Making temporary carbon dioxide removal permanent with horizontal stacking

· 9 min read

The carbon cycle: simply put, it is the exchange of carbon between biosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere and atmosphere. To remove carbon from the atmosphere, we have to store it in either bio-, litho- or hydrosphere. This implies that there are many forms of carbon dioxide removal (CDR). For companies, it is difficult to compare solutions and to decide which is the most impactful and the most cost-efficient solution that fits the corporate strategy. One key criterion to assess and compare solutions is “permanence”. However, the concept is flawed and poorly understood.

Most forms of carbon storage are not permanent. Carbon regulation has been unclear about “permanence” since the beginning. The 1998 Kyoto Protocol treaty established the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) without a definition of permanence. Similarly, the 2016 Paris Agreement did not define the term either. Unfortunately, this lack of clarity persists across today’s leading initiatives and frameworks. To illustrate, the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM), the Science-Based Targets (SBT), the Oxford Principles for Net-Zero Aligned Offsetting, and the EU's Carbon Removal Certification Framework (CRCF) do not clearly define permanence, nor do they specify how long a storage period should be to qualify as "permanent." As a result, there is a pressing need for further consensus and clarity on this very critical aspect of carbon accounting and CDR.

In today’s absence of a definition of “permanence”, practitioners mostly use the term to describe the duration of carbon storage. However, there is more to consider than arbitrary time horizons. There is an additional, more granular metric, namely the reversal risk of the storage form. In fact, the two distinctive “permanence” metrics are:

It is best to think of permanence as additionality delivered over time. So a high reversal risk contradicts additionality. Therefore, reversal risk is as important as storage time when assessing “permanence”. Reversal risk can be best described as the volatility of biosphere and lithosphere. This is why it is vital to distinguish between the duration of carbon storage and reversal risk. In consequence, “permanence” can be easily replaced with the following terms to increase transparency for decision-makers:

Today’s use of “permanence” conflates the two concepts of durability and reversal risk. As a consequence, reversal risk is neglected as most people contextualize “permanence” only with durability. Therefore, “permanence” is an inadequate criterion to assess CDR. Even worse, it does not allow for a granular assessment of distinctive CDR technologies, that differ greatly in durability and volatility.

The goal of CDR is to neutralize emissions. There exists a consensus that net-zero is only possible with CDR. In consequence, decision-makers are confronted with a massive availability gap. Today, lithosphere solutions like Direct Air Capture (DAC), with very high durability and very low volatility are expensive at >1000€ per ton. Less durable and high-volatility biosphere solutions like forestry CDR are available for a fraction of the price.

Given the urgency of the climate crisis, the monumental gap in CDR supply, and DAC’s limited cost-effectiveness, I argue that low-durability, high-volatility solutions should be part of the solution. The NGO Carbon Gap also states that “lower durability carbon removal still has substantial value”. Clearly the more durable a solution and the lower the volatility, the better.

So how can buyers compare CDR across time scales? Therefore, two key questions for buyers are:

For a removal strategy to work and to create powerful CDR portfolios, decision-makers have to compare solutions on key permanence metrics like durability and volatility.

In my view, the best way to do so is via the carbon accounting concept of horizontal stacking. Horizontal stacking aims to equate the durability and volatility of different CDR technologies. Most importantly, the concept alleviates the “permanence” concerns of temporary CDR. Bodie Cabiyo from Carbon Direct summarized the concept as:

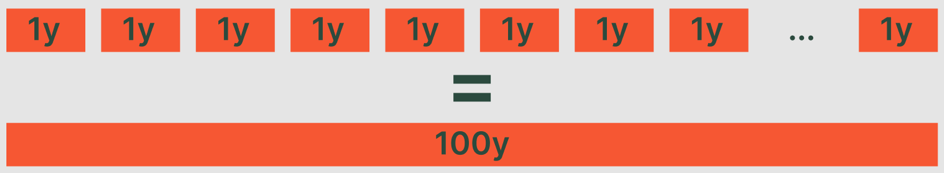

“Sequentially buying offsets as they expire to permanently offset a tonne of CO2. Firms seeking to neutralize their emissions in this way horizontally stack credits to create a continuous sequence of one tonne stored over time.”

To create durable climate impact, buyers constantly repurchase expired credits. A simple replacement rule is front and centre of the approach. If temporary CDR is not repurchased, credit after credit and year after year, emissions are only delayed.

Figure 1.

