In defence of growth

· 19 min read

Over the last 50 years, the world has experienced the strongest period of economic growth in history, with global GDP increasing by 3.5% per year on average, pulling billions of people out of poverty. At the same time, human activity has driven the planet into a climate crisis that threatens to reverse this progress if we don’t rapidly change course.

As the human and economic toll of climate change becomes ever more evident, people are increasingly searching for solutions. A theory that is now gaining traction is ‘degrowth’. The simplicity of its message has given it wide appeal: it is only by abandoning the pursuit of economic growth that we can use less of the world's energy and resources and avert catastrophic climate change. Its most vocal proponents unequivocally proclaim that ‘degrowth will save the world’.

But while many of the movement's objectives are laudable, it has misdiagnosed the problem. Firstly, growth does not necessarily result in higher energy and resource use. In fact, it is now mostly having the opposite effect, with GDP rising and emissions falling in many parts of the world. Secondly, the transition to a low-carbon economy will require massive investments across not only our energy systems, but also to retrofit buildings, redesign transport and manufacturing processes, and transform agricultural practices. To pull this off, we need strong growth to make capital available and underpin the business case for low-carbon technologies.

Fortunately, these same technologies also offer us a path to clean growth, allowing us to rapidly drive down global emissions while creating new, high-paying jobs and improving energy and food security. Clean growth is fundamental to meeting our climate goals. It can drive a new kind of development in the 21st century, replacing the old linear fossil-based economy with a new renewable and circular system. We need as much of it as we can get.

Unfortunately, degrowth is increasingly being considered as a serious basis for policy. In France, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who came third in the last Presidential election and whose coalition has the second-largest majority in parliament, claims that degrowth is now a national necessity. Last week in Brussels, the Beyond Growth conference gathered speakers from around the world to discuss how to put the idea of a post-growth Europe into practice. In the same week, ExxonMobil echoed many of the same arguments put forward at this event in its SEC regulatory filing, claiming that staying below 1.5⁰C would “require a degradation in global standards of living”.

Herein lies the problem: assuming that shrinking the size of the global economy is necessary for tackling climate change plays into the hands of climate sceptics, who use this as a basis to prevent action. It is not only inaccurate, but counterproductive to the movements' own objectives. We should instead stay focussed on what works – supporting clean growth.

It is hard to pin down a single definition of ‘degrowth’. For some, it means either actively reducing the size of the global economy or fixing it at its current level in perpetuity. For others, it means simply putting less focus on GDP as a measure of progress and prioritising other objectives instead. However, all definitions typically agree that if we want to prevent an ecological breakdown, we need a dramatic slowdown of economic growth, with a ‘reduction in production and consumption in the global North’.

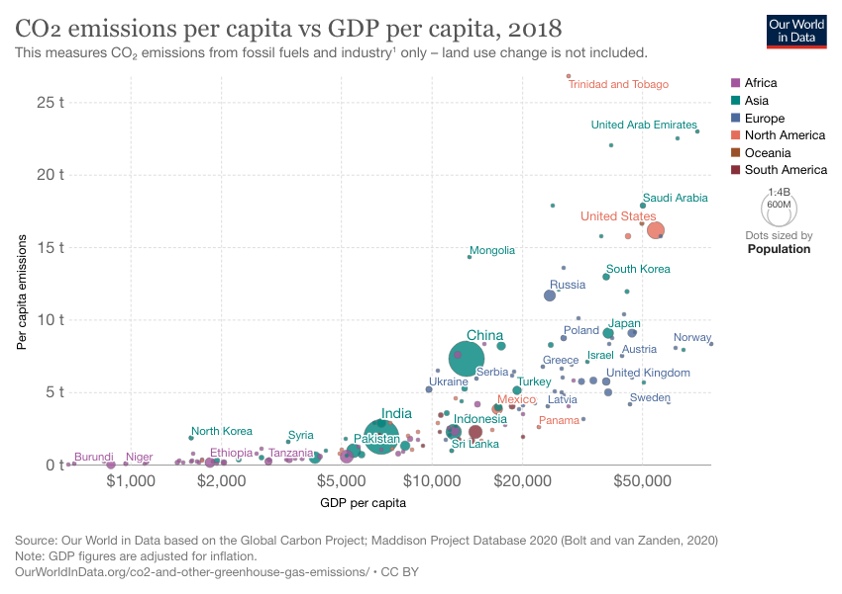

The core argument put forward by the degrowth movement is that economic development necessarily results in higher greenhouse gas emissions and resource extraction. It is therefore only by slowing growth that we can prevent further damage to the planet. To support this view, proponents point to the historic correlation between GDP and carbon emissions or total resource use. As one goes up, so too must the others, the argument goes.

