How to transform the EU’s agricultural system toward nature

· 15 min read

Decades of intense lobbying have made the agricultural sector resistant to transformation. The future of the EU’s Nature Restoration Law is increasingly uncertain due to an alarming degree of polarisation induced by the EPP. In a recent opinion piece in POLITICO, Eoin Drea argued against the EU’s “urban policymaking elites.” What are the EPP’s motives, and what role is there to play for the EU in the transformation toward a sustainable agricultural system?

The context of this essay lies in the political fallout that emerged from what was supposed to be the final significant legislation to implement Ursula von der Leyen’s European Green Deal. With the European elections approaching next year, the EPP took this momentum to reframe the Nature Restoration Law from an essential piece of legislation to a proxy battle along the rural-urban divide.

As such, a major pillar of the European Green Deal has become a political game that uses and self-enforces the rural-urban divide to subvert European people from systemic transformation. The debate is symbolised by the portrayal of a ‘scapegoat’ farmer, although the underlying issue is a product of a growth-obsessed agricultural system that negatively affects both farmers and soil.

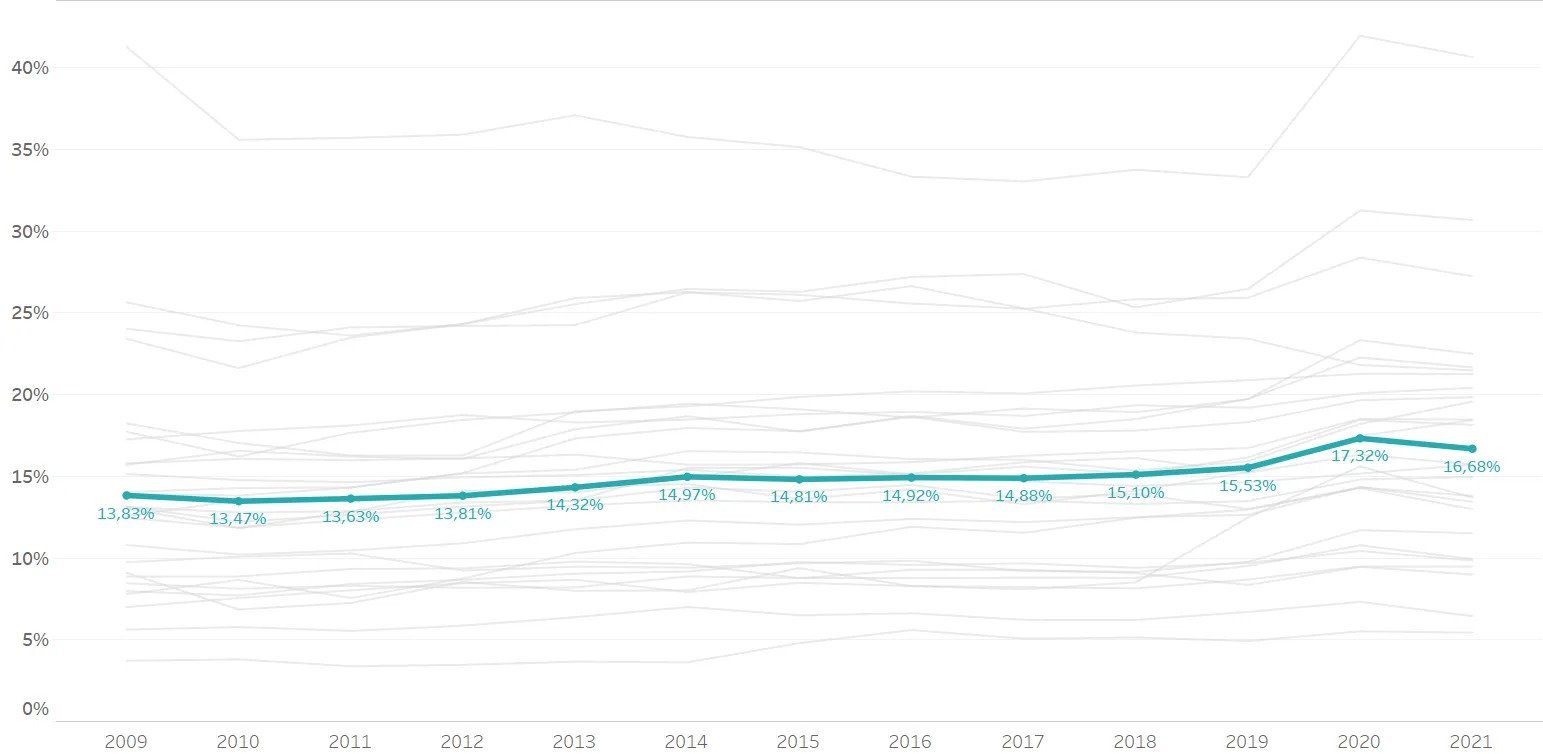

The notion of growth is one that is deeply embedded in our society and the rationale behind most European policies. Even the European Green Deal is promoted as green growth. Agriculture is no different here, partially due to the EU’s own Common Agricultural Policy. Decades of subsidy-induced production growth, paired with a slow transition toward a sustainable model, have made agriculture one of the most emission-intensive industries in Europe (see figure below).