Source: author’s illustration

In essence, the concept rests on the premise that 100x temporary CDR credits with 1-year durability have the same durability as 1x 100-year CDR credit. It might seem inherently contradictory at first, but temporary CDR can in fact be procured in a highly durable manner.

To create climate impact with zero volatility, CDR has to be issued ex-post. This is possible as horizontal stacking slices up the crediting period in short e.g. 1-year increments. Ex-post issuance means after the crediting period is over and once the climate impact has been delivered. If CDR is continuously issued ex-post, the reversal risk is effectively zero from an accounting perspective. If droughts, wildfires or pest infestations affect a forest during the crediting period, credits are simply not issued. Volatility remains zero as buyers always repurchase the expired climate impact of the previous years. To sum up, in a horizontal stacking model, ex-post issuance means zero volatility.

Figure 2.

Source: author’s illustration

Historically, the concept traces back to 2006 and has its roots in the CDM. Yet it was only applied to afforestation and reforestation forestry compensation projects until 2012. But, given the critique of other accounting approaches, horizontal stacking gained more traction recently as illustrated below.

Although a nascent field of carbon accounting, horizontal stacking was discussed before. First of all, credits to the guys at Carbon Direct for establishing the concept. The NGO Carbon Gap introduces “contractual and physical permanence” as a fix to non(permanence). The folks at carbon ratings start-up Sylvera also conceptualize durability. And the Bellona Foundation gives policy recommendations to address differences in permanence here. MCC and PIK express the need and options for the regulation of CDR here (in German).

The think tank (carbon)plan analysed the costs of temporary carbon removal and developed a permanence calculator, which allows decision-makers to calculate the costs of replacing temporary CDR with permanent CDR. Robert Höglund gives a very clear account of the value and non-value of temporary carbon storage and provides a good overview of storage periods across solutions, while touching on reversal risk. Further, Robert discusses how permanent and temporary carbon storage can be compared.

The Carbon Business Council discussed horizontal stacking in its “Unlocking Carbon Dioxide Removal with Voluntary Carbon Markets” report. The OECD and the International Energy Agency highlighted the opportunities of temporary crediting to the UNFCCC back in 2001 titled “Forestry projects: permanence, credit accounting and lifetime”. Lastly, the World Bank discussed non-permanence crediting and the CDM’s tCERs in their review of their BioCarbon Fund.

This article adds to the field by making the case for horizontal stacking as a carbon accounting concept. It increases transparency and accountability of temporary CDR. More importantly, breaking down the arbitrary term “permanence” into durability and volatility, allows for adequate analysis and comparison of different CDR technologies.

To answer the initial question, horizontal stacking has two main benefits as it makes:

The key benefit, however, is that companies can start investing in negative emissions today via temporary CDR for a fraction of comparable costs, without having to compromise on durability and volatility. Along those lines, horizontal stacking allows for an interesting “bridge approach” strategy, in which temporary CDR is purchased today with a view to be replaced by other CDR technologies once they’re more cost-efficient.

Overall, aligning crediting periods across CDR technologies increases transparency for decision-makers. This helps CDR companies to sell and ultimately to scale. Increased accountability and one-year crediting periods also unlock new business models such as insurance. Insuring a 100-year forestry project is inherently unattractive from an insurer's perspective. Dividing it by 100, however, gives ample room for risk and insurance premium calculus. Functioning insurance mechanisms would drastically improve market conditions and growth opportunities.

Naturally, challenges remain. Most importantly, buyers bear the risk of finding replacement credits down the road. Also, if a company goes bankrupt or simply stops renewing, emissions are only delayed. On top, sellers bear comparatively high verification costs per ton as crediting periods are very short. I will discuss the challenges and solutions in a different article.

To sum up, the voluntary carbon market is begging for regulation and so is the nascent CDR space. Most importantly, the market needs a framework that goes beyond minimum requirements. In a new framework, horizontal stacking can solve the (non-)permanence issue of temporary CDR and increase transparency for buyers and accountability of sellers. To conclude, I argue that horizontal stacking is a viable approach to make CDR technologies comparable and unlock the value of temporary CDR.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Carbon Removal · Corporate Governance

illuminem briefings

Carbon Removal · Carbon

illuminem briefings

Carbon Removal · Net Zero

ESG News

Carbon Removal · Biodiversity

Carbon Herald

Carbon Removal · Corporate Governance

ESG Today

Carbon Removal · Sustainable Finance