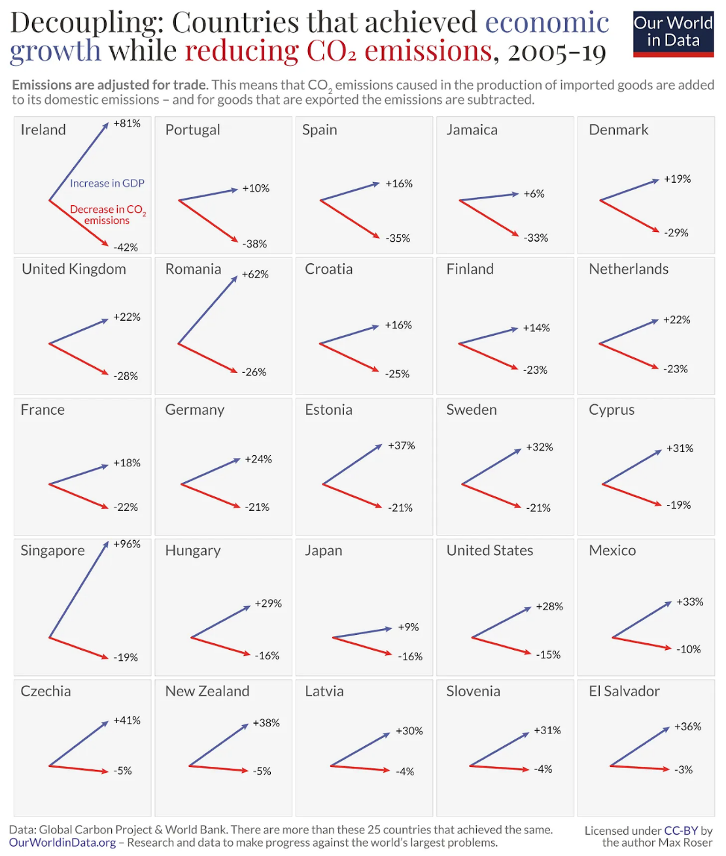

But this argument assumes that what was true of the past will also be true in the future. In fact, this relationship has already reversed in most developed countries, as shown in the last 15 years of data, in which rising GDP has coincided with steadily falling emissions. We have already succeeded in many sectors to ‘decouple’ the two. In some cases, the level of progress has been remarkable. In the UK, for example, total CO2 emissions have fallen back to levels last seen in the 1870s, and the country is already halfway towards meeting its target of reaching net zero by 2050.

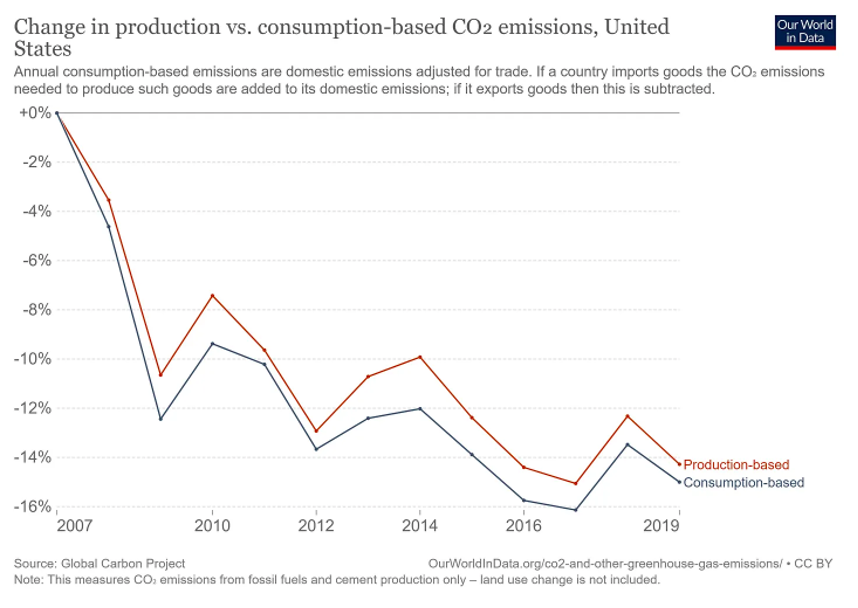

This is not because we have outsourced our emissions to other countries like China. It is easy to see this by comparing national emissions from consumption relative to those from production. Production-based emissions can be shifted from one country to another by moving a factory overseas, for example. Consumption-based emissions, on the other hand, include anything that ends up being used in the home country, including if its production was offshored somewhere else. For example, if a TV is produced in China but purchased in the US, the emissions will show up in the consumption-based emissions for the US, rather than for China.

