How do sustainability, finance, and technology connect?

· 8 min read

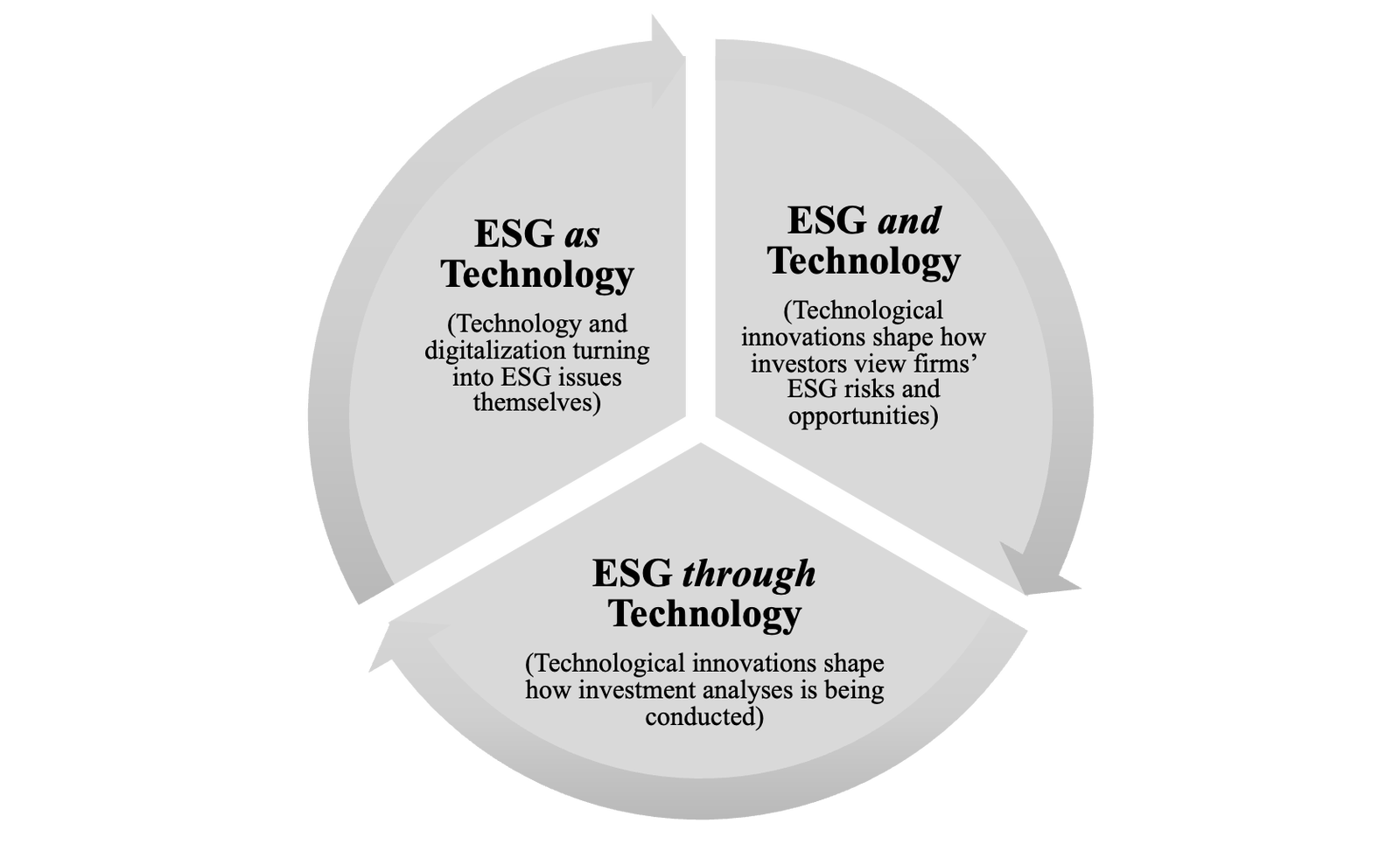

While sustainability and finance are connected through the discourse on sustainable finance and ESG (Bril, Kell, Rasche, 2021), it is less clear how ESG relates to technology. We suggest considering three different perspectives on the relationship between ESG and technology. Naturally, the three perspectives are based on analytical distinctions which overlap in practice. Figure 1.1 provides a summary of the three perspectives.

Technological changes and innovations are disrupting companies’ business models and allow for sustainable business practices to move mainstream (e.g., new battery technologies enabling electric mobility). These changes have consequences for how investors value companies, and how they view risks and opportunities in the context of sustainability. The “ESG and Technology” perspective looks at the many technological innovations in the economy and tries to understand how these innovations can impact the ESG performance of companies (Kell & Rasche, 2021).

ESG-minded investors need to develop basic knowledge of technologies like carbon capture, robotics, battery storage capacity, and hydrogen energy so that they can judge ESG-related opportunities and risks. The “ESG and Technology” perspective also provides a platform to discuss how technology and sustainability reshape entire industry dynamics. Consider, for instance, how new technological developments create so-called ‘sector couplings’ between different industries, such as when energy consuming sectors and energy producing sectors are increasingly intertwined. The rise of electric mobility, for example, requires that the automotive industry is increasingly ‘electrified’ (Appunn, 2018). Such dynamics unfold creative destruction processes that impact how investors assess companies.

There is, of course, no conclusive list of technological developments that an ESG investor should be aware of. Whether and how a technology is impacting a firm’s ESG performance is influenced by many factors, including, but not limited to, the industry a company operates in, the company’s size, its geographic location, and the regulatory environment it faces. Also, while some technologies are well-known by now (e.g., increased battery storage driving decarbonization in some sectors), other technologies are just about to emerge. In 2021, the World Economic Forum (2021) listed self-fertilizing crops, on-demand drug manufacturing, energy through wireless signals, and 3-D printed houses as some of the most promising emerging technologies that can help to address ESG challenges.