Figure 1. The EU’s agricultural sector share in total greenhouse gas emissions, with the EU highlighted among its Member States

Source: Eurostat

Source: Eurostat

Agriculture is both the victim and perpetrator of the ecological crisis. To see how, let us look at the challenges behind the Nature Restoration Law.

This ecological crisis is often described as a confluence of the biodiversity and climate crises we are facing. While the latter crisis has been subject to high political salience for a while, biodiversity remains quite invisible in policy venues. This changed with the European Commission’s legislative proposal for the Nature Restoration Law. Although already watered by Member States, this proposal urges the preservation and restoration of crucial ecosystems and natural sites across the EU. Hence, it acknowledges the interconnectedness of the biodiversity and climate dimensions.

A substantial part of the European Parliament does not seem to fully grasp the importance of biodiversity, however. MEP Manfred Weber, President of the EPP, is the key actor behind the political game to reject the Nature Restoration Law. On the back of the rural citizens of Europe, the EPP does not focus on the earlier two dimensions of the ecological crisis but rather emphasises a third, social dimension.

The social dimension of the ecological crisis entails, among others, the impacts of climate and environmental policy as distributed throughout different layers of society. What Weber is doing might as well be straight out of the electoral playbook of the populist parties he likes to dismiss: self-enforce societal cleavages for electoral gain. In this case, the rural-urban cleavage and the European-national cleavage are instrumentalised. Weber and the EPP have inflated the rural-urban divide by emphasising how the Nature Restoration Law could reduce the land cover for agriculture and threaten food security in the EU — thereby threatening the livelihood of European farmers.

Hereby, I echo thousands of scientists in their call to state how these claims are not in the slightest supported by scientific evidence. As Weber and Drea sway MEPs and the general public against the Nature Restoration Law, they are actively feeding disinformation and starving our future society. Climate change and biological degradation are threats to food security, not to European policies pursuing its preservation. Let the agricultural industry be known as the main driver of environmental degradation in Europe.

Moreover, Drea claimed to represent the farmers of Europe, as they seem to be “disproportionately” underrepresented by a sectoral lobby. Scientific evidence, however, shows that the agricultural lobby is one of the most sizeable in the EU, effectively weakening EU agricultural policy to be both ineffective and expensive. For instance, the agricultural lobby has been key in deteriorating the effect of the EU’s Farm-to-Fork Strategy and, most importantly, the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy.

The agricultural system has been slowing transformative change toward a sustainable society for decades now, and the agricultural lobby has played a significant role in this. Now, the European Parliament has become a venue of increasing polarisation, orchestrated under the EPP. With multiple parties involved, conflicting in values and/or interests, the issue of environmental protection has turned into a very wicked problem.

The European Commission has often been denounced for the way it has — or has not — dealt with the governance challenges accompanied with wicked problems. However, here, the von der Leyen Commission has certainly been a change in that regard, enabling at least some degree of transformative change. The Nature Restoration Law is the most recent and presumably the last major initiative to keep up that reputation. However, it has become a battleground in the fight of electoral short-termism.

Wicked problems are policy issues that cannot be adequately addressed with short-term thinking, typical of electoral cycles. In this case, they require a certain degree of transformation, both in institutional governance and the economic worldview. Let’s start out with the latter.

The concept of degrowth recently entered mainstream economics and the Beyond Growth Movement is rapidly growing. The Beyond Growth Conference in the European Parliament in May proved this, although it was still flawed. As a strategy to live comfortably within planetary boundaries, degrowth offers a way out of the growth-obsessed economic paradigm that has ruled our economic system for decades on end.

Growth interests have made humans addicted to the idea of “more.” To accommodate society’s request for more food, the agricultural system become prone to growth interests as well. Hence, the agricultural lobby has become so strong — since they are able to gain the sympathy of both politicians and consumers on the back of food security. Being susceptible to the pressures of interest groups such as Copa-Cogeca, European farmers do not necessarily benefit from this political and societal sympathy.

