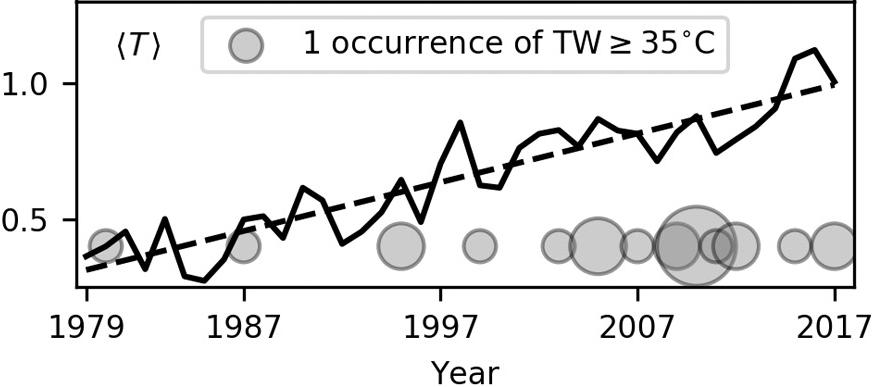

Abnormally hot and at the same time abnormally humid periods put excessive stress on the body, turning off its thermoregulation. This is a serious problem in India and the Middle East. The physiological limit is considered to be +35 degrees according to a wet thermometer. In meteorological booths there are always two thermometers, one dry, and the second wrapped in cambric, the lower end of which is lowered into a jar of water. And on this thermometer, the temperature readings are always lower because energy is wasted on water evaporation.

Based on the temperature difference between the dry and wet thermometers, the current air humidity (relative and absolute) is determined. It turned out that this wet-bulb temperature is also convenient to use to determine conditions in the atmosphere when the physiological limit of the human body is exceeded. Two to six hours in the open air under such conditions leads to the death of a person due to impaired thermoregulation.

What does a +35 degrees wet bulb mean? This is, for example, 35 degrees of heat and 100 percent humidity, or 40 degrees of heat and 76 percent humidity.

Figure 4. Changes in global air temperature (solid line) and the frequency of conditions with a wet-bulb temperature above 35 degrees Celsius (the physiological limit of the body’s thermoregulation)

Source: Colin Raymond et al., 2020, Science/AAAS

The problem is that the frequency of such events is changing, it has already been growing in the historical period, and will continue to grow in the future — the stronger the warming.

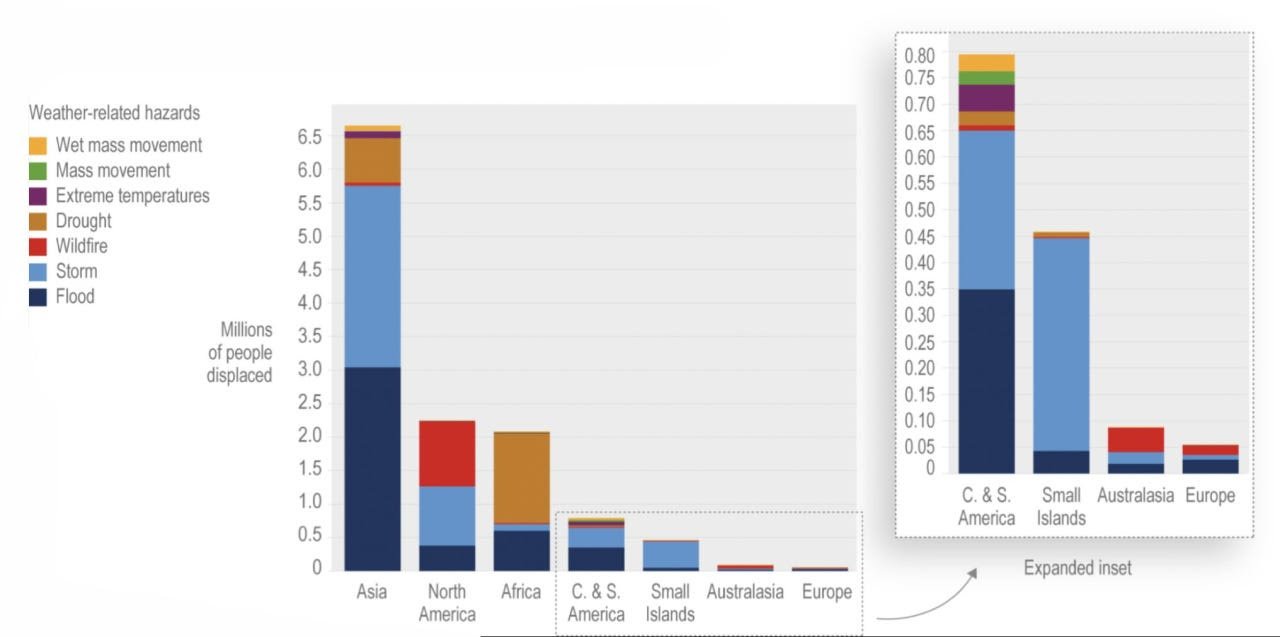

Will there be climate refugees? It’s a good question, but it’s a very delicate term because there are almost no climate refugees as such. Another thing is that every year more than ten million inhabitants of the planet are forced to leave their places of residence due to certain natural disasters. And some of them are intensifying due to climate change.

Figure 5. The average annual number of people who left their homes due to natural disasters in 2010–2020

Source: IPCC 2022

Most of these people are in Asia: from 2010 to 2020, 6.5 million people fled their homes, most of them due to storms and floods (in total, more than 5.5 million due to these two factors). But in Africa, for example, people leave their homes mainly due to droughts (about 1.5 million per year), in North America — due to wildfires. But these are more likely migrants who can return home later. It is difficult to call them fully climate refugees.

As for forecasts that the number of such people will grow, again, all such studies usually make a reservation that this growth will occur in the absence of adaptation measures.

This is partly a self-canceling forecast: scientists talk about the expected increase in the risk of such events, measures are taken, and the risk ultimately decreases due to the measures taken. But skeptics may later recall the forecast and ask: “Yeah, where are those hundreds of millions of refugees? You’ve been deceived again!

Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Effects

illuminem briefings

Climate Change · Insurance

Gokul Shekar

Effects · Climate Change

Al Jazeera

Effects · Climate Change

Japan Times

Climate Change · Effects

The Guardian

Power Grid · Climate Change