Looking at the difference between these two measures, therefore, gives us a sense of what share of emissions has been ‘offshored’. The data shows that the US only offshores about 7% of its emissions, while for the EU the figure is slightly higher at 18%. In every case, consumption-based emissions are also falling. In fact, as Noah Smith points out, since US emissions peaked in 2006, consumption-based emissions have actually dropped by more than production-based emissions.

Contrary to popular belief, most rich countries manufacture considerably more goods domestically today than they did before the hyper-globalization era. US industrial production is up over 40% relative to 1990, while in the EU the same figure has increased by 33%. Germany, famous for exporting heavy machinery around the world, has had a positive trade balance for several decades while also managing to reduce total emissions by over 40%.

Similarly, rich countries have been slowly reducing their total material use over time. The US, for example, has increased its crop production by 55% from 1980, while in the same period reducing water use by 18%, fertiliser inputs by 23% and total land area used for agriculture by 7% (returning an area of land the size of Indiana to nature). Total volumes of timber and many types of metals have also fallen in absolute terms while both the economy and population have expanded.

Emissions and resource extraction are therefore not falling in rich countries because of offshoring, but rather because of technological progress. Over the last few decades, we have made radical improvements in energy efficiency and the deployment of renewables. Most wealthy nations have not only managed to reduce total energy demand, but also replaced large amounts of dirty energy with cleaner forms.

As Andy MacAfee points out in ‘More from Less’, new technologies have also allowed us to dematerialise the economy, producing more things with fewer materials. Producers have progressively found ways of using inputs more efficiently and substituting rare resources for more plentiful ones. For the most part, this has happened because of growth, not in spite of it. It has required massive capital investment and spending on innovation, which needs to be funded. It has also been supported by smart regulation that taxes pollution and incentivises innovation.

However, none of this is happening fast enough yet. There is still no credible pathway to limit temperature increase to below 1.5°C based on current national commitments, and GDP has not yet decoupled from either emissions or total resource extraction at the global level. China and India, who now jointly make up for almost two thirds of global emissions, still have both rapidly growing economies and emissions. It is a tempting conclusion therefore to suggest that we should slow or stop growth to save the planet. But this is a distraction from what is actually desperately needed: more clean growth.

The negative aspects of modern society often associated with growth – rising inequality, over-consumption and waste – can lead us to forget what growth has given us in the first place. Growth, or the ability to produce more and higher quality goods and services, has lifted most of the world out of desperate poverty in a remarkably short period of time.

Before the industrial revolution, more than 1 in 3 children died before the age of 5. From this point to 1950, this figure halved, before dropping again 5-fold from 1950 to today. In the same period, the share of the population living in extreme poverty has fallen from over 50% to less than 10%. This phenomenon has not been confined to rich countries, but has occurred across most of the world, and is the direct consequence of economic growth. It is the result of people progressively learning to make things that improve our quality of life. Growth has given us everything from smallpox vaccines to insulin, cancer treatments and neonatal intensive care units. It has allowed us to progressively substitute back-breaking work with more productive machines, freeing up our time to do other things. It has also meant that we could feed a growing population while massively reducing starvation and malnutrition.

Growth is measured using GDP. Like any measure, GDP is imperfect. It ignores many important aspects of society that are not commercial and fails to account for things like pollution and nature. But it does give a broadly accurate representation of living standards (and has the advantage of being easy to measure). Higher GDP translates to better education, longer life expectancy, and better healthcare, to name but a few measures. There are, of course, obvious exceptions to this rule. The US has a very high GDP per capita but relatively low life expectancy, while Cuba has a very low GDP per capita but relatively high-quality healthcare. But these are outliers that reflect countries' idiosyncrasies; they do not invalidate the relationship.

Despite this progress, the reality is that large parts of the world remain desperately poor. Thanks to the pandemic, inflationary pressures, conflict and climate change, this is getting worse. 650 million people continue to live in extreme poverty, earning less than $2.15 per day. Globally, 15,000 children die from preventable deaths every day before reaching the age of 5. Growth is desperately needed in many poorer parts of the world to allow people to live longer and easier lives.