Sustainable finance itself has been exposed to massive changes due to digitalization. While a decade ago sustainable finance was mostly practiced through screens (excluding or including firms with low/high ESG performance), more recent innovations in AI and machine learning (ML) have opened up new possibilities for investors to integrate ESG criteria into portfolio construction. These new investment technologies evolve alongside the technological changes in society at large.

Monk and Rook (2020: 16-24) have outlined a short history of investment technology. They conclude that almost each major innovation in investment technology (e.g., double-entry book keeping and telegraph enabled stock-tickers) is related to advances in one (or more) of three capabilities: (1) latency of data (i.e. the speed with which investment-related data can be communicated); (2) depth of data (i.e. the level of detail and complexity of investment analyses); and (3) resource efficiency (i.e. how efficient investors’ organizational resources can be utilized). These three capabilities are interlinked and trade-offs exist. For instance, if investors find ways to obtain and analyze relevant data more swiftly, this can potentially come at the expense of analytical depth (Monk & Rook, 2020: 17). We therefore must debate advances in investment technology against this background. We need to see where new analytical techniques can help investors gain a competitive advantage and at which cost such an advantage may be created.

Recently, the role of AI and ML within ESG-related investment decisions has been much discussed (Selim, 2021). The starting point for such discussions is usually the recognition that ‘traditional’ ESG data does not give investors a comprehensive perspective on companies’ ESG performance. Some problems relate to the fact that most ESG data is self-reported and hence likely to be biased. Other problems occur when focusing on what rating agencies do with this data and the divergence of evaluations that are created due to raters using different methodologies (Berg, Koelbel, & Rigobon, 2020). Given these constraints, AI can be used to advance portfolio decision making, especially in situations where investors want to include extra-financial information (e.g., news items, social media) into the analysis. We can think of AI delivering early “digital smoke signals” (Lohr, 2013) – that is, hidden risks and anomalies that would otherwise escape the attention of investors (Antoncic, 2020). AI can also be used by venture capital investors to make investment decisions. For instance, Antretter et al. (2020) trained an algorithm to make VC investment decisions. They found that the algorithm outperformed inexperienced VC investors while experienced investors fared much better.

Whatever their application, new technologies allow investors to supplement the use of structured data sources with analyses of vast amounts of unstructured data. Sentiment analysis algorithms, for instance, are increasingly used to study the tone that underlies a conversation. Using natural language processing (NLP) such algorithms can extract attitudes and other subjective information from texts. Sentiment analysis can be used to study a company’s commitment to ESG, for example when analyzing data from quarterly earnings calls (S&P Global, 2020). In the end, such applications can meaningfully supplement existing data sources and hence allow for a more fine-grained analysis of firms’ ESG performance.

Technology and digitalization not only affect how ESG is practiced; they increasingly also constitute ESG issues themselves. For instance, consider the role of cybersecurity which can significantly undermine the stability of firms’ operations and hence must be considered within governance-related discussions. Further, bitcoin-related activities (to which some investors are exposed) have a negative carbon footprint and hence impact environmental performance. Some have called this emerging agenda Environmental, Social, Governance, Technology (ESGT) (Bonime-Blanc, 2020). ESGT is important because it emphasizes that some technological issues, which have significant consequences for a firm’s level of sustainability, are not adequately captured by more traditional ESG thinking.

Adding the “T” to ESG does not just imply to find a new acronym or to promote a new framework (we already have enough acronyms and frameworks). Corporations must understand that many technological issues impact exactly those risks and opportunities that ESG analyses are trying to assess. In some contexts, technological issues can be treated as topics that need to be addressed on their own. In other contexts, technological issues will interact significantly with established E, S, and G topics. Consider, for instance, the role of cybersecurity. Through the COVID-19 pandemic working from home has become a new norm for large parts of the global workforce. This exposes firms to new cybersecurity risks, and it also throws up questions on the potential social impact of firms’ cybersecurity measures (e.g., aligning such measures with human and labor rights). Further, a lack of adequate cybersecurity can impact client privacy in cases where potential sensitive and confidential information may be shared unduly (Nasdaq, 2020).

The three perspectives do not exist in isolation (indicated by the arrows in Figure 1.1). Which technologies are used by investors depends on what kind of innovations are mainstreamed within the economy. Also, which ESGT issues become salient depends on the general trajectory of technological developments and their uptake by the finance community.

A possible fourth perspective on the relationship between ESG and technology would be to consider firms’ own reporting practices and how these practices are shaped by technological innovations. Increasingly, firms can produce more granular sustainability data allowing them to zoom in on parts of their supply chain or regional operations (Amesheva, 2017). For instance, Patagonia’s famous Footprint Chronicles allows the consumer to follow the ESG performance of the company’s products along all stages of the value chain (including raw material sourcing). Without doubt, such fine-grained ESG data create higher levels of transparency and can support investment analysis (especially if such data is combined with technologically advanced investment methods). However, as this book is primarily concerned with the investor side of ESG, we do not further unpack this perspective within the forthcoming chapters.

This is an excerpt from Chapter 1 of "Sustainability, Technology and Finance: Rethinking How Markets Integrate ESG" by Herman Bril, Georg Kell, and Andreas Rasche. Published by Routledge. © 2023

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Christopher Caldwell

Ethical Governance · Minorities

Gokul Shekar

Effects · Climate Change

Charlene Norman

Sustainable Business · Sustainable Finance

Responsible Investor

Sustainable Finance · ESG

Responsible Investor

Sustainable Finance · Corporate Governance

ESG News

Sustainable Finance · Corporate Governance