Housing as Public Health Policy

· 7 min read

Our home is our first place in this world. It is the place where we grow up, play, develop ourselves, enjoy family and friends, where we feel safe and rest. It is the place, in the best of cases, where we seek refuge and protection when things get hard. It is from there that we throw ourselves into the world.

Unfortunately we know that is not the case for far too many people in the world. When the pandemic hit in march 2020, what was the one thing that we all heard, no matter where we lived?

We all heard those words. During the pandemic the feeling that housing, our home, serves as a shelter from the outside world, must be minimally safe, habitable and comfortable, was deeply reinforced. The most privileged layer was able to work from home, leave their apartments/homes in the cities and take refuge in rented or second homes, others invested in their homes. In Brazil we all heard the almost never-ending noise of construction, and indeed, the number of home renovations grew significantly during those 24 months.

But, as we know now, and many predicted, the pandemic only accentuated the existing structural inequalities in our society and, as in other crises, it affected vulnerable groups more critically. Globally, the number of people living in poverty rose after decades of steady decline and the gap between the wealthy and people living in poverty widened. The staggering numbers are not coincidences but a clear sign that structurally our societies are not healthy and things must change.

While 5 million people became millionaires and the 10 richest men in the world doubled their wealth during the pandemic, there are according to the World Bank "about 97 million more people are living on less than $1.90 a day because of the pandemic; 163 million more are living on less than $5.50 a day. Globally, three to four years of progress toward ending extreme poverty are estimated to have been lost." In Latin America we had a regress of 27 years, according to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

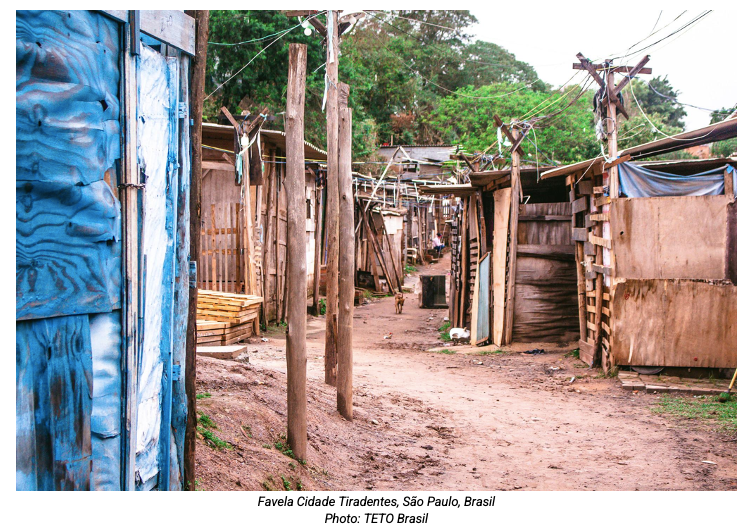

Furthermore, according to the United Nations over 1 billion people live in informal settlements around the world. How did people endure such a time in their homes? Did people feel comfortable and safe? Did they have a bathroom with adequate sanitation, drinking and running water?

The truth is that rapid urbanization and population growth have been outpacing the construction of adequate and affordable housing since the beginning of time but on top of that rents are rising faster than incomes. In a survey conducted in 200 cities globally, by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in 2019, showed that 90% of cities were found to be unaffordable to live in, with the average home costing more than three times the average income.

So, people who cannot afford to participate in the formal market at all, have to resort to alternatives ranging from co-living, living in dangerous and illegal conditions, living on the streets, and building their own homes in informal settlements and so on. This happens from all over the globe. I saw this both up and close when working with the City of New York in a Basement Legalization Programm in East New York, to the favelas in Brazil. It is imperative to highlight that the 1 billion people living in informal settlements will be the ones suffering the hardest consequences due to the climate crisis we have created.

Firstly, more and more institutions have been raising the alarm about the effects of housing on health and the structural inequalities that lead to those. Most people might not know, but our health (mental and physical) is in its majority (55% according to WHO) determined by social factors, non medical aspects that influence health outcomes. Housing is of course, a very important social determinant, having led the World Health Organization to publish in 2018 new guidelines on housing and health.

"They are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. These forces and systems include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies and political systems." - WHO

In the last couple of years, we have seen some interesting and serious investment moves. One example is the Boston Medical Center in the USA, which is going to invest USD 6.5 million in social housing as a public health solution for the Boston community. The initiative will support various civil society organizations in the construction of housing for low-income populations.

In the impact evaluation carried out in partnership between TETO Brasil and Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV), released in November 2021, the following data stands out: solutions such as the construction of emergency housing have a positive impact on the sense of well-being of families who today live in extremely vulnerable living situations.

The study that interviewed a total of 530 people in 31 favelas in 6 states in Brazil showed that when comparing groups that had built their house with TETO versus those who had not, these were the following main effects:

Our impact evaluation joins the hall of research studies on housing and health, with the particular angle of informal settlements which are so often out of reach for people in academic environments.

Secondly, even though the right to adequate housing was declared in 1948, the housing crisis of the last few years has reached such astronomical proportions all over the world. But it seems that we have as a society finally accepted that people must have their right to housing secured. This problem will not go away on its own and we must act collectively and intelligently. Most importantly, the pandemic emphasized the importance of grassroot movements and organizations in order for public policy to reach the so-called "last mile".

Especially, in countries with very high inequality and large parts of the population in informality, public policy can gain scale but often not capillarity. This is many times the case in Brazil. Thus, it is crucial that space is made and resources are shared with grassroots and other civil society organizations that have been collecting, publishing and sharing data from "invisible" territories. Here we still have a long way to go, but grassroots organizations are proving time and time again they have the capacity to go, work and mobilize where governments can't. We need people and organizations that have the vision to work together in other to expand their reach and impact. Deep collaboration is the way forward.

Through our 25 years of practice, at TETO (TECHO), in Latin America (present in 18 countries), we have worked closely with leaders in informal settlements, and in the process of building with families over 131.000 homes, transformed not only ourselves but also our work methodology has evolved tremendously. This was only possible because of the deeply rooted way we connect, listen and work together. We have extended those connections to other organizations and in some countries managed to build bridges between communities and local and federal governments. This model is one I believe we need to explore and invest in, in order to build sustainable, healthy and just cities.

And lastly, we must come quickly to terms with the fact that there is no single magical solution for our health and housing crisis. We must come together to build on multiple levels a social pact between all stakeholders that entails collaboration, the sharing of power and resources, the voice and experience of people who are solely responsible for their built environment. This will take time and negotiation but it needs to be done. In the meantime, emergency solutions must be considered as people continue to live in vulnerability while medium and long term solutions are developed and built.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Net Zero · Public Governance

illuminem briefings

Public Governance · Ethical Governance

Charlene Norman

Sustainable Business · Sustainable Finance

The Guardian

Diversity & Inclusion · Public Governance

Sustainable Views

Corporate Sustainability · Human Rights

Deutsche Welle

Public Governance · Social Responsibility