Yes, government subsidies have helped farmers to be competitive and make a living. Vulnerability to large agricultural corporations, however, has made farmers dependent on them for their income and how much they should produce. More often than not, corporation requirements for production are much higher than what agricultural land can offer ecologically. Therefore, environmentally degrading techniques have to be used to meet growth interests. Moreover, the social conditions of farmers dependent on large agricultural companies are often not that great either.

This forms a social basis for why Weber’s appeal to the rural-urban divide works so well. However, the solution does not lie in rejecting legislation targeted at restoring and preserving crucial ecosystems. It lies in ridding European farmers of the idea that growth is an insurmountable must to survive. To enable both biodiversity and farmers to flourish, agro-ecology is planting the seeds of change.

Briefly defined, agro-ecology is an integrated concept applying a synthesis of ecological and social principles to the design of a sustainable agricultural system. It is a resilient approach to agriculture that seeks to optimise the interactions between the environment and human activity. As such, it offers a firm social foundation within the constraints of an environmental ceiling — in line with Kate Raworth’s doughnut economics.

Listening to both environmental and social concerns can help to protect, restore, and improve agriculture and food systems in the face of climate stressors. Agro-ecology attempts to reduce dependence on external inputs from large corporations to reduce producers’ vulnerability to economic risk and to build an equitable food system.

Wicked problems are both transboundary and socially complex in nature. These factors typically undermine the effectiveness of traditional forms of governance. EU governance can play a pivotal role in facilitating a joint response, as shown during the most recent COVID-19 and energy crises. Given the transboundary nature of environmental degradation and the social complexity of the transformation toward ecologically robust agriculture, Member States cannot and should not act alone.

Euroscepticists are often eager to dismiss EU integration from the principle of subsidiarity. In EU multi-level governance, entails that policy action should be performed at the lowest most appropriate level of governance to preserve the authority of national and sub-national governments. Eoin Drea, too, blames the EU of losing rural Europe by its own doing. I argue, however, that a growth-based agricultural system — built by large interest groups such as Copa-Cogeca — has ruined farmers and their soil. With European elections arriving soon, it is easy to use a sector in disarray to make political gains, especially if you can pass the problem to a supranational actor like the “bureaucratic elites in Brussels.”

As argued, the problem is not an urban policymaking elite supposedly far from local realities. The problem is transnational environmental degradation, in part through the unsustainable agricultural model pushed by large corporations. Dealing with a transnational policy issue, the EU provides the best level of governance to achieve sustainable policy outcomes. Similarly, natural ecosystems span across traditional borders and policy domains, and policy action needs to span across borders and foster transnational cooperation and binding targets to adhere to.

This coordination entails not only EU-Member State or intra-EU coordination. The EU should adhere to subsidiarity by recognising the importance of local and regional authorities in addressing environmental issues. Local governments are crucial in engaging (rural) communities to address environmental threats, and in implementing EU environmental policies.

The controversy surrounding the Nature Restoration Law is based on unfounded claims and has the potential to block further transformation toward a sustainable agriculture system. The EU’s agricultural system’s resistance to change, fuelled by the interests of powerful lobby groups, has perpetuated an environmentally degrading and growth-obsessed model.

As Manfred Weber sways the EPP into polarising the Nature Restoration Law through leveraging the rural-urban cleavage, he has succeeded in diverting attention away from a sustainable transformation. I argue that much contrary to Drea’s view, the EU is not losing rural Europe due to its environmental policies — neither is the EU making farmers its scapegoats for these policies. Late stage capitalism, rather, is losing its grip on an unsustainable economic model and unfortunately, some of its deepest roots are in the agricultural system.

The alternative to the current agricultural system is not one where climate policy becomes obsolete, but rather one that embraces agro-ecology to prioritise the well-being of both ourselves and our environment. Farmers, their associations, and other EU citizens should therefore not antagonise the EU, but rather promote political leadership that is willing to transform beyond growth.

Rejecting the Nature Restoration Law would send out a signal to the rest of the world that nature should not be prioritised. In the face of the upcoming European elections, long-term interests should take precedence over short-term electoral gains. After all, that is what the EU is made for: to solve policy issues where national action cannot or does not suffice. Brussels is not neglecting its rural constituencies; it is trying to provide a lifeline for a thriving and sustainable future.

This article is also published on the author's blog. Future Thought Leaders is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of rising Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Agriculture · Public Governance

Michael Wright

Agriculture · Environmental Sustainability

Yury Erofeev

Food · Agriculture

Politico

Climate Change · Agriculture

The Guardian

Climate Change · Agriculture

The Guardian

Agriculture · Climate Change