It is also still needed in developed economies, which continue to face major inequalities; in the UK alone, 13 million people live in absolute poverty, on less than £320 pounds per week for a single adult. With the ongoing cost of living crisis this year, more than 1 in 10 people reported being hungry in the past month because they lacked enough money to buy food.

The degrowth movement argues that instead of more growth we should focus on providing basic services for everyone through income redistribution. But the extent to which we can do this depends on our ability to collect tax revenues, which depends on growth. A strong welfare state, public healthcare and universal life-long education must be funded. As life expectancy increases and the population gets older, we will need greater growth and productivity to ensure we can continue to afford our current level of public services, let alone expand access and improve quality. Simply increasing the tax burden every year will not be enough.

Even if this were not the case, it would still make sense to pursue growth. As we have already seen, growth does not need to be extractive or polluting. It is simply a measure of the value of goods and services in our economy, which could come from any new innovation or improvement in productivity. A new, more efficient management technique can increase GDP. So would a new app that cuts waiting times at hospitals. So too would software that helps companies eliminate waste along their supply chain. If we turn our back on growth, we also turn our back on all these potential advances that make life better for everyone.

If we are to reach the goals the world has set for itself of both alleviating poverty and stopping climate change, we don’t need less growth. We need as much clean growth as possible. Most of the solutions we need to decarbonise the economy already exist, and unleashing them at scale can tackle both problems at once, offering a more prosperous and sustainable future. Solar power, for example, is now the cheapest form of electricity generation in history. It is also limitless and distributed, so can be set up anywhere without creating concentrated profits like fossil fuels. It is already providing power to communities around the world that often have had none until now. Just ten years ago, 1 in 4 people in India did not have access to electricity. This year, 99% of the population does.

Clean technologies will be the engines of growth in the 21st century and can reshape the economy to be far more equitable. Many developing countries are already launching landmark projects that could see them become major players in low-carbon industries of the future. These can generate massive amounts of investment and high paying jobs. They offer the chance for countries like Namibia, largely excluded from the global economy until now, to harness their vast solar and wind resources and become leading producers of green hydrogen, aspiring to the same standards of living as the West. Crucially, they give us a clear route to decoupling global GDP from emissions by allowing developing countries to skip the carbon-intensive growth experienced during industrialisation in Western nations.

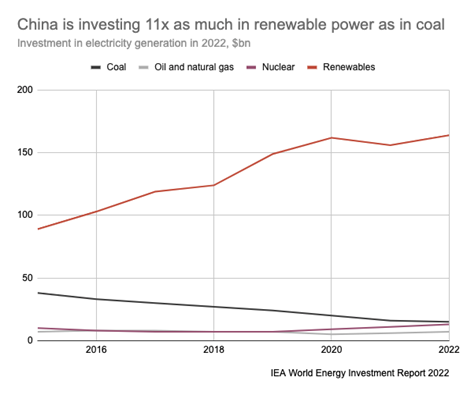

This process is already well underway. Last year, China built more solar and wind capacity than the rest of the world combined, investing 11x more into renewable power than in coal. In fact, global decoupling may already be happening. Recent evidence suggests we may already be close to peak fossil fuel demand both in China and at the global level. In 2021, 85% of all power generation capacity installed around the world was renewable. Electric vehicles now account for over one third of all cars sold in China. Even BP recently projected that global oil demand would soon hit its peak and start to fall rapidly. This trend will be further boosted by rapid digitalisation, enabling emerging economies to embrace dematerialized goods and services, like social networks and AI, early in their growth path.

This is not limited to energy. The world has also, it seems, reached peak agricultural land, with the total area of land used for food production declining since around the year 2000 as productivity outstrips population growth. We have, in effect, also managed to decouple food production from land use.

Until now, degrowth has been a relatively harmless idea. If anything, as a philosophical mindset, it is a good way to discourage excessive consumerism and get people to consider the ecological impact of their decisions. But it becomes dangerous when it is taken seriously as the basis of policy. As the conversation now moves from the ‘what’ to the ‘how’, it is becoming clear that degrowth makes little sense in practice.

