· 4 min read

The Russia-Ukraine conflict is likely to have longer-term impacts on already volatile energy markets. According to a new report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, these impacts may prevent emerging markets in Asia from securing imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) supplies.

“There are numerous reasons that fossil fuel price volatility in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine may not be a short-term phenomenon,” says Energy Finance Analyst Sam Reynolds, author of the report.

“Lasting volatility in LNG prices could mean that price-sensitive buyers in Asia are effectively locked out of the market for several years, unable to compete on price. Ultimately, LNG import assets—terminals, pipelines, and power plants—face a high risk of being underutilized and stranded due to a lack of affordable fuel.”

Yet, many countries throughout Asia are doubling down on LNG import infrastructure projects despite the clear economic and financial risks. Nearly 80 million tons of LNG regasification capacity is aiming to come online in Asia over the next two years.

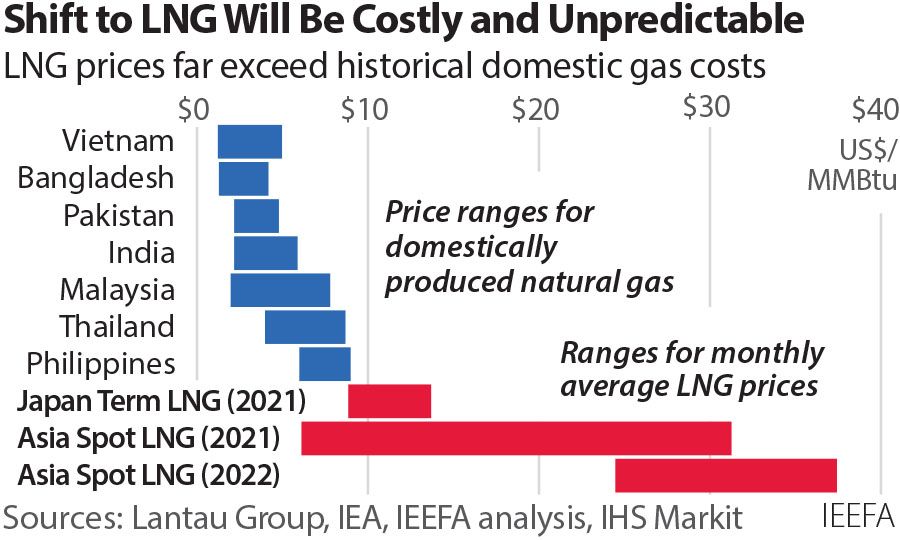

Several countries, including Thailand, the Philippines, and Bangladesh, have increased the targeted share of natural gas in their energy mixes despite declining domestic production. Prices of domestically produced gas in the region have typically ranged from US$1-5 per million British thermal units (MMBtu)—a far cry from the current LNG prices in Asia of US$35-40/MMBtu.

But with rapidly declining domestic natural gas reserves, many countries have looked to LNG as a convenient replacement.

“Rather than simply replacing one form of gas for another,” Reynolds says, “the shift to LNG will involve a steep, structural increase in fuel costs that may completely negate economic arguments for gas-fired power generation versus cleaner, domestically-sourced renewables.”

Multiple factors cloud the outlook for LNG prices over the next several years, meaning that volatility may continue to threaten price-sensitive buyers’ energy security and energy affordability.

For example, Europe has committed to weaning itself off Russian piped gas by procuring more LNG. This suggests an evolution from Europe’s role as a balancing buyer, which historically absorbed excess volumes, to a direct competitor with Asian customers.

Moreover, significant new LNG supply is not expected online until the middle of the decade. This means that Europe will have to pull cargoes from other regions—most likely from buyers unable to compete on price. Meanwhile, unplanned outages at existing LNG export facilities have increased every year since 2017.

The threat of reduced Russian energy supplies to Europe also looms large. Any cuts to the Russian supply of gas to Europe could push Europe further into LNG markets, tightening the demand-supply balance and boosting prices further.

The backdrop to these volatile prices is one of the most uncertain global macroeconomic environments in recent memory. Inflation was already at 40-year highs in many countries before the Russian invasion, and global debt skyrocketed in 2021 to its highest level ever.

“Such macroeconomic instability is likely to hinder countries’ ability to pay for higher-priced imported fuels and could mean longer-term volatility for LNG markets,” says Reynolds.

The report also notes that while long-term LNG purchase contracts may seem like a solution to shield buyers from volatility, there are important spillover impacts of fluctuating spot prices on term markets. High oil prices will also mean the cost of LNG under long-term, oil-linked contracts will rise.

Moreover, high spot prices can drag up the slopes of newly signed oil-linked contracts, locking in higher prices for buyers. The report finds that the pricing formulas of oil-linked contracts have tended to increase over the past two years of volatile LNG prices.

“Continued spot market volatility could likely encourage higher prices in new long-term contracts,” notes Reynolds.

Volatile spot market prices can also create a greater risk of legal disputes between parties to a long-term LNG purchase contract. When prices spike, sellers will see a greater incentive to minimize volumes delivered under long-term contracts to realize higher profits elsewhere.

In Pakistan, sellers have defaulted at least 11 times since LNG prices began to spike in mid-2020. For importers, these contractual disputes can have dire consequences on energy security and economic growth.

“For price-sensitive LNG buyers, now is not the time to build new LNG import facilities in Asia,” says Reynolds.

“Instead, countries can consider urgently revamping national energy priorities with an eye toward cheaper, more financially sustainable technologies that bolster energy sovereignty and self-sufficiency.

“Rather than doubling down on a bad hand, the goal should be to maximize renewable energy while minimizing the need for imported fossil fuels as a last resort.”

Read the report: Now is Not the Time to Build More LNG Import Terminals in Asia. Energy Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Energy & Sustainability writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.