For example, one of the more extreme policies suggested by degrowth advocates is the active contraction of the global economy. A recent paper in Nature argued that such an approach should be ‘thoroughly considered’, claiming that shrinking the economy by 0.5% per year would be ‘less risky’ than technology-driven pathways to reach net zero. The proponents of this policy idea fail, however, to put forward any ideas for how to implement this in practice, though it does acknowledge that ‘challenges remain regarding political feasibility’. This is quite an understatement for what would amount to the forced closure of massive portions of the global economy each year. It would require taking decisions on which businesses should shut down and on how to compensate the workers. It is difficult to imagine a peaceful, let alone, democratic political solution.

Another proposal put forward by the degrowth movement is to cap the size of the economy at its current level. However, if we were to theoretically freeze GDP at today’s levels, we would immediately condemn over 10% of the world’s population to continue to live under the poverty line, and half the world to live on less than $7 per day. To resolve this issue, degrowthers suggest a system of wealth transfers across the world to ensure everyone has approximately the same minimum level of income. This overlooks that transferring wealth from one part of the world to another does not necessarily result in an equalisation in standards of living. But even if it could, this level of taxation and transfer is inconceivable in the real world. As Branko Milanovic points out, if we were to try redistributing incomes globally so that everyone had $17,000 per person per year (the current global average), we would need to ask 86% of people in rich countries to give away a major share of their incomes. This would include many of the poorest in society, who would need to accept an ever-lower standard of living than today.

More moderate degrowthers focus on policies that de-prioritise growth and limit excessive consumption instead, such as taxing long-haul flights, second homes or red meat. Some of these policies make a lot of sense, and will absolutely be necessary. But these measures alone are not enough to deliver the deep decarbonisation we need across society to reach net zero. Measures to limit consumption, while positive, are a relatively small part of the solution. The recent COVID pandemic provides a good demonstration of this. There has rarely been a time where more stringent limits were placed on human activity, with half the world effectively confined to their homes for months on end. Yet, global CO2 emissions only fell by around 5% during this period.

We have less than 30 years to switch our entire global energy system to zero-carbon sources, prevent any further deforestation and return large amounts of land to nature. This requires profound, structural changes to our buildings, industrial process and agricultural system, which will need massive, sustained investment. To reach net zero, we need to go far beyond reducing consumption and reshape the global economy around renewable and circular technologies. This will require an increase in the level of capital going to low-carbon solutions from around $1 trillion to $3.5 trillion per year. We cannot wish away the need to heat our homes, produce medicines, grow food, and transport goods around the world. We will need clean growth to replace all our fossil-based systems with zero-emission alternatives.

If the climate movement is to succeed it must offer more, not less. It must demonstrate that a net-zero world is one where people are better, not worse, off. Basing an entire political movement on sacrifice, rather than hope, never wins votes. It is also not necessary. In most cases, climate solutions offer us the opportunity to live better lives in a greener world. Renewables will give us cheap, almost limitless energy. Insulation and electric heat pumps will give us warmer homes. The electrification of transport will mean people can travel further for the same amount of energy. This will mean more, higher-quality clean growth.

The degrowth movement argues that society is obsessively fixated on boosting GDP at the expense of other social objectives. Yet the reality is that countries do not focus solely on growth by any stretch of the imagination. If we did, things would look very different. In the UK, where we have had sclerotic growth for the best part of a decade, we could easily boost growth by increasing immigration to the UK, building more homes, or cutting permitting timelines for renewables. We could even try something completely radical like joining the European single market. We have done none of these things because policy is the outcome of a complex process reflecting a variety of priorities, of which GDP growth is but one. Indeed, GDP per capita in Europe is almost 40% lower than in the US, largely due to different political choices about what society should prioritise.

Far from focusing too much on growth, we still do not focus anywhere near enough on clean growth. It is clear that much of the growth in our current system still comes from the destruction of resources at the expense of future generations. But we have now seen that in most rich countries, economic growth can mean less - not more - carbon emissions, resource use and land conversion. In this context, reversing this clean growth would make things worse, not better. We now need to achieve this same decoupling across the rest of the world. We also need to stay ruthlessly focused on bringing millions of people out of poverty. We should of course aim to limit over-consumption wherever possible, but we should be under no illusion that is a very small part of the solution. To solve the climate crisis, we need to build the low-carbon economy of the future, and this means accelerating clean growth.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Benoît Larrouturou

Degrowth · Social Responsibility

Susana Gago

Nature · Degrowth

illuminem briefings

Sustainable Lifestyle · Sustainable Business

Euronews

Degrowth · Public Governance

Oil Price

Circularity · Battery

World Cement

Circularity